- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

'Abd al-Malik

About this book

'Abd al-Malik, who came to promience during the second civil war of early Islam, ruled the Islamic empire from 692 until 705. Not only did he successfully suppress rebellion within the Muslim world and expand its frontiers, but in many respects he founded the empire itself. By about 700, the forms of a new realm which stretched from North Africa in the west to Iran in the east had taken clear shape with 'Abd al-Malik at its head.

This book covers the beginnings and rise to power of this immensely influential caliph, as well as his religious policies and innovations, (including the Dome of the Rock, the oldest surviving monumental building erected by the Muslims), his fiscal, administrative and military reforms, and finally, his legacy for later Muslims.

This book covers the beginnings and rise to power of this immensely influential caliph, as well as his religious policies and innovations, (including the Dome of the Rock, the oldest surviving monumental building erected by the Muslims), his fiscal, administrative and military reforms, and finally, his legacy for later Muslims.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Theologie & ReligionSubtopic

Asiatische Religionen

‘ABD AL-MALIK AND THE MARWANIDS

Muhammad b. ‘Abd Allah was born in the western Arabian town of Mecca in about 570, and there, perhaps first in 610, he began to receive revelations from God, who was telling him to preach monotheism to the pagan Arabs. In the end, the message did not go down well in Mecca, and within a decade the town’s polytheist establishment had forced him to flee to the neighbouring town of Yathrib, where he had much more success. Indeed, history was on his side. From there – the “Prophet’s city” or “Medina,” as it came to be known – he carried out a series of raids and battles that expanded his authority over much of the Arabian Peninsula, including the conquest of Mecca in 629 or 630. In 632 he died suddenly in Medina, which he had made the capital of his small polity.

In his time Muhammad was charismatic, persuasive, pragmatic and principled; he commanded respect and inspired followers. And after his death he continued to exert enormous authority over how Muslims saw the world and themselves – so much so, that by the ninth century his conduct had come to function paradigmatically for the law. For Muslims of that and subsequent periods, the law consisted of what God had said in the text assembled out of His revelations to Muhammad (the Qur’an) and what Muhammad had said and done as recorded in collections of Traditions (the hadith) – tens of thousands of them. How does one effect a marriage contract? How much does a daughter inherit? Who is subject to taxation? How does one pray? Answers could be found in Prophetic Traditions. Now there is little clear evidence that the first generations of Muslims thought that the law had to be based on Prophetic Traditions or that these Traditions existed in any number, but it is impossible to imagine a variety of Islamic belief in any period that was not informed in one way or another by a memory of who Muhammad was and what he had done.

This was certainly the case for seventh- and eighth-century Muslims – and not just because the memory of the Prophet was still fresh for them. It was also because seventh-century history was so contentious and the stakes so high. For Muhammad had made some steep demands on behalf of God, and he succeeded only in the face of some very fierce opposition, first within Mecca and, after his emigration to Medina, outside of it too. In later centuries, conquest generally led only indirectly to conversion, with the result that most Islamic states through the tenth and eleventh centuries governed large (and frequently majority) non-Muslim populations. But the demands were greater early on, when Muhammad was preaching amongst the pagan Arabs of the Peninsula. Muhammad may frequently have been diplomatic, but his message of radical monotheism was uncompromising: he insisted on nothing less than obedience to God, and what this meant in practice was declaring God’s oneness, acknowledging his prophecy, and signalling this acknowledgment by paying a tribute of one kind or another to him or one of his representatives. (This distinction between the fate of the pagan Arabs of the Peninsula, for whom conversion was required, and that of non-Arabs outside of it, for whom it was not, came to be expressed in a Prophetic Tradition that “No two religions shall meet in the Arabian Peninsula” – a good example of the Prophet being made to articulate the law.)

Conversion to Islam was thus an expression of belief and an act of politics. Some tribesmen had the very good sense to ally themselves with Muhammad and his movement early on; others did not. But whatever the individual circumstances – and these could vary greatly, with some individuals coming into fantastic wealth, others into ignominious disgrace – the decision had lasting consequences. For the speed and enthusiasm with which one converted to Islam, in addition to one’s subsequent conduct alongside and after Muhammad, went a long way towards determining the social status one’s descendants would enjoy in early Islamic society. Simply put, the earlier and more committed the conversion, and the more one’s forebears distinguished themselves in the cause of Islam, the better. Those who had converted in Mecca and joined Muhammad in Medina were called the “Emigrants” (muhajirun), and those who converted in Medina, the “Helpers” (ansar); the words are capitalized because they are technical terms that denoted high-status Muslims, this status being inheritable. Military service, which meant hazarding all on behalf of Islam, was similarly influenced by this idea of “precedence:” those who joined conquest armies early on were paid at higher rates than those who joined later, and their descendants would continue to claim the privilege. Little social status now attaches to membership in the “Daughters of the American Revolution,” at least outside of 200,000 women who claim direct descent from those who aided or served in the American Revolution; much more attached to early Muslims who could claim to descend from distinguished participants in Islam’s founding moments.

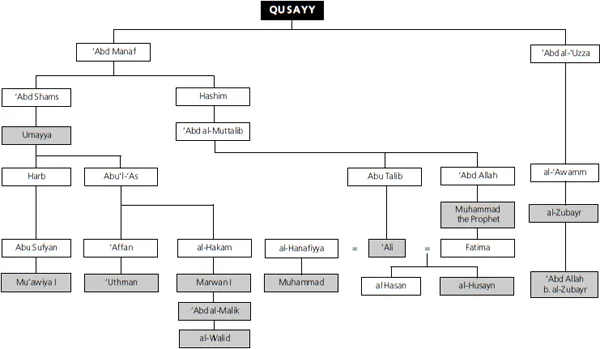

An apposite example of a high-status Muslim of the seventh century is a figure named Ibn al-Zubayr, about whom much more will be said in the next chapter. Like ‘Abd al-Malik and Muhammad himself, Ibn al-Zubayr was a member of the Quraysh, the leading tribe of seventh-century Mecca, and the tribe from which all caliphs were to be drawn. Because tribes were large, effective kinship groups were actually smaller sub-lineages, which can be called clans; whereas Muhammad belonged to the clan of the Hashim and ‘Abd al-Malik to the Umayyad clan, Ibn al-Zubayr belonged to the ‘Abd al-‘Uzza clan. As a member of the Quraysh, Ibn al-Zubayr thus enjoyed a very advantageous tribal affiliation.

Even so, there were lots of Qurashis, and what made Ibn al-Zubayr special were his flawless credentials as an early and committed Muslim. Ibn al-Zubayr had had the great fortune to have been born in about 624, some eight years before Muhammad’s death. The timing was doubly significant. First, he could be counted amongst those old enough to remember Muhammad’s words and deeds. He was thus a Companion of the Prophet, and although we cannot be sure if this term was in operation in this sense in the seventh century, we can still be sure that having direct memory of Muhammad meant a great deal. Just as there were lots of Qurashis, so were there lots of Companions, however, and this takes us to the second respect in which the timing of Ibn al-Zubayr’s birth was significant. Just as the first caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632–4) was reckoned by many to have been the first male to convert to Islam, so was Ibn al-Zubayr often considered to have been the first child born to the Emigrants. In other words, he enjoyed pride of place in that first generation of Muslims who were born under the new dispensation. As a young man, he is also said to have campaigned in Syria, participating in the early and pivotal battle at Yarmuk (636), where a Byzantine army was routed.

Ibn al-Zubayr thus had timing going for him. He had something more. He had been born to al-Zubayr, who was one of the Prophet’s closest Companions, and to Asma’, who was a daughter of none other than the caliph-to-be Abu Bakr, and a sister of ‘A’isha, one of Muhammad’s leading wives. The connection between Ibn al-Zubayr’s family and ‘A’isha was political as well as familial. Al-Zubayr had joined ‘A’isha in leading a rebellion against ‘Uthman, the third (and first unpopular) caliph. In fact, Ibn al-Zubayr himself participated in that rebellion, which, though unsuccessful in the end, enjoyed wide support. He later returned to Medina, where he spent the next twenty-odd years in disdainful opposition to the rule of Mu‘awiya (‘Uthman’s successor), before making a claim to the caliphate during the Second Civil War. In sum, propitious timing and favorable circumstances of birth, followed up by political acuity, made for an imposing combination: Ibn al-Zubayr was a paragon of early Islamic belief and action.

The Quraysh (principal figures are shaded).

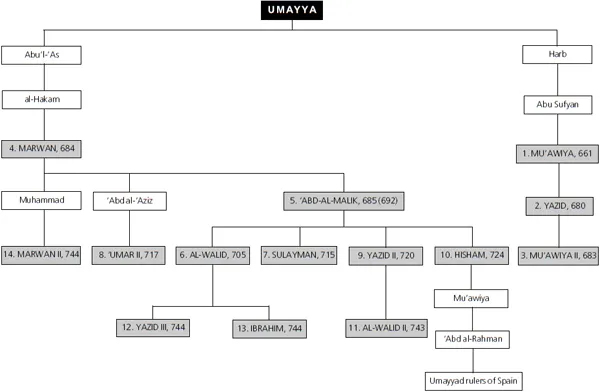

The Umayyads (caliphs shaded).

Comparing ‘Abd al-Malik’s background with that of Ibn al-Zubayr is instructive because the latter, though highly credentialed in Islamic terms, was in the end a political dead end. Both were members of the Quraysh, but ‘Abd al-Malik came from the Umayyad clan, which was very powerful on the eve of Islam. Indeed, it was precisely their prestige and power that explained the Umayyads’ initial resistance to Muhammad and his ideas. (Above I wrote that precedence went “a long way” towards determining social status in early Islam; it did not go all the way because pre-Islamic ideas of kinship – belonging to higher or lower prestige tribal lineages – also continued to matter a great deal in early Islam.) And compared to Ibn al-Zubayr’s, ‘Abd al-Malik’s credentials as a Muslim were weak.

Whereas Ibn al-Zubayr’s father embraced Islam, ‘Abd al-Malik’s forefathers opposed it. His maternal grandfather, Mu‘awiya b. Mughira, was apparently executed for his opposition to Muhammad, while others were sent into exile; such was the case of al-Hakam, his paternal grandfather, who only converted when Mecca fell to Muhammad, and perhaps also Marwan, ‘Abd al-Malik’s father, who would be known as “exiled son of an exile.” Whereas Ibn al-Zubayr was a Companion of the Prophet, ‘Abd al-Malik himself was born in Medina twenty-five or twenty-six years after the Hijra (there are conflicting reports), and he could claim none of the status that came with having known the Prophet or having participated in the early and glorious conquests. As a fifteenth-century historian puts it, “If one holds the opinion that precedence of conversion to Islam is the sole factor conferring a right to the caliphate, then the Banu Umayya (the Umayyads) have no recorded ancient claim of conversion and no participation in any celebrated battle of early Islam to their credit” (al-Maqrizi, 43). Finally, whereas Ibn al-Zubayr was associated from an early age with pious opposition against what came to be regarded as iniquitous Sufyanid rule, ‘Abd al-Malik was complicit in it. We read that at the age of ten, ‘Abd al-Malik was by the side of the first Sufyanid caliph, ‘Uthman, when he was murdered by rebels.

That ‘Abd al-Malik overcame these disadvantages says something about his and his family’s determination and resourcefulness. What follows tries to explain both.

THE MARWANID BACKGROUND

Early Islamic politics and institutions were conditioned by kinship ties – ties through blood, marriage and adoption – that made individuals into members of families, clans and tribes; they were especially so in the first century, when tribalism remained potent amongst the conquering Arabs. To convert to Islam initially required joining an Arab tribe; which conquest army one joined and where in a garrison city one settled depended to a large degree on one’s tribe; the office of the caliphate itself was held only by members of the Quraysh tribe. In general, the smaller the lineage unit, the stronger the ties, so the bonds of families were stronger than those of clans, and those of clans stronger than tribes. (Disputes amongst the tribe of the Quraysh were the rule of early Islamic politics; but these were altogether less frequent within its Sufyanid and Marwanid clans, these being altogether smaller.) Tribesmen could lose contact with each other through settlement and migration, the result being the erosion or complete loss of that sense of belonging; but members of the same family, even if a large one, had a stronger sense of belonging. Knowing each other much better, they usually worked much harder on each other’s behalf.

Little wonder then that although the Prophet’s first successors were chosen by acclamation and election, it took no more than four caliphs for the principle of hereditary succession to establish itself, with Mu‘awiya’s appointment of his son Yazid. Fathers were almost always followed to the throne by sons, but there were occasional exceptions. Mu‘awiya would be succeeded as caliph by a son and grandson. ‘Abd al-Malik would succeed his father, Marwan, as caliph, but we shall see that there was some controversy about this (it seems that Marwan himself had stipulated that a second son, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, should succeed ‘Abd al-Malik, but since ‘Abd al-‘Aziz predeceased ‘Abd al-Malik, the way was cleared for the latter to appoint his own son, al-Walid). ‘Abd al-Malik would be succeeded by no fewer than four sons.

So kinship was important. So, too, were large families. In the pre-modern Middle East, large families functioned as signs of status and wealth, as hedges against the perils of life, and as currency for polit-ical exchange through intermarriage. The larger the family, the better. ‘Abd al-Malik’s was big, but not exceptionally so by the standards of the day. By one reckoning, his grandfather al-Hakam fathered twenty-one sons and eight girls, and his father, Marwan, had some ten sons and two daughters. Children were produced not only by wives, who, during the course of a man’s life, often exceeded four in number (the maximum allowed at any one time by Islamic law), but also by concubines, whose children enjoyed full legal rights. (Muhammad b. al-Hanafiyya, an important figure of the Second Civil War, was a son of a concubine of ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law.) ‘Abd al-Malik was the issue of his father’s marriage with ‘A’isha b. Mu‘awiya b. al-Mughira, who was an Umayyad, but his father also forged marriage alliances with other tribes, such as the Kalb, who were especially important in the Umayyads’ home in Syria, as well as with descendants of ‘Ali. Of all of ‘Abd al-Malik’s siblings, it seems that he only had one full brother and sister of any note. According to our earliest biography, the caliph would himself father eighteen children by six wives and an unspecified number of concubines. (He is given to have had views on the respective virtues of different kinds of concubines: “He who wishes to take a slave girl for pleasure, let him take a Berber; he who wishes to take one to produce a child, let him take a Persian; and he who wishes to take one as a domestic servant, let him take a Byzantine”; al-Suyuti, 251). All of his marriages were in one way or another political, the most striking perhaps being his union with a daughter of ‘Ali, whose family would produce a long string of figures actively or passively opposed to Umayyad rule.

Of the circumstances of ‘Abd al-Malik’s birth and early childhood we know disappointingly little. The paucity of solid information has a double explanation. First, our sources reflect social attitudes that, unlike ours, did not hold childhood to be a formative influence upon the adult personality: this means that the early and private life of a caliph-to-be was neither remembered accurately nor transmitted carefully. Second, insofar as the Umayyads attracted any attention in the first half-century of Islam, it was the Sufyanid branch, which produced Mu‘awiya and his sons, that did so. During the reigns of Abu Bakr and ‘Umar, the Marwanids seem to have kept their heads low (here it must be recalled that theirs had been an inglorious reception of the Prophet’s message). The family’s fortunes changed when their kinsman ‘Uthman, who was to become notorious for his nepotism, became caliph in 644. It was ‘Uthman who seems to have rehabilitated his cousin Marwan, who had been disgraced by his late and opportunistic conversion, giving him a gift of some 100,000 silver coins; this nepotism extended to other members of the Marwanid house (including the father, al-Hakam). During ‘Uthman’s reign, Marwan campaigned in North Africa, where he took what must have been a large share of plunder. Later, during the reign of his kinsman Mu‘awiya, he would have the opportunity for further enrichment when he was appointed to provincial posts in Iran and Arabia, before serving as governor of Medina twice, first in the 660s and again in the mid 670s. At some point in this period the caliph granted him an estate of palm-groves in Fadak, a town that lay a two- or three-day journey from Medina. The spoils of war, the graft and gift that came with governorships, and land thus formed the basis of early Marwanid wealth.

Just as nepotism brought the Marwanids into service for the Sufyanids – and all the wealth that such service produced – so, too, did it bring ‘Abd al-Malik his first appointment. We read that already during the reign of ‘Uthman he had worked as a secretary (a term used here in the elevated sense of “secretary of state”) in his hometown of Medina, and his father would appoint him governor of the Arabian town of Hajar. At this point he was apparently still a teenager, an age that was precocious by modern western standards rather than medieval Islamic ones, since the age of majority was reached when a male could wield a sword in battle – usually about twelve or thirteen. Precisely this ‘Abd al-Malik did, leading an army of Medinese against the Byzantines at about the age of sixteen. (When a rebel took ‘Uthman to task for appointing “young men as governors,” he had appointments such as ‘Abd al-Malik’s in mind.) Little is known about ‘Abd al-Malik’s early adulthood, aside from the fact that he kept Medina as his base, frequenting, we are told, the learned men of the Prophet’s city. It is nearly universally asserted by our sources that he remained there until the Second Civil War, when the Medinese expelled the Umayyads from the city in 683. It is tempting to think that this experience embittered him; certainly his deputy al-Hajjaj would go out of his way to humiliate many Medinese after taking control of the city ten years later. At this point, with the confusing events of civil war now unfolding in Syria, Iraq and the Hijaz, ‘Abd al-Malik’s movements draw more attention and are thus better preserved by our sources, even if the events of the civil war remain somewhat confused.

THE END OF THE SUFYANIDS AND THE BEGINNING OF THE MARWANIDS

Much of the confusion about the Second Civil War concerns chronology. Some has been settled elsewhere; here a simple outline of the events will suffice.

We may begin by excerpting from an account written by an eighth-century bishop, which survives in much later sources (Hoyland, 647). It is not accurate in all the details, but because it was written by an outsider who could not be bothered with matters of detail, it has the virtue of clarity.

Yazid b. Mu‘awiya died. Mukhtar the deceiver had already appeared at Kufa, claiming he was a prophet. Since Yazid had no adult son to succeed him, the Arabs were in turmoil. Those in Medina and the East proclaimed ‘Abd Allah b. al-Zubayr; those in Damascus and Palestine remained loyal to the family of Mu‘awiya; in Syria and Phoenicia they followed Dahhak b. Qays, who came to Damascus and pretended to be fightin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

- Chronology

- INTRODUCTION: JERUSALEM IN 692

- 1 ‘ABD AL-MALIK AND THE MARWANIDS

- 2 THE CALIPHATE OF IBN AL-ZUBAYR

- 3 THE IMAGES OF ‘ABD AL-MALIK

- 4 ‘ABD AL-MALIK’S EMPIRE

- 5 ‘ABD AL-MALIK AS IMAM

- 6 ‘ABD AL-MALIK AND THE ISLAMIC STATE

- CONCLUSION: THE LEGACY OF ‘ABD AL-MALIK

- Further Reading

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access 'Abd al-Malik by Chase F. Robinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theologie & Religion & Asiatische Religionen. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.