eBook - ePub

About Time

From Sun Dials to Quantum Clocks, How the Cosmos Shapes our Lives - And We Shape the Cosmos

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About Time

From Sun Dials to Quantum Clocks, How the Cosmos Shapes our Lives - And We Shape the Cosmos

About this book

From Stonehenge to beyond the Big Bang, an exhilarating scientific exploration of how we make time

From a Palaeolithic farmer living by the sun and stone plinths to the factory worker logging into an industrial punch clock to the modern manager enslaved to Outlook's 15-minute increments, our relationship with time has constantly evolved alongside our scientific understanding of the universe. And the latest advances in physics - string-theory branes, multiverses, "clockless" physics - are positioned to completely rewrite time in the coming years. Weaving cosmology with day-to-day chronicles and a lively wit, astrophysicist Adam Frank tells the dazzling story of humanity's invention of time and how we will experience it in the future.

From a Palaeolithic farmer living by the sun and stone plinths to the factory worker logging into an industrial punch clock to the modern manager enslaved to Outlook's 15-minute increments, our relationship with time has constantly evolved alongside our scientific understanding of the universe. And the latest advances in physics - string-theory branes, multiverses, "clockless" physics - are positioned to completely rewrite time in the coming years. Weaving cosmology with day-to-day chronicles and a lively wit, astrophysicist Adam Frank tells the dazzling story of humanity's invention of time and how we will experience it in the future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access About Time by Adam Frank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

World HistoryChapter 1

TALKING SKY, WORKING STONE AND LIVING FIELD

From Prehistory to the Agricultural Revolution

ABRI BLANCHARD, THE DORDOGNE, FRANCE • 20,000 BCE

The shaman stands before the opening of the cave and waits. Night is falling now and the piercing cold of autumn easily penetrates her animal-hide cloak. Outside, beyond the sheltering U-shaped bay of low cliff walls, the wind has picked up. These winds originated hundreds of miles to the north at the blue-white wall of glaciers that cover much of northern Europe.1

Winter is coming and the shaman’s people will have to move soon. The hides and supplies will be gathered and they will begin the trek towards the low-hanging sun and the warmer camps. But tonight the shaman’s mind is fixed on the present and she waits. It is her job to read the signs the living world provides. It is her job to know the turnings of Earth, animal and sky. The shaman’s people depend on this wisdom and so she waits to complete the task her mother suggested before she died. She waits, massaging the reindeer bone fragment in one hand and the pointed shard of flint in the other.

Now she sees it, the glow over the eastern horizon. The great mother rises. The shaman waits to see the moon’s face—pale, full of power. There, see! She is complete again.

From the crescent horns of many days ago, she has now returned, completed, to life. The full circle of the moon’s face, promising rebirth and renewal, has returned. The shaman holds the bone fragment before her in the grey light. With her index finger she traces out the long serpentine trail of her previous engravings on the bone. Then at the end of the trail she makes tonight’s mark with the flint-knife, carving the shape of tonight’s full moon into the hard bone.

Two rounds of the moon’s dying and rebirth have now been traced out. The shaman’s work is complete. The round of life and death in the sky, like the rounds of women’s bleeding, have been given form, remembered, noted and honoured. She returns the bone to its place beneath the rocks where she keeps the other shamanic tools her mother gave her so long ago. Now she has added to the store, a marking of passages, that she will use and pass on to her own children.2

WANDERING TIME: THE PALAEOLITHIC WORLD

The origins of human culture are saturated with time but we have only recently learned to see this truth. The evidence of the age when we grew into an awareness of ourselves, the cosmos and time itself had always been just out of reach. For most of our remembered history, the clues to the birth of culture and cultural time lay forgotten, buried a metre or so below the ground. Then, in the late 1870s, the discoveries began and we started to remember.

We first encountered the great awakening of our consciousness in 1879 in Spain when the nine-year-old daughter of amateur archaeologist Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola led him to a cave at Altamira. Venturing inside, he found its walls covered in vivid paintings now known to be twenty thousand years old. As archaeologists began systematic explorations, new caves were discovered, many of them also covered in paintings. The caves are a bestiary: bear, bison and mastodon appear on the walls along with other species. Sometimes these animals appear alone. Other times they are in herds. Sometimes we appear too—human figures set against the herd, spear at the ready.

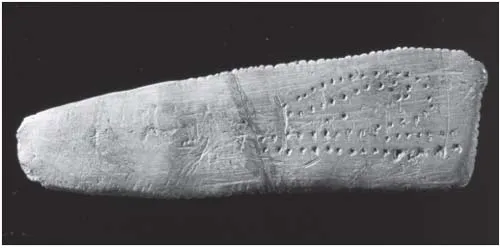

FIGURE 1.1. The Recognition of Time. The Abri Blanchard bone fragment (dating back between 12,000 to 20,000 BCE). Archaeologist Alexander Marshack proposed that the distinct pattern of engravings was an early record of lunar cycles.

These paintings gave voice to a heretofore silent past, showing that early humans were anything but “savages” incapable of representation, abstraction or response. This vivid prehistory, the time before written records, was set into a temporal sequence through painstaking work across the twentieth century. Radiocarbon dating allowed scientists to see when each cave was inhabited and when the paintings were laid down. As the sequence became complete, scientists came to understand how rapidly our ancestors had re-imagined what it meant to be human. With that recognition, conceptions of evolution and the origins of the human mind were thrown open. Scientists began searching for some purchase on a new theory that could explain how the mind rapidly woke to itself and to time.

Buried next to the painted walls, archaeologists discovered artefacts worked by human hands. There were statues of women with wide hips, pendulous breasts and finely articulated vulvas, seeming to focus on the mysteries of fertility. Spear points, needles, flint daggers and hammers spoke of cultures skilled in the creation of a diverse set of tools for diverse needs. And on the floor of a cave at Abri Blanchard, a rock shelter in the Dordogne region of central France,3 archaeologists found a “small flat ovoid piece of bone pockmarked with stokes and notches . . . just the right size to be held in the palm of the hand”.4

The Abri Blanchard artefact would sit in a French museum for decades until amateur archaeologist Alexander Marshack chanced upon it. Marshack was a journalist hired by NASA in 1962 to recount the long human journey leading up to the Apollo moon landing programme. In his efforts for NASA, Marshack dug so deeply into the history of astronomy, he found himself at the very dawn of human time. He first became obsessed with the Abri Blanchard bone when he encountered it, as part of his NASA project, in grainy illustrations of forgotten archaeology tracts. Eventually travelling to the imposing Musée des Antiquités Nationales near Paris, he found the small artefact all but ignored in a “musty . . . stone chamber” among “accumulations of Upper Palaeolithic materials, crowded under glass with their aged yellowing labels”.5

Marshack dedicated years of intense study to the Abri Blanchard bone fragment, rejecting the accepted wisdom that the notched carvings were nothing more than early artistic doodling. He traced over the curved trail of finely etched crescents and circles again and again. Finally he discovered a pattern echoing his own interests and his ongoing studies of the moon’s impact on human life, time and culture. In 1970 he published a closely reasoned and convincing argument that the etchings on the bone fragment were one of the earliest tallies of time’s passage, a two-month record of passing lunar phases.6 Rather than random doodles, the creator of the Abri Blanchard fragment had been marking time in a systematic way, for perhaps the first time ever.

In caves at other sites across the world, fragments of humanity’s first encounters with time were also found. Sticks with sequential notches, flat stones engraved with periodic engravings—each artefact gave testimony to an increasingly sophisticated temporal awareness.7 It was in those caves, tens of thousands of years ago, that the dawn of time broke in the human mind.8

Scientists call this era the Palaeolithic—meaning “old stone age”. The origins of human culture (and human time) occurred during the so-called Upper Palaeolithic, from roughly 43,000 to 10,000 BCE.9 All human beings during this period lived as hunter-gatherers and left us no written records of their thoughts (writing would have to wait until around 4000 BCE). Through painstaking analysis and considerable imagination, however, scientists have pieced together the outlines of the Palaeolithic human universe. Using the artefacts found at sites around the world and the narratives of contemporary hunter-gatherers, scientists have gained some understanding of these first modern humans.

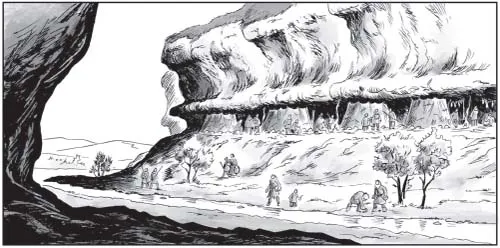

FIGURE 1.2. Artist’s depiction of Palaeolithic dwelling at cave formations in the Dordogne region where the Abri Blanchard bone was discovered.

The Abri Blanchard bone fragment dates back from twelve thousand to twenty thousand years ago, a time when the planet looked very different from the relatively warm, wet globe we now inhabit.10 It was an era when ice covered much of the northern hemisphere. France, as experienced by the unnamed palaeoastronomer marking the moon at Abri Blanchard, was a realm of polar deserts, tundra and towering glaciers.11 Humans were scarce on the ground, and they struggled to endure the hostile climate. This was not the first time members of the genus Homo had endured climate change of this kind. Ice sheets had come and gone in the past, but something remarkable happened to Homo sapiens during the planet’s last deep freeze that would, in time, alter the face of the planet itself.

Somehow the depths and deprivations of the last climatic winter drove our ancestors to make revolutionary leaps in behaviour. It was early in this period that human beings began burying their dead. Later they invented art and music. Clothes were soon fashioned by sewing animal pelts together.12 People began to invent systems for counting and, most important, started to codify the passage of time.13 It is in this period that the modern mind—with its penchant for analysis and allegory, concretizing and abstraction—emerged. Compared with earlier eras, the speed with which these radical changes swept through populations is startling and has led scholars to call the Upper Palaeolithic the Big Bang of consciousness.14 Any understanding of the inseparable narratives of cosmic and human time must begin here, with the rapid expansion of consciousness that would one day embrace the very cosmos in which it was born.

TIME OUT OF MIND: THE ORIGINS OF MODERN CONSCIOUSNESS

The explicit recognition and representation of nature’s repeating patterns were radical developments in hominid evolution. Thus, to understand the emergence of time in the mind, we must first understand the emergence of mind.

The hominid species that came before us faced challenges similar to those facing our ancestors. From the fossil record, it appears that the earliest versions of Homo sapiens may have overlapped for a brief time with both Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis.15 It is also clear that until a mere fifteen thousand years ago we were in direct competition with a group of hominids who were likely also the descendents of H. heidelbergensis, Homo neanderthalensis—the Neanderthals.16 This overlap with other species, particularly the Neanderthals whose brains were essentially the same relative size as ours, raises a pressing question: what spurred the Big Bang of consciousness in the Palaeolithic era?17

It wasn’t the environment that woke us up. In the long stretch of time before the Palaeolithic’s cognitive revolution, the same challenges presented themselves over and over. Ice sheets grew and ice sheets retreated. Early hominid species adapted by changing behaviours as the situation demanded. What was lacking, however, was rapid innovation and learning. The toolkit of the human species was impressive compared to that of nonhominid species: the domestication of fire, deliberately shaped stones for cutting and scraping.18 But the pace of innovation in the development of these tools and the mental processes likely used in their development seems positively glacial.

The basic stone tools our ancestors used 1.5 million years ago look fairly similar to those used by their descendants a million years later. Almost no technological innovation appears over the course of thousands of generations.19 On the other hand, comparing the brute stone scrapers used in 100,000 BCE to the needles, harpoons, arrow points and axes developed in 20,000 BCE is akin to comparing a raft to a nuclear submarine.

There are many competing theories for the rapid origin of the modern human mind. One of the most fruitful lines of research comes from evolutionary psychologists who, in the 1980s and 1990s, began thinking of the prehistoric mind as a kind of Swiss Army knife. From this perspective the mind is remarkably complex and does many highly specialized tasks that it can only have developed in response to very specific evolutionary pressures. Researchers Leda Cosmides and John Tooby have each argued that, like a Swiss Army knife, the mind has different blades—that is, different cognitive modules.20 Each module adapted in response to specific challenges our hunter-gatherer ancestors faced 100,000 years ago. These modules come with their own data and instruction sets—they are content-rich. A Homo sapien child born fifty thousand years ago (or fifty years ago, for that matter) already had modules for hunting, social interactions, tool building and so on. Thus, each module comes hardwired with a considerable storehouse of data.

There are compelling arguments supporting this claim. When a tiger leaps towards you from behind a rock, a mind built like a generalized computer sorting through all possible responses may not be the optimal evolutionary setup. A brain built like a Swiss Army knife, however, might very well provide the evolutionary adaptation to keep you alive. Given the notorious speed of hungry tigers, a Swiss Army knife mind with preloaded modules governing tiger recognition and the run-like-hell response would appear, on the face of things, to be a more successful evolutionary strategy.21

There is also compelling evidence for this type of hardwiring. According to some lines of research, we appear to be born with at least four distinct domains of intuitive knowledge. These content-rich modules govern language, human psychology, biology and physics. In each of these domains there is evidence that humans evolved with an internal guidebook of understanding, a degree of hardwiring imprinted by evolution, to help us deal quickly with communication, social interactions, the living environment and the behaviour of the material world.

Experiences of secondary school science lessons may convince many people that they have no intuitive understanding of physics. Psychologist Elizabeth Spelke would disagree. Along with researchers such as Renée Baillargeon and others, Spelke has explored the notion of a preexisting “folk physics” innate to us all. Spelke has shown that even very young children have a clear understanding of the behaviour of physical objects.22 Though children’s lives are built around (and depend on) interactions with other people, they can clearly distinguish the properties of people, other living things and inanimate objects. Most important, children seem to be born with concepts of solidity, gravity and inertia. From an evolutionary perspective, intuitive physics makes sense. From the flight of a projectile to the impact of two stones against each other, an intuitive grasp of physics serves as cognitive bedrock for learned skills such as tool making and weapon use.

While the Swiss Army knife story of the mind’s evolution is powerfully suggestive, it is likely not the whole story. Archaeologist Steven Mithen has argued that the “architecture” of the mind—its specific cognitive structure—had to evolve in specific ways to drive the Big Bang of consciousness. In particular, Mithen sees the ability to move information between modules as the innovation that led to the modern mind and the all-important capacity for culturally invented time. Moving information between modules allows for metaphor and analogy, which are the essence of human creativity. When information is shared between modules, a lump of clay that is roughly in the shape of a human form becomes the spirit of a departed ancestor, some coloured fluid splashed on a wall becomes a symbol for a bull felled in a fierce hunt, and markings engraved on a bone become a record of the moon’s phases.

Mithen likens the developing mind to a building with different rooms, each housing a different cognitive module. The story of the mind’s evolution is a narrative of reworking its architecture. Only when the architectural plan of the human mind changed by removing walls between isolated modules could the rapid evolution of consciousness and culture begin. As Mithen puts it, “In the [modern] mental architecture thoughts and knowledge generated by specialized intelligence can now flow freely around the mind . . . when thoughts originating in different domains can engage together, the result is an almost limitless capacity for imagination.”23

This new architecture of mind did not, of course, emerge on its own. The fact that evolution instilled in us an intuitive physics means that one cannot ignore the physical ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Contents

- Prologue: Beginnings and Endings

- CHAPTER ONE

- CHAPTER TWO

- CHAPTER THREE

- CHAPTER FOUR

- CHAPTER FIVE

- CHAPTER SIX

- CHAPTER SEVEN

- CHAPTER EIGHT

- CHAPTER NINE

- CHAPTER TEN

- CHAPTER ELEVEN

- CHAPTER TWELVE

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Illustration Credits

- Index

- About the Author