- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Munch's The Scream. Van Gogh's Starry Night. Rodin's The Thinker. Monet’s water lilies. Constable's landscapes. The nineteenth-century gave us a wealth of artistic riches so memorable in their genius that we can picture many of them at an instant. However, at the time their avant-garde nature was the cause of much controversy.

Professor Laurie Schneider Adams brings vividly to life the paintings, sculpture, photography and architecture of the period vividly with her infectious enthusiasm for art and detailed explorations of individual works. Offering fascinating biographical details and the relevant social, political and cultural context, Adams provides the reader with an understanding of both how revolutionary the works were at the time and of their enduring appeal.

Professor Laurie Schneider Adams brings vividly to life the paintings, sculpture, photography and architecture of the period vividly with her infectious enthusiasm for art and detailed explorations of individual works. Offering fascinating biographical details and the relevant social, political and cultural context, Adams provides the reader with an understanding of both how revolutionary the works were at the time and of their enduring appeal.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nineteenth-Century Art by Laurie Schneider Adams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art General1

Neoclassicism

In 1738 near Naples, in southern Italy, workers laying foundations for a summer residence for the king of Naples discovered the ruins of the ancient Roman city of Pompeii, although the presence of an old city there had been known of since the end of the sixteenth century. That same year witnessed the beginning of excavations of the ruins of the nearby Roman town of Herculaneum. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE had buried both cities under layers of volcanic ash, making them time capsules that preserved a view of life in the ancient world. By 1748, excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum were well underway, sparking a new interest in antiquity, a vogue for archaeology – as seen in the Classical motifs characteristic of the English interior decoration of Robert Adam (1728–1792) – and the increasing popularity of books on Classical art. In 1765 Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s (1717–1768) Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture was translated from German into English and fueled the endeavor to recapture what the author considered to be the lost virility of ancient sculpture.

This burgeoning interest in ancient Rome – and eventually in Greek and Etruscan art and society – led to the emergence of a new style in the arts known as Neoclassical, literally “New Classical.” Alongside Romanticism, Neoclassicism was to be the major art movement of the early nineteenth century but, like Romanticism, it began during the previous century. The appeal of the style was its reaction against the frivolity of Rococo, which had been the prevailing style of eighteenth-century Europe and the Americas. Neoclassicism began as an expression of Enlightenment philosophy and the principles of democracy. Called the “True Style” in France, Neoclassicism provided a moral dimension to iconography and was inspired by a formal interest in the styles of ancient Greece and Rome. In painting and sculpture, Neoclassical artists preferred the clear edges, smooth paint handling, lifelike figures, and antique subject matter they saw in Roman art. In architecture, ancient Greek and Roman elements were revived. Such choices harked back to an age associated with more democratic societies – the Roman Republic and fifth-century BCE Athens – than the European monarchies. But despite having begun as a style of revolutionary sentiment – notably that of the French Revolution of 1789 – Neoclassicism became an imperial style under Napoleon. As such it was used to project his image as a legitimate ruler in the tradition of Roman emperors.

Architecture

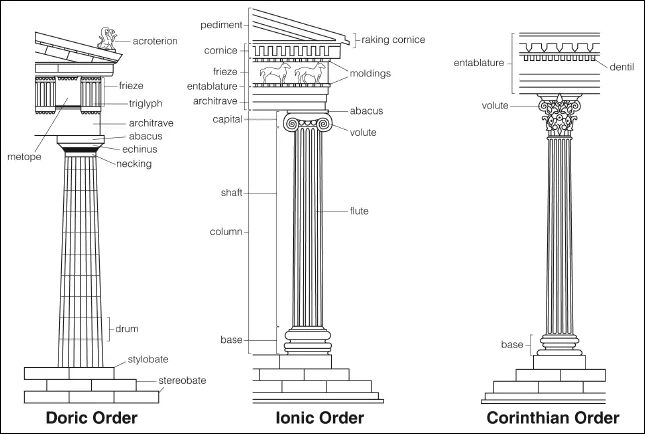

In England, the eighteenth-century architectural revival of antiquity began with Palladianism, which rejected the Rococo levity of the previous century in favor of more austere Classical forms. From 1725, Lord Burlington (1694–1753) began constructing Chiswick House (figure 1) on the outskirts of London. Intended as a place of relaxation and entertainment, Chiswick House was inspired by Andrea Palladio’s sixteenth-century Villa Rotonda in the northern Italian town of Vicenza. Burlington appropriated from Palladio the Greek portico, pedimented windows (surmounted here by a triangular element), a central dome, and a symmetrical façade. The columns on the portico are in the Corinthian order (figure 2), historically the latest and formally the most ornate of the three Greek orders (Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian) – types of architecture best distinguished by the forms and arrangement of their individual parts.

Figure 1 Richard Boyle (Earl of Burlington), Chiswick House, 1725–1729, London, UK. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In France and Germany, as in England, architects borrowed from the Greek orders to endow their buildings with a Classical flavor. The Paris church of Sainte-Geneviève (known as the Panthéon) was designed beginning in 1755 by Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713–1780), again in the Corinthian order. It is based on a Greek-cross plan, in which the four domed “arms” of the plan are of equal length and surround a larger dome at the center. The use of the Greek-cross plan here derives from the Renaissance notion that its architectural configuration expresses the ancient Greek belief in man’s centrality in the universe – that “man is the measure of all things.” An interior colonnade is repeated on the portico entrance, thus unifying the two areas of the church. By continuing the Corinthian entablature (see figure 2) around the entire building and placing a triangular pediment at the end of each cross arm, Soufflot created a unity of form that had characterized the Classical Greek style and had been revived by Italian Renaissance architects.

Figure 2 Labeled diagram of the three Greek orders: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.

In Berlin, from 1788 to 1791, Carl Langhans (1732–1808) built the Brandenburg Gate (figure 3) in the imposing Doric order, the earliest and sturdiest in appearance of the three Greek orders. Its overall design, flanked by smaller Doric porticos, peristyles, and fluted columns supporting an entablature surmounted by a narrow attic, is reminiscent of the Propylaea, the Classical entrance to the Acropolis in Athens. The Doric frieze (the horizontal section below the cornice) of the Brandenburg Gate is composed of alternating triglyphs and metopes, with a quadriga at the top. Like the Panthéon in Paris, the Brandenburg Gate was intended to evoke the grandeur of Greco-Roman antiquity.

Figure 3 Carl Gotthard Langhans, Brandenburg Gate, 1788–1791 (damaged during World War II and restored 2000–2002), Berlin, Germany. (Source: Thomas Wolf, www.foto-tw.de/Wikimedia Commons)

In North America, the Federal style, which was largely the invention of Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), was the equivalent of European Neoclassicism. Consistent with Jefferson’s interest in the architecture of Republican Rome – itself derived from Greek architecture – and his commitment to democracy, the Federal style departed from the Colonial Georgian style popular in the American South, which was named for the English king, George III. Like Lord Burlington in England, Jefferson had read Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture, which stimulated his study of Classically inspired buildings while he was ambassador to France. When, during the 1780s, Jefferson designed the Virginia State Capitol (figure 4), his model was the Roman temple with Corinthian columns known as the Maison Carrée, in Nîmes, in the south of France. Unlike the Maison Carrée, however, the Richmond Capitol is built in the graceful Ionic order, but it replicates the use of the portico at the entrance and the solid side walls. Whereas Roman temples typically stood on a podium, symbolizing the power of the emperor dominating the urban space before him, Jefferson situated the Capitol on a hill, accentuating the lofty dignity of the building. Here, the author of American democracy built a symbol of the power of citizens to govern themselves.

Figure 4 Thomas Jefferson, State Capitol, 1788, Richmond, Virginia. (Source: Jim Bowen/Wikimedia Commons)

Jacques-Louis David and Revolutionary France

In the eighteenth century, France was the intellectual and artistic leader of Western Europe. With the violent upheaval of the French Revolution in 1789, royal patronage began to decline. But, like the French kings, the revolutionaries recognized the importance of imagery for projecting their ideology and they used it accordingly. The most significant French painter to include revolutionary allusions in his work was Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825). David’s life and work mirrored the complex political situation in France before, during, and immediately after the 1789 Revolution. Born in 1748 in Paris, David grew up during the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI; he survived the Revolution and the period of the Napoleonic Empire (1804–1814), and died in 1825, during the Bourbon Restoration monarchy that lasted from 1814 to 1830.

While studying in Rome at the French Academy, David absorbed Neoclassical taste and developed an interest in ancient history and mythology. The widespread appeal of Classical subject matter in France was apparent in the continuing popularity of the seventeenth-century plays by Corneille and Racine. David shared the Enlightenment taste for combining antiquity with the present; the content of his paintings was often Classical, but at the same time directly linked to contemporary events. Diderot praised David’s work exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1781 as the embodiment of lofty Classical ideals.

CORNEILLE AND RACINE

The leading exponents of French Classical drama, Pierre Corneille (1606–1684) and Jean Racine (1639–1699), appealed to Neoclassical taste. Corneille published a series of plays based on ancient Greek and Roman themes. Among these were works inspired by the legends of Andromeda, Medea, and Oedipus. Corneille’s attraction to the theme of the power of reason over will is consistent with the ideals depicted in David’s Oath of the Horatii (figure 5). Many of Racine’s plays were tragedies based on Classical themes involving powerful female characters, such as Andromache and Phaedra, as well as those in Old Testament stories, notably Athaliah and Esther. His plays typically contained the Aristotelian theme of a hero or heroine, typically of noble blood, ruined by a character flaw. Known for the simplicity of his plots and the elegance of his language, Racine’s reputation eventually eclipsed Corneille’s and he achieved a position in French literary history similar to that of Shakespeare in England.

David’s reputation as France’s most important living painter was assured when he exhibited his Oath of the Horatii (see figure 5) at the Paris Salon of 1785. In that work, viewers saw an image of the Roman past that spoke directly to their contemporary situation, calling for liberty and a new moral order. David conveyed this message through a reduction of form that echoes the narrative on which he based the painting’s iconography. According to the legend that had inspired Corneille’s play Horace, Rome decided to avoid an all-out war with its ancient rival Alba Longa by substituting single combat between two sets of triplets representing each side – the Horatii for Rome and the Curiatii for Alba Longa. In David’s Oath of the Horatii, broad gestures, determined stances, and visible muscular tension produce the stoic demeanor of the triplets, who swear allegiance to Rome as their father raises their swords. Their father, who is also committed to a Roman victory, is contrasted with his sons in a lessening of tension conveyed by his slightly bent elbows and knees. The stark simplicity of the background architecture and the sturdy Doric columns supporting plain round arches echo the stoicism of the male figures. The triple-arched wall both recalls the triumphal arches of ancient Rome and frames the groups of figures.

Figure 5 Jacques-Louis David, The Oath of the Horatii, 1784, 11 x 13 ft 11 3/8 in (3.30 x 4.25 m). Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

At the right, women and children reveal their anguish at the prospect of personal loss.1 The patriotic zeal of the Horatii triplets, willing to die for an ideal and composed of assertive diagonals, contrasts with the more realistic fatalism of the women, who are rendered in a more curvilinear manner than the men. Camilla, on the far right, is shown in a traditional pose of mourning. She is the sister of the Horatii, but is betrothed to one of the Curiatii. For her, therefore, the outcome of the combat cannot fail to end in tragedy.

In 1789, thirteen years after the American Revolution (1776), the French Revolution erupted in full force. Its impact, in Europe as well as in America, shattered the time-honored belief in the divine right of kings and led to the establishment of the First Republic, declared in 1792. Conflict between two factions of the republican revolutionary movement – the Girondists and the more radical Jacobins – followed, culminating in the Reign of Terror from September 1793 to July 1794. Led by the Jacobin lawyer and politician Maximilien Robespierre (1758–1794), the Terror resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of Girondists, aristocrats, and members of the clergy, who were considered enemies of the Revolution. David, himself a Jacobin and avid supporter of Robespierre, voted to guillotine the king, Louis XVI, and his queen, Marie Antoinette. Soon thereafter Robespierre was executed and the Jacobins lost their position of power, and with them David lost his. He went to jail twice for his revolutionary leanings, but he escaped execution and within a decade became an artist much admired by the emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte.

In the Salon of 1791 (see box, p.11), David exhibited his huge drawing study for a twenty-by-thirty-foot painting to be entitled The Tennis Court Oath (figure 6, p.12). Although never completed, the work remains an important historical and artistic document of revolutionary France. It was commissioned by the Jacobins to memorialize the event of June 20, 1789, when the deputies of the newly constituted National Assembly met at an indoor tennis court in Versailles and took an oath to secure the establishment of a new constitution. A pivotal revolutionary event, the oath marked the first official opposit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of illustrations

- Introduction

- 1: Neoclassicism

- 2: Romanticism

- 3: Realism

- 4: Impressionism

- 5: Post-Impressionism

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Plate section

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Further reading

- List of artists and works

- Index