- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

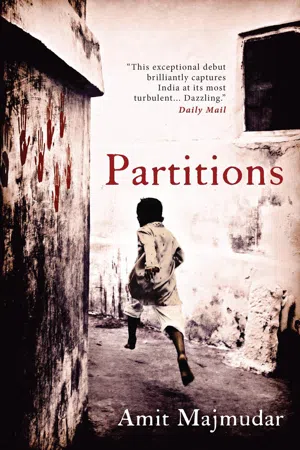

Partitions

About this book

As India is rent overnight into two nations, sectarian violence explodes on both sides of the new border, with tidal waves of refugees fleeing the blood and chaos. Fighting to board the last train to Delhi, Shankar and Keshav, six-year-old Hindu twins, lose sight of their mother and plunge into the whirling human mass to find her. A young Sikh woman, Simran Kaur, flees her father, who would rather poison his daughter than see her defiled. And Ibrahim Masud, an elderly Muslim doctor driven from the town of his birth, limps towards the new Muslim state of Pakistan.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

• Five •

Arrivals

Masud wakes up on the cart and squints into the late-morning light, his back aching and half his face finely printed by the leather of his black bag. At some point in the night, he shifted it from belly level, where Billi had nestled it, to under his cheek. Yesterday’s interrupted shave has given his face a split shading, dark scruff on one side, darker beard on the other. Now, on his paler side, this network of intricate lines seems to have aged him more swiftly.

A bewildered glance infers nothing from his driver’s back. The small body, wrapped in a white sheet, seems shaped like a woman’s, and he assumes she is sleeping. The only things that reassure him are the strays, who aren’t alarmed. None of them are looking his way. One, low to the ground, trails an olfactory hunch off the road. Masud scoots off and lets the cart go on without him. The farmer senses the cart shake and lighten, and he looks over his shoulder to make sure nothing has fallen. He sees the doctor standing in the road, dogs calmly sniffing circles around him, and he raises a hand. Masud, still uncertain what has happened, raises his hand in answer.

He doesn’t know it, but he is almost at the border. Only two hours, at his rate of walking, from the closest camp. He never knows when he crosses the border. It is too early in the border’s life cycle: it hasn’t budded checkpoints and manned booths yet, hasn’t sprouted its barbed-wire thorns.

He could get to the camp before noon, if all he does is walk. Lucky and Rimzim, who have kept up with the cart on foot all night, come running with summaries of the cases up the road. Two hours stretch to four. They have picked up the skills quickly, having attended dozens of examinations the prior day; Masud’s questions, around the adult patients, were often posed directly to them. So they collect the information they know he will need, where is the pain, how long has it been going on, is it dull or sharp or throbbing. Or, as is more often the case, where did they cut you, when did they cut you, what did they cut you with. The first patient he treats that morning is Lucky. Spiral whip welts wrap his forearm like two snakes up a caduceus.

I follow Masud into the camp. Here, too, there is no physical boundary. No sign, no appreciable transition. It forms itself gradually, like a city approached from the countryside. First the outskirts. Huddles of people, human shanties. Then, as he walks further, he passes a gradual scatter of tents. Or not tents exactly, but staked and propped lengths of burlap or saree. Under that richly coloured shade, large-eyed hunted mammals cower and peer up at him. The tents get closer together, and then, by an orderly dereliction, corridors define themselves. He can look down them for hundreds of yards. He can stand at their intersections. Streets of a miniature city, complete with human sewage dropped as indifferently as cow dung. The camp. Pakistan.

His strays have dispersed—other dogs are already established here, the tripwires of their urine everywhere. Negotiations, alliances, skirmishes growl and yelp sporadically across the camp. These, too, are questions of borders, jurisdiction, rights of access.

The first voice Masud hears is that of a man named Maulana Ijaz. The maulana is dressed in austere white and a knit cap, a dramatic grey beard down his front. A metal trunk lies open at his feet. His eyes have rolled back, and his neck is tucked very low between his shoulders, while his face is turned directly to the sun. His hands betray his blindness as he lowers tentatively and flutters his fingers over the contents of a trunk. He brings up a small skull.

‘Look, O brothers,’ he says, ‘look!’ His whole body is stretched to get the skull as high as possible. He sways as one stalk, the skull a seed-pod he wants the winds to take. ‘This is what they are doing to us, to our sons! They know our boys will never lower their heads. They pull us into the street and say, “Spit on your Qur’an,” but we won’t do it. This child, he was a warrior to the end, and handsome, a Pathan boy, green eyes. A little man. You should have heard him shout. So this is what they did. This proud boy, ya Allah, if only they had taken my eyes before then, I wouldn’t have had to see it. Do you see, O Muslims? Do you see what Hindustan plans for our sons?’

Masud squints at the skull. There is something wrong with it. The back of the skull balloons out, and the eye sockets are too large. Masud angles his head, studying it.

The maulana hands the skull to the person nearest him, and it passes from hand to hand. He descends to his trunk again and this time comes up with a stack of six photographs, each in a plastic slipcover. ‘But it’s our daughters they have always been after. These pure girls had no one to protect them. Do not cover your eyes. Look. Look at what has been done to them.’ The photographs are handed off, too. ‘One look and pass them on, make sure everyone gets a chance to see,’ the maulana adds quietly, in his speaking voice. Now he switches back into his strident, public voice. ‘No one to protect them—but tell me, believers, do they have anyone to avenge them? What, will no one avenge them?’

He lowers his face from the sun. The crowd remains a silent semicircle. The skull makes it to Masud. The jaw is lost; he offers his flat palm, and the maxilla rests on it, top molars biting him. He holds it only for the time it takes to pass it to the man next to him. Long enough for him to be certain the skull is no human child’s. The maulana starts up again, his blind eyes tearing up, and Masud realizes there is sincerity here, in spite of the circus-crier shrillness and the exhortations that come now. Maybe the maulana doesn’t even know he shows his congregation—his audience—a monkey’s skull. Maybe he does.

Masud drifts away before the photographs make it to him. He has seen the bite marks up close. His scalpel, just the prior day, traced the abscessed letters where a man had knifed his name. The word split and oozed as Masud’s blade followed the previous blade’s track.

I know what bothers him about this, why he cannot bear the calls to vengeance, redemption, war: Masud can bear to see the suffering, but he cannot bear to see it presented. The maulana is recruiting. I see for the first time the young men behind him. Two Pathans. They have been taking the maulana around the camp, calling crowds together to watch his show. They have collected fighters to join up and ride out. They call themselves ‘ghazis’, frontier warriors, what the first Muslims called themselves when they galloped as far as Sindh. Masud doesn’t see the past and future around this display, but he senses as much, and he cannot tolerate a reason behind speaking or showing other than compassion. If the purpose were compassion, then even raising the skull could be justified, human or non-human or falsified out of plaster. Raise the skull with any other motive, and it becomes a sin.

He has turned from the crowd when two of the orphans find him. It is the first time they touch his hand.

‘We found a medical tent, doctor sahib.’

‘There’s an Angrezi doctor there, and two nurses.’

‘I need to see them,’ says Masud.

Rimzim leads the way, a few steps ahead, chest out like a bodyguard. Lucky holds Masud’s hand.

‘Where are the others?’ asks Masud.

‘Around,’ says Lucky. ‘Are you going to build a hospital here?’

‘I don’t know if I can do that.’

‘We can’t go back to your old hospital, right? It isn’t safe for us there. You will have to build one here, in Pakistan.’

‘This madness will end soon, boys. We will all go back home.’

Rimzim looks over his shoulder. ‘But if you go back, doctor sahib, won’t you have to treat everyone?’

‘Yes. I would.’

‘Everyone?’

‘Remember yesterday, when you said you wanted to be a doctor?’

‘I remember.’

‘That is what doctors do.’

‘I don’t want to be a doctor, then,’ Rimzim says, and waves his hand to dismiss the idea.

Lucky tugs Masud’s hand. ‘India has all the hospitals. Pakistan needs hospitals, right? Me and the other boys were thinking, we could help you build one. We could work there. We wouldn’t take a salary, at first. But we would build a separate quarters where we would sleep and live.’

‘I’m not working there if we’re letting Hindus come,’ insists Rimzim.

‘We’ll build it in Pakistan. This side of the border.’ Lucky looks up at Masud. ‘I can draw you the plans, if you like. I have them in my head.’

‘I’d like to see them, Lucky.’

They have brought him to the six large, military-style tents that serve as the centre of the camp. A jeep is parked nearby, but it’s uncertain how it got there, as no road seems to lead up to it. People, some seated, some standing, wait in long lines that wrap around the tent corners and intersect and lose coherence, merging with the formless crowds of the camp itself. Lucky kneels and traces a large rectangle in the dirt. Rimzim, for all his declarations, kneels too, interested in the blueprint the other boys have come up with and intending to make corrections to it. He also intends to keep the crowds from treading on their work. ‘We’ll have it ready when you come back,’ Lucky promises.

Masud nods and approaches the red cross over the main tent. He is gazing out at the line when an English doctor in a pink-flecked white apron shoulders through the flap. He is towelling his hands and forearms, and he stops short on seeing Masud’s black bag and European-style clothes, however filthy.

‘Hello there,’ he says. Masud turns. ‘We weren’t expecting a volunteer. Dr Alan Rutherford.’

Masud wipes his dirty right hand on his dirtier trouser leg and shakes the hand offered him. He is reminded of his medical student days, his professors, the contemptuous eye-rolling of his British classmates whenever he presented cases. The stammer, which had eased around the orphans, pinches his tongue and won’t let go. He remembers the cards in his black bag. Rutherford takes one.

‘ “Dr Ibrahim Masud,” ’ he reads, the last syllable dwelled on for an extra second. ‘ “Paediatrics. Royal College.” Class of ’31, myself. We don’t have a paediatrician here in the camp. Heaven knows we could use one. But if you need to rest beforehand . . . Have you come from far?’

‘Out th-there,’ says Masud, pointing.

‘Have you worked at any of the other camps yet?’

‘Out there,’ Masud repeats. He raises his bag. ‘I . . . I work.’

Rutherford shades his eyes. ‘Out there? Do you mean the refugee columns?’

Masud nods.

‘That’s . . . that’s incredibly brave of you, Dr Masud, but . . . but there’s no need to have taken such a risk. If you wish to help, I can set you up here. There’s plenty of work. We’re getting more supplies driven down from Lahore this afternoon.’

Masud nods again. Rutherford eyes him. He wonders if Masud has been roughed up somehow while out caring for people in the column. Every one of his patients has stories of snatchings and stabbings, and not just at night. Rutherford is a selfless man, well into his second decade in India, for six of those years field surgeon to a Gurkha regiment; but for all his skill shooting a pistol on a range, and a build suited to the army, he is terrified to venture upstream into the kafila. Not without an armed escort, a convoy preferably, men in uniform with rifles over their shoulders. Enough bang and whizz to scatter the mobs. Selfless though his actions are, in his heart the barrier has not yet come down. He isn’t part of the crowd he treats. He perceives himself as the refugees perceive him: the white British doctor, six foot four, tall enough to see the top of every head in his vicinity. Here to help. Here to suture and dress the crude things these people have done to each other with their daggers and scythes. His compassion is genuine, but so is his remove. His concern for Masud is genuine, too, when he says, ‘You’re welcome to rest until then.’

Masud nods as Rutherford waves in his next patient and reenters the tent. I can see the restlessness that underlies Masud’s stare. These are the people who made it across, he is thinking. These are the ones who have already survived. The ones out there, though . . .

Part of me stays beside Masud and keeps watch, but I have gone from the wind at his ear to a whisper.

First I whisk north, then north-west. Villages pass under me. The occasional column of smoke dimples inwards, and the swirls take on the shapes of my thoughts. I make out two boys holding each other: Shankar and Keshav, in a gravel ditch beside the train tracks. I see how Keshav slept, cheek on Shankar’s shoulder, while Shankar shifted endlessly, forcing his panicked eyes shut but getting at best five or ten minutes’ rest at a time. He spent the whole night in this slow suffocation. The image spreads into formless smoke.

I keep going. At a certain altitude I can sense the earth curve in every direction away from me. During my early wanderings, in those weeks right after I left my feverish cot, I feared I would leave the earth entirely, its gravity not strong enough to hold me in orbit. I feared I would be flung into the darkness that hides behind the brightest daylight. The sky, I realized, was just a partition between the world and an emptiness, an illusion put there to let us go about our work. The blue sky all this time no better than a painted ceiling. I felt the urge, too, to seep out of myself, dilute to nothing, my consciousness a colourless, odourless gas, undetectable.

I don’t feel that now, though. I have never been so alive to the world, not even when I lived; never so close to the world, not even when I was in it. So I can go this high and dive at will, this time to Ayub’s truck rattling down a country road, a quarter-mile from the kafila it tracks. I sit on the cabin and look down. Simran sits close to Aisha, wrists and ankles bound. She doesn’t know her as Aisha, of course. To Simran, she is Kusum, stolen from her family in Sheikupura five days ago. For a time during the night, Simran had her cheek on Aisha’s shoulder, the same way Keshav did on Shankar’s. Only Aisha, too, was sleeping. When she woke up and saw Simran there, she moved her shoulder away, not wanting this intimacy, not wanting the responsibility that came with having protected her. The face with its small, girl features dropped and caught itself. Simran’s eyes struggled open, drugged as though with opium, and she didn’t seem to understand the rejection. Only after two straight hours of soft crying had she been able to sleep at all. She stayed awake until dawn and past dawn, terrified just by the proximity of Ayub sprawled lengthwise at the far end of the flatbed.

Qasim and Saif had smirked at him when he parked the truck and told them he was going in the back to sleep. He actually paused to speak as he pocketed the keys. ‘Why are you smiling?’

‘Save a little for us,’ said Qasim.

‘I’m going back there,’ Ayub shot back, ‘to protect my investment.’ He used the English word. To his ear, the word made him sound shrewd, self-possessed, cold—above the itch and small heat that agitated men like Qasim and Saif.

Aisha had sensed that in him perfectly, knowing men as well as she did. Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, she had seen them all, and they were more alike than they thought. She knew how the feeling of power made the sensation of pleasure possible for them. So when she saw Ayub raising Simran off the ground, and the other two approaching, the skinny one biting his thumbnail in uneasy fascination, she knew what to say to Ayub. Two sentences, almost a riddle, in brusque, brash, village-girl Urdu. ‘Don’t let them bite the apple you mean to sell, Ayub mian. No one’s that hungry.’

Don’t let them: She implied he was the calculating leader who had to keep the wild other ones in check. By denying Saif and Qasim—and himself—Ayub would exert more power than by forcing Simran. Referring to Simran as an item to be sold made him realize how much more this piece would sell for, intact. None of this was communicated directly. A push from Aisha would have made him push back. Immediately after her comment, she yawned and withdrew—a show of indifference so he wouldn’t think she was trying to work her own will.

Ayub looked at Aisha and then back at Simran, still not lowering her. One of Simran’s hands shot up to the roots of her hair and back over her chest again, unable to decide on the greater emergency. The pain, or the shame.

Qasim adjusted himself with a finger and spat to the side. ‘I’m second.’

Ayub glanced his way in irritation.

Saif made it worse, hand digging in his kameez pocket. ‘I have a coin.’

Ayub turned to Saif and gave ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- One Connections

- Two Departures

- Three Dispersal

- Four Convergence

- Five Arrivals

- Six Settlements

- Acknowledgements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Partitions by Amit Majmudar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.