eBook - ePub

Aesthetics

A Beginner's Guide

Charles Taliaferro

This is a test

Share book

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aesthetics

A Beginner's Guide

Charles Taliaferro

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Explaining what art is and what's not art. What is art? Why do we find some things beautiful but not others? Is it wrong to share MP3s? These are just some of the questions explored by aesthetics, the philosophy of art. In this sweeping introduction, Charles Taliaferro skilfully guides us through different theories of art and beauty, tackling issues such as who owns art and what happens when art and morality collide. From Plato on poetry to Ringo Starr on the drums, this is a perfect introductory text for anyone interested in the fascinating questions art can raise.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Aesthetics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Aesthetics by Charles Taliaferro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Theory & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art Theory & Criticism1

What is beauty?

While today beauty may seem an entirely subjective affair, there is a substantial historical tradition linking beauty and goodness. For the fourth-century BCE philosopher Plato, for example, beauty, truth, and goodness are foundational to a life worth living. To understand the appeal of this high, holistic view of beauty one needs to appreciate the contrast in the ancient world between the love of glory and the love of beauty. Let us take a look at an ancient Greek view of beauty and then see whether it has standing today.

Beauty versus glory

In Ancient Greece, one of the great themes in literature and culture was the pursuit of glory (kleos). In the earliest poem we have from this time, the Iliad, glory is to be found on the battlefield in aristocratic violence. Noble warriors like Achilles and Hector fight to the death and the one who is victorious receives glory in the form of a mixture of praise, awesome fear, and reputation. Glory, then, had a bloody dimension and was sometimes represented by a victorious warrior displaying the bloody armour or weapon or even the body of his defeated foe. Plato was not immune to this fascination with glory. But Plato and others sought to foster a different tradition, one that centered on beauty and fecundity rather than death and violent conflict. Instead of the primacy of loving Homeric kleos, Plato sought to promote the loving desire for the beautiful (kalon). In the place of the ideal soldier-warrior, Plato valorized the ideal, creative, ardent lover.

In the great fourth-century BCE dialogue the Symposium, Plato records a speech on love and beauty by the priestess and teacher of Socrates, Diotima of Mantinea. There is reason to believe Diotima was the name of an actual person as Plato seems to have rarely used names in his work that do not refer to actual people. If she was truly the source of the speech Plato records, Diotima is the most influential woman thinker in the world of ancient Greece and the history of what would come to be called aesthetics. Diotima teaches us that we should first appreciate particular beautiful things such as a specific beautiful body. We are then naturally led to love greater, more general beauties. When you love a woman or man, you come to realize that women and men are loveable or worthy of love. It is important to appreciate this is a movement or growing awareness from the particular to the general. It has been said of Don Juan, the fictional but legendary libertine, that he loved all women but loved no woman. Because he began and ended at the general level, he failed to understand what it is to love one woman. Diotima wants us to begin with a loving desire for a particular beauty and then ascend a ladder of loving desire until we come to what she called absolute beauty. She offers the following portrait of an initiation into the practice of loving beauty:

Well then, she began, the candidate for this initiation cannot, if his efforts are to be rewarded, begin too early to devote him to the beauties of the body. First of all, if his teacher instructs him as he should, he will fall in love with the beauty of one individual body, so that his passion may give life to noble discourse. Next he must consider how nearly related the beauty of any one body is to the beauty of any other, when he will see that if he is to devote himself to loveliness of form it will be absurd to deny that the beauty of each and every body is the same. Having reached this point, he must set himself to be the lover of every lovely body, and bring his passion for the one into due proportion by deeming it of little or of no importance.

We are to begin, then, in the material world, but this leads us gradually to even higher beauties. It is as though the experience of a specific individual beauty opens us up to an irresistible love of greater beauty. For those who think there is no necessity of going from the particular to the general, one might at least concede that there is some reason to do so. After all, in loving one person isn’t it natural or at least reasonable to love or at least appreciate and be grateful to the people and events that helped the person grow into your beloved? A climbing of the Platonic ladder involves growing out of one beauty and traveling upwards to a greater beauty. Arguably, such an expansion or growth may be understood in terms of taking pleasure in higher goods. It appears that when you love someone or something and you take pleasure in him or it, you do seem to expand your identity. To take a trivial example, if you take great pleasure in a sports team, you might well be able to use the possessive pronoun: Manchester United (or the Yankees or the Mets) is my team. Many of the ancient philosophers held that it is the very nature of pleasure to expand the soul and they likewise held it as the nature of pain or suffering to contract the soul (Sorabji 2000). Perhaps when one comes to love higher beauties, there is a sense in which these higher beauties become yours by delighting in them – even to the extent of garbing yourself in a team jersey that reads ‘Beckham’.

Diotima continues:

Next, he must grasp that the beauties of the body are as nothing to the beauties of the soul, so that wherever he meets with spiritual loveliness, even in the husk of an unlovely body, he will find it beautiful enough to fall in love with and to cherish – and beautiful enough to quicken in his heart a longing for such discourse as tends toward the building of a noble nature. And from this he will be led to contemplate the beauty of laws and institutions. And when he discovers how nearly every kind of beauty is akin to every other he will conclude that the beauty of the body is not, after all, of so great moment.

The ongoing ascent then involves an emancipating, ever-expanding philosophical, beautiful awareness of the nature of reality:

And next, his attention should be diverted from institutions to the sciences, so that he may know the beauty of every kind of knowledge. And thus, by scanning beauty’s wide horizon, he will be saved from a slavish and illiberal devotion to the individual loveliness of a single person, or a single institution. And, turning his eyes toward the open sea of beauty, he will find in such contemplation the seed of the most fruitful discourse and the loftiest thought, and reap a golden harvest of philosophy, until, confirmed and strengthened, he will come upon one single form of knowledge, the knowledge of the beauty I am about to speak of.

(Plato 1994, Symposium, 210a–e)

At the summit, the love naturally overflows with fecundity in which he or she gives birth to awesome creative productivity. The highest point of the beautiful involves a final transcendence of all images and the fulfillment of what Diotima describes as true virtue.

If someone got to see the Beautiful, absolute, pure, unmixed, not polluted by human flesh or colors or any other great nonsense of mortality . . . only then will it become possible for him to give birth not to images of virtue (because he’s in touch with no images), but to true virtue (because he is in touch with the true beauty).

(Plato 1994, Symposium 211e–212a)

This ascension to the beautiful, and thus to true virtue, as a process and consummation of true love, stands in dramatic contrast to the Homeric desire for worldly fame and domination on a battlefield. This is a heady, almost ecstatic account of a succession of loves and beauties that raise many questions we will come to shortly. But let’s first clarify Plato’s view of desire.

Plato (428–348 BCE) was a student of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle. He founded a school in Athens, the Academy, so named because it was in a garden named in honor of the Greek hero Academus. Much of Plato’s surviving work is in the form of dialogues and reflects Socrates’ recommendation that philosophy is best done in person in dialogue. Socrates thought that in dialogue one can more readily correct misunderstandings and take greater responsibility for one’s arguments than in writing, though ironically we would not know this about Socrates unless Plato or someone else wrote down Socrates’ opposition to writing. Throughout his work, Plato sought the essence of things, the essence of art and beauty, justice and truth, knowledge and the soul. Plato was opposed to Protagoras and others who promoted what Plato saw as an unacceptable relativism. In the dialogue Protagoras, Plato launched a major attack on relativist theories of truth (for example, what is true for one person may not be true for another). Plato thought that we should seek that which is permanently beautiful and not be bewitched by the flux and impermanence of the world. Platonic accounts of beauty had a major impact on late medieval Christianity and played into the celebration of beauty one finds in the Italian Renaissance. The fifteenth-century Florentine Academy was thoroughly Platonic in its teaching that true fulfillment can only be achieved through the love of beauty, truth, and goodness.

While Plato (perhaps inspired by Diotima) spoke of beauty itself, he also thought of beauty as the proper object of love. That which is beautiful is that which calls for or deserves our loving delight. Love, for Plato and many of the ancient Greeks, involves desire or eros (which may or may not involve what we would call the erotic). In the following myth or parable, love is pictured as the offspring of poros (the personification of plenty) and penia (the personification of poverty):

So because Eros is the son of Poros and Penia, his situation is in some such case as this. First of all, he is always poor; and he is far from being tender and beautiful, as the many believe, but is tough, squalid, shoeless, and homeless, always lying on the ground without a blanket or a bed, sleeping in doorways and along waysides in the open air; he has the nature of his mother, always dwelling with neediness. But in accordance with his father he plots to trap the beautiful and the good, and is courageous, stout, and keen, a skilled hunter, always weaving devices, desirous of practical wisdom and inventive, philosophizing through all his life, a skilled magician, druggist, sophist.

(Plato 1989, 203c–d)

Eros, then, is full of energy and stealth, and even inclined to philosophy (the love of wisdom) while also feeling need and a keen lack of satiation or fulfillment. There is a sense in which a person who desires is always seeking what the person lacks. If you are strong now, it makes no sense (from a Platonic point of view) for you to desire strength. It is because we lack beauty that we seek it. And in so doing, we take the first step in the direction of the beautiful itself. It is a deeply Platonic thesis that has been defended down to our own day, that if something is good, it is good to love it. There is a sense, then, that if you love beauty, your love in some sense is itself beautiful. If, for example, justice is both good and beautiful, it seems that loving justice would be both good and beautiful. We may imagine cases when someone may claim to love justice and do nothing to promote justice, but in cases where there is power and authenticity it appears that a lover of justice would naturally be one who would honor justice in her or his life and action. Platonists through the centuries have endorsed similar notions with respect to the virtues: to love wisdom is itself wise. As Plato suggests at the beginning of his masterpiece The Republic, the love of the good and the beautiful is an inherently youthful enterprise: it is not for those who are content with the loss of desire in old age, but for those at any age who are filled with a restless desire or eros for the good.

The legacy of Platonic beauty

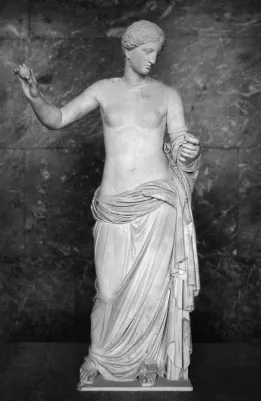

The Platonic philosophy of beauty has an important legacy from the ancient world through the medieval ages and early modern philosophy. It is often linked with works of art that represent the idealized beautiful body (as in Figure 1). Art that fosters the loving attention on a beautiful body can be seen as art that beckons us to get to the first rung on the ladder of love.

There is a natural sense in which when you love something, you are committed or at least inclined to think that objects resembling what you love are also worthy of love. It would be at least peculiar to love one woman and then not to believe that other women are worthy of love or loveable. It is difficult to imagine loving only a single object and not also loving its properties, properties that can be exemplified by others. Even if love of one person does not in fact lead you to love anyone or thing that resembles them, love of one person at least opens one up to understand the loveableness of others. It may be protested that human psychology is the reverse of Plato’s claim: we tend to move from the general (they are a nice bunch of people) to the particular (I love her or him). But there is evidence on the other side. For example, one of the reasons why most of us have heard of Confucius and few have heard of Mozi (two roughly contemporary Chinese thinkers) is because Confucius focused on specific relations and persons, whereas Mozi emphasized universal (general) love. There are many reasons for Confucius’ success in comparison with Mozi, but part of the difficulty with Moism is that its beautiful teaching was too abstract and not anchored in the particular and concrete. Or consider the concept of brotherly and sisterly love. Arguably, this general concept would not have any hold on us unless we have some acquaintance with concrete good cases of sibling relations. Once one grasps the goodness of the particular, however, one can then readily move to the more general.

Figure 1 Aphrodite of Arles, associated with Praxiteles (c.375–c.340 BCE), marble, Musée du Louvre (photo: Sting/Wikimedia Commons).

A look at beauty in other historical, cultural contexts offers some support for the Platonic notion of beauty and goodness. Plato and Diotima would resonate with the Hindu stress on the good, the true, and the beautiful. There is a familiar Hindu expression that describes God as Satyan (truth), Shivam (goodness) and Sundaram (beauty). Beauty, or Sundaram, coincides with the highest good and so there could not be something that was thoroughly beautiful and not good. African aesthetics also offers some support for a Platonic view of beauty and goodness. In Yoruba discourse, for example, ewa (the term most frequently translated as ‘beauty’) is directly linked with goodness. The Yoruba make a distinction between outward ewa and inward ewa. Outward ewa concerns physical appearance and behavior, whereas inner ewa is thought of as moral beauty. As Stephen David Ross observes, there is a widespread historical testimony to the link between beauty and goodness in many cultures. Ross offers this overview:

In the earliest cultures known, before written history, and in China, Egypt, the Islamic world, and sub-Saharan Africa, beauty was and still is a term of great esteem linking human beings and nature with artistic practices and works. Human beings – men and women – their bodies, characters, behaviors, and virtues are described as beautiful, together with artifacts, performances, and skills, and with natural creatures and things: animals, trees, and rock formations. In such cultures beauty, goodness, and truth are customarily related. Ancient Greece and China were no exceptions. In the Confucian tradition, Kongzi (sixth to fifth century BCE) emphasized social beauty, realized in art and other human activities. Two centuries later, Daoism united art and beauty with natural regularity and purpose, and with human freedom.

(Ross 1998, 237)

The Platonic link between beauty and goodness may seem deeply attractive in terms of value theory. In modern times, we perhaps often think that a villain is attractive or alluring, but this may be due to only a partial realization of the object in question. So, you might admire or find Satan fascinating in Milton’s Paradise Lost, but then there might be two things going on. What you admire truly is admirable. Imagine it is Satan’s defiance and independence that you admire. Such attributes may well indeed be valuable and beautiful. But then when you take seriously what Satan does in the poem it is hard to sustain the positive judgment. Sin emerges from Satan’s head in the form of a woman whom he then rapes. The child that is borne to Sin is called Death who then rapes its mother. When the details are worked out, there is no beauty here: taken on the whole, Milton’s Satan is pretty ugly. Consider an analogy. Imagine you observe an atomic explosion over a city. You see a huge mushroom cloud climb nine miles in the air. The cloud seems to you sensuous and billowy. Is this a major conflict that unsettles the Platonic account? Perhaps not, for you can see that the...