- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

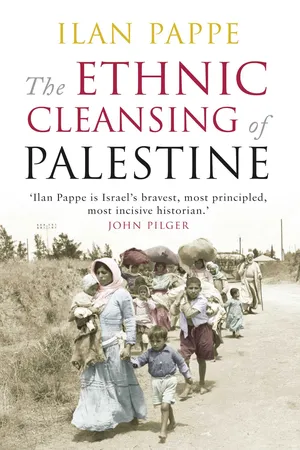

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine

About this book

The book that is providing a storm of controversy, from ‘Israel’s bravest historian’ (John Pilger)

Renowned Israeli historian, Ilan Pappe's groundbreaking work on the formation of the State of Israel.

'Along with the late Edward Said, Ilan Pappe is the most eloquent writer of Palestinian history.' NEW STATESMAN

Between 1947 and 1949, over 400 Palestinian villages were deliberately destroyed, civilians were massacred and around a million men, women, and children were expelled from their homes at gunpoint.

Denied for almost six decades, had it happened today it could only have been called 'ethnic cleansing'. Decisively debunking the myth that the Palestinian population left of their own accord in the course of this war, Ilan Pappe offers impressive archival evidence to demonstrate that, from its very inception, a central plank in Israel’s founding ideology was the forcible removal of the indigenous population. Indispensable for anyone interested in the current crisis in the Middle East.

***

'Ilan Pappe is Israel's bravest, most principled, most incisive historian.' JOHN PILGER

'Pappe has opened up an important new line of inquiry into the vast and fateful subject of the Palestinian refugees. His book is rewarding in other ways. It has at times an elegiac, even sentimental, character, recalling the lost, obliterated life of the Palestinian Arabs and imagining or regretting what Pappe believes could have been a better land of Palestine.' TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT

'A major intervention in an argument that will, and must, continue. There's no hope of lasting Middle East peace while the ghosts of 1948 still walk.' INDEPENDENT

Renowned Israeli historian, Ilan Pappe's groundbreaking work on the formation of the State of Israel.

'Along with the late Edward Said, Ilan Pappe is the most eloquent writer of Palestinian history.' NEW STATESMAN

Between 1947 and 1949, over 400 Palestinian villages were deliberately destroyed, civilians were massacred and around a million men, women, and children were expelled from their homes at gunpoint.

Denied for almost six decades, had it happened today it could only have been called 'ethnic cleansing'. Decisively debunking the myth that the Palestinian population left of their own accord in the course of this war, Ilan Pappe offers impressive archival evidence to demonstrate that, from its very inception, a central plank in Israel’s founding ideology was the forcible removal of the indigenous population. Indispensable for anyone interested in the current crisis in the Middle East.

***

'Ilan Pappe is Israel's bravest, most principled, most incisive historian.' JOHN PILGER

'Pappe has opened up an important new line of inquiry into the vast and fateful subject of the Palestinian refugees. His book is rewarding in other ways. It has at times an elegiac, even sentimental, character, recalling the lost, obliterated life of the Palestinian Arabs and imagining or regretting what Pappe believes could have been a better land of Palestine.' TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT

'A major intervention in an argument that will, and must, continue. There's no hope of lasting Middle East peace while the ghosts of 1948 still walk.' INDEPENDENT

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

An ‘Alleged’ Ethnic Cleansing?

It is the present writer’s view that ethnic cleansing is a well-defined policy of a particular group of persons to systematically eliminate another group from a given territory on the basis of religious, ethnic or national origin. Such a policy involves violence and is very often connected with military operations. It is to be achieved by all possible means, from discrimination to extermination, and entails violations of human rights and international humanitarian law . . . Most ethnic cleansing methods are grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and 1977 Additional Protocols.

Drazen Petrovic, ‘Ethnic Cleansing – An Attempt at Methodology’, European Journal of International Law, 5/3 (1994),

pp. 342–60.

pp. 342–60.

DEFINITIONS OF ETHNIC CLEANSING

Ethnic cleansing is today a well-defined concept. From an abstraction associated almost exclusively with the events in the former Yugoslavia, ‘ethnic cleansing’ has come to be defined as a crime against humanity, punishable by international law. The particular way some of the Serbian generals and politicians were using the term ‘ethnic cleansing’ reminded scholars they had heard it before. It was used in the Second World War by the Nazis and their allies, such as the Croat militias in Yugoslavia. The roots of collective dispossession are, of course, more ancient: foreign invaders have used the term (or its equivalents) and practised the concept regularly against indigenous populations, from Biblical times to the height of colonialism.

The Hutchinson encyclopedia defines ethnic cleansing as expulsion by force in order to homogenise the ethnically mixed population of a particular region or territory. The purpose of expulsion is to cause the evacuation of as many residences as possible, by all means at the expeller’s disposal, including non-violent ones, as happened with the Muslims in Croatia, expelled after the Dayton agreement of November 1995.

This definition is also accepted by the US State Department. Its experts add that part of the essence of ethnic cleansing is the eradication, by all means available, of a region’s history. The most common method is that of depopulation within ‘an atmosphere that legitimises acts of retribution and revenge’. The end result of such acts is the creation of a refugee problem. The State Department looked in particular at what happened around May 1999 in the town of Peck in Western Kosovo. Peck was depopulated within twenty-four hours, a result that could only have been achieved through advance planning followed by systematic execution. There had also been sporadic massacres, intended to speed up the operation. What happened in Peck in 1999 took place in almost the same manner in hundreds of Palestinian villages in 1948.1

When we turn to the United Nations, we find it employs similar definitions. The organisation discussed the concept seriously in 1993. The UN’s Council for Human Rights (UNCHR) links a state’s or a regime’s desire to impose ethnic rule on a mixed area – such as the making of Greater Serbia – with the use of acts of expulsion and other violent means. The report the UNCHR published defined acts of ethnic cleansing as including ‘separation of men from women, detention of men, explosion of houses’ and subsequently repopulating the remaining houses with another ethnic group. In certain places in Kosovo, the report noted, Muslim militias had put up resistance: where this resistance had been stubborn, the expulsion entailed massacres.2

Israel’s 1948 Plan D, mentioned in the preface, contains a repertoire of cleansing methods that one by one fit the means the UN describes in its definition of ethnic cleansing, and sets the background for the massacres that accompanied the massive expulsion.

Such references to ethnic cleansing are also the rule within the scholarly and academic worlds. Drazen Petrovic has published one of the most comprehensive studies on definitions of ethnic cleansing. He associates ethnic cleansing with nationalism, the making of new nation states, and national struggle. From this perspective he exposes the close connection between politicians and the army in the perpetration of the crime and comments on the place of massacres within it. That is, the political leadership delegates the implementation of the ethnic cleansing to the military level without necessarily furnishing any systematic plans or providing explicit instructions, but with no doubt as to the overall objective.3

Thus, at one point – and this again mirrors exactly what happened in Palestine – the political leadership ceases to take an active part as the machinery of expulsion comes into action and rolls on, like a huge bulldozer propelled by its own inertia, only to come to a halt when it has completed its task. The people it crushes underneath and kills are of no concern to the politicians who set it in motion. Petrovic and others draw our attention to the distinction between massacres that are part of genocide, where they are premeditated, and the ‘unplanned’ massacres that are a direct result of the hatred and vengeance whipped up against the background of a general directive from higher up to carry out an ethnic cleansing.

Thus, the encyclopedia definition outlined above appears to be consonant with the more scholarly attempt to conceptualise the crime of ethnic cleansing. In both views, ethnic cleansing is an effort to render an ethnically mixed country homogenous by expelling a particular group of people and turning them into refugees while demolishing the homes they were driven out from. There may well be a master plan, but most of the troops engaged in ethnic cleansing do not need direct orders: they know beforehand what is expected of them. Massacres accompany the operations, but where they occur they are not part of a genocidal plan: they are a key tactic to accelerate the flight of the population earmarked for expulsion. Later on, the expelled are then erased from the country’s official and popular history and excised from its collective memory. From planning stage to final execution, what occurred in Palestine in 1948 forms a clear-cut case, according to these informed and scholarly definitions, of ethnic cleansing.

Popular Definitions

The electronic encyclopedia Wikipedia is an accessible reservoir of knowledge and information. Anyone can enter it and add to or change existing definitions, so that it reflects – by no means empirically but rather intuitively – a wide public perception of a certain idea or concept. Like the scholarly and encyclopedic definitions mentioned above, Wikipedia characterises ethnic cleansing as massive expulsion and also as a crime. I quote:

At the most general level, ethnic cleansing can be understood as the forced expulsion of an ‘undesirable’ population from a given territory as a result of religious or ethnic discrimination, political, strategic or ideological considerations, or a combination of these.4

The entry lists several cases of ethnic cleansing in the twentieth century, beginning with the expulsion of the Bulgarians from Turkey in 1913 all the way up to the Israeli pullout of Jewish settlers from Gaza in 2005. The list may strike us as a bit bizarre in the way it incorporates within the same category Nazi ethnic cleansing and the removal by a sovereign state of its own people after it declared them illegal settlers. But this classification becomes possible because of the rationale the editors – in this case, everyone with access to the site – adopted for their policy, which is that they make sure the adjective ‘alleged’ precedes each of the historical cases on their list.

Wikipedia also includes the Palestinian Nakba of 1948. But one cannot tell whether the editors regard the Nakba as a case of ethnic cleansing that leaves no room for ambivalence, as in the examples of Nazi Germany or the former Yugoslavia, or whether they consider this a more doubtful case, perhaps similar to that of the Jewish settlers whom Israel removed from the Gaza Strip. One criterion this and other sources generally accept in order to gauge the seriousness of the allegation is whether anyone has been indicted before an international tribunal. In other words, where the perpetrators were brought to justice, i.e., were tried by an international judicial system, all ambiguity is removed and the crime of ethnic cleansing is no longer ‘alleged’. But upon reflection, this criterion must also be extended to cases that should have been brought before such tribunals but never were. This is admittedly more open-ended, and some clear-cut crimes against humanity require a long struggle before the world recognises them as historical facts. The Armenians learned this in the case of their genocide: in 1915, the Ottoman government embarked on a systematic decimation of the Armenian people. An estimated one million perished by 1918, but no individual or group of individuals has been brought to trial.

ETHNIC CLEANSING AS A CRIME

Ethnic cleansing is designated as a crime against humanity in international treaties, such as that which created the International Criminal Court (ICC), and whether ‘alleged’ or fully recognised, it is subject to adjudication under international law. A special International Criminal Tribunal was set up in The Hague in the case of the former Yugoslavia to prosecute the perpetrators and criminals and, similarly, in Arusha, Tanzania, in the case of Rwanda. In other instances, ethnic cleansing was defined as a war crime even when no legal process was instigated as such (for example, the actions committed by the Sudanese government in Darfur).

This book is written with the deep conviction that the ethnic cleansing of Palestine must become rooted in our memory and consciousness as a crime against humanity and that it should be excluded from the list of alleged crimes. The perpetrators here are not obscure – they are a very specific group of people: the heroes of the Jewish war of independence, whose names will be quite familiar to most readers. The list begins with the indisputable leader of the Zionist movement, David Ben-Gurion, in whose private home all early and later chapters in the ethnic cleansing story were discussed and finalised. He was aided by a small group of people I refer to in this book as the ‘Consultancy’, an ad-hoc cabal assembled solely for the purpose of plotting and designing the dispossession of the Palestinians.5 In one of the rare documents that records the meeting of the Consultancy, it is referred to as the Consultant Committee – Haveadah Hamyeazet. In another document the eleven names of the committee members appear, although they are all erased by the censor (nonetheless, as will transpire, I have managed to reconstruct all the names).6

This caucus prepared the plans for the ethnic cleansing and supervised its execution until the job of uprooting half of Palestine’s native population had been completed. It included first and foremost the top-ranking officers of the future Jewish State’s army, such as the legendary Yigael Yadin and Moshe Dayan. They were joined by figures unknown outside Israel but well grounded in the local ethos, such as Yigal Allon and Yitzhak Sadeh. These military men co-mingled with what nowadays we would call the ‘Orientalists’: experts on the Arab world at large and the Palestinians in particular, either because they themselves came from Arab countries or because they were scholars in the field of Middle Eastern studies. We will encounter some of their names later on as well.

Both the officers and the experts were assisted by regional commanders, such as Moshe Kalman, who cleansed the Safad area, and Moshe Carmel, who uprooted most of the Galilee. Yitzhak Rabin operated both in Lydd and Ramla as well as in the Greater Jerusalem area. Remember their names, but begin to think of them not just as Israeli war heroes. They did take part in founding a state for Jews, and many of their actions are understandably revered by their own people for helping to save them from outside attacks, seeing them through crises, and above all offering them a safe haven from religious persecution in different parts of the world. But history will judge how these achievements will ultimately weigh in the balance when the opposite scale holds the crimes they committed against the indigenous people of Palestine. Other regional commanders included Shimon Avidan, who cleansed the south and of whom his colleague, Rehavam Zeevi, who fought with him, said many years later, ‘Commanders like Shimon Avidan, the commander of the Givati Brigade, cleansed his front from tens of villages and towns’.7 He was assisted by Yitzhak Pundak, who told Ha’aretz in 2004, ‘There were two hundred villages [in the front] and these are gone. We had to destroy them, otherwise we would have had Arabs here [namely in the southern part of Palestine] as we have in Galilee. We would have had another million Palestinians’.8

And then there were the intelligence officers on the ground. Far from being mere collectors of data on the ‘enemy’, they not only played a major role in the cleansing but also took part in some of the worst atrocities that accompanied the systematic dispossession of the Palestinians. They were given the final authority to decide which villages would be destroyed and who among the villagers would be executed.9 In the memories of Palestinian survivors they were the ones who, after a village or neighbourhood had been occupied, decided the fate of its occupants, which could mean the difference between imprisonment and freedom, or life and death. Their operations in 1948 were supervised by Issar Harel, later the first person to head the Mossad and the Shabak, Israel’s secret services. His image is familiar to many Israelis. A short bulky figure, Harel had the modest rank of colonel in 1948, but was nonetheless the most senior officer overseeing all the operations of interrogation, blacklisting and the other oppressive features of Palestinian life under the Israeli occupation.

Finally, it bears repeating that from whatever angle you look at it – the legal, the scholarly, and up to the most populist – ethnic cleansing is indisputably identified today as a crime against humanity and as involving war crimes, with special international tribunals judging those indicted of having planned and executed acts of ethnic cleansing. However, I should now add that, in hindsight, we might think of applying – and, quite frankly, for peace to have a chance in Palestine we ought to apply – a rule of obsolescence in this case, but on one condition: that the one political solution normally regarded as essential for reconciliation by both the United States and the United Nations is enforced here too, namely the unconditional return of the refugees to their homes. The US supported such a UN decision for Palestine, that of 11 December 1948 (Resolution 194), for a short – all too short – while. By the spring of 1949 American policy had already been reoriented onto a conspicuously pro-Israeli track, turning Washington’s mediators into the opposite of honest brokers as they largely ignored the Palestinian point of view in general, and disregarded in particular the Palestinian refugees’ right of return.

RECONSTRUCTING AN ETHNIC CLEANSING

By adhering to the definition of ethnic cleansing as given above, we absolve ourselves from the need to go deeply into the origins of Zionism as the ideological cause of the ethnic cleansing. Not that the subject is not important, but it has been dealt with successfully by a number of Palestinian and Israeli scholars such as Walid Khalidi, Nur Masalha, Gershon Shafir and Baruch Kimmerling, among others.10 Although I would like to focus on the immediate background preceding the operations, it would be valuable for readers to recap the major arguments of these scholars.

A good book to begin with is Nur Masalha’s Expulsion of the Palestinians,11 which shows clearly how deeply rooted the concept of transfer was, and is, in Zionist political thought. From the founder of the Zionist movement, Theodor Herzl, to the main leaders of the Zionist enterprise in Palestine, cleansing the land was a valid option. As one of the movement’s most liberal thinkers, Leo Motzkin, put it in 1917:

Our thought is that the colonization of Palestine has to go in two directions: Jewish settlement in Eretz Israel and the resettlement of the Arabs of Eretz Israel in areas outside the country. The transfer of so many Arabs may seem at first unacceptable economically, but is nonetheless practical. It does not require too much money to resettle a Palestinian village on another land.12

The fact that the expellers were newcomers to the country, and part of a colonization project, relates the case of Palestine to the colonialist history of ethnic cleansing in North and South America, Africa and Australia, where white settlers routinely committed such crimes. This intriguing ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations, Maps and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1. An ‘Alleged’ Ethnic Cleansing?

- 2. The Drive for an Exclusively Jewish State

- 3. Partition and Destruction: UN Resolution 181 and its Impact

- 4. Finalising A Master Plan

- 5. The Blueprint for Ethnic Cleansing: Plan Dalet

- 6. The Phony War and the Real War over Palestine: May 1948

- 7. The Escalation of the Cleansing Operations: June–September 1948

- 8. Completing the Job: October 1948–January 1949

- 9. Occupation and its Ugly Faces

- 10. The Memoricide of the Nakba

- 11. Nakba Denial and the ‘Peace Process’

- 12. Fortress Israel

- Epilogue

- Illustration Section

- Endnotes

- Chronology

- Maps and Tables

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine by Ilan Pappe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.