- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

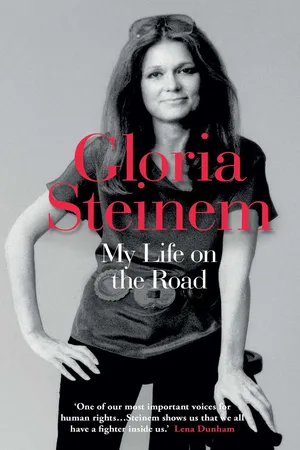

Gloria Steinem – writer, activist, organizer, and inspiring leader – tells a story she has never told before in this candid account of her life as a traveler, a listener and a catalyst for change

'A vital primer for any feminist activist.' Laura Bates

'A lightning rod to the head and heart... Women will read My Life on the Road, but men must.' James Patterson

Gloria Steinem had an itinerant childhood. Every fall, her father would pack the family into the car and they would drive across the country, in search of their next adventure. The seeds were planted: Steinem would spend much of her life on the road, as a journalist, organizer, activist, and speaker.

In vivid stories that span an entire career, Steinem writes about her time on the campaign trail, from Bobby Kennedy to Hillary Clinton; her early exposure to social activism in India; organizing ground-up movements in America; the taxi drivers who were "vectors of modern myths" and the airline stewardesses who embraced feminism; and the infinite contrasts, the "surrealism in everyday life" that Steinem encountered as she travelled back and forth across the country. With the unique perspective of one of the greatest feminist icons of the 20th and 21st centuries, here is an inspiring, profound, enlightening memoir of one woman's life-long journey.

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND THE HIT BBC SERIES, MRS. AMERICA

'An inspiring work, a call for action.' bell hooks

'One of the most important women of our time.' Diane von Furstenberg

'A vital primer for any feminist activist.' Laura Bates

'A lightning rod to the head and heart... Women will read My Life on the Road, but men must.' James Patterson

Gloria Steinem had an itinerant childhood. Every fall, her father would pack the family into the car and they would drive across the country, in search of their next adventure. The seeds were planted: Steinem would spend much of her life on the road, as a journalist, organizer, activist, and speaker.

In vivid stories that span an entire career, Steinem writes about her time on the campaign trail, from Bobby Kennedy to Hillary Clinton; her early exposure to social activism in India; organizing ground-up movements in America; the taxi drivers who were "vectors of modern myths" and the airline stewardesses who embraced feminism; and the infinite contrasts, the "surrealism in everyday life" that Steinem encountered as she travelled back and forth across the country. With the unique perspective of one of the greatest feminist icons of the 20th and 21st centuries, here is an inspiring, profound, enlightening memoir of one woman's life-long journey.

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND THE HIT BBC SERIES, MRS. AMERICA

'An inspiring work, a call for action.' bell hooks

'One of the most important women of our time.' Diane von Furstenberg

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access My Life on the Road by Gloria Steinem in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Biographies de sciences sociales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Sciences socialesSubtopic

Biographies de sciences socialesI.

My Father’s Footsteps

I COME BY MY ROAD HABITS HONESTLY.

There were only a few months each year when my father seemed content with a house-dwelling life. Every summer, we stayed in the small house he had built across the road from a lake in rural Michigan, where he ran a dance pavilion on a pier over the water. Though there was no ocean within hundreds of miles, he had named it Ocean Beach Pier, and given it the grandiose slogan “Dancing Over the Water and Under the Stars.”

On weeknights, people came from nearby farms and summer cottages to dance to a jukebox. My father dreamed up such attractions as a living chess game, inspired by his own love of chess, with costumed teenagers moving across the squares of the dance floor. On weekends, he booked the big dance bands of the 1930s and 1940s into this remote spot. People might come from as far away as Toledo or Detroit to dance to this live music on warm moonlit nights. Of course, paying the likes of Guy Lombardo or Duke Ellington or the Andrews Sisters meant that one rainy weekend could wipe out a whole summer’s profits, so there was always a sense of gambling. I think my father loved that, too.

But as soon as Labor Day had ended this precarious livelihood, my father moved his office into his car. In the first warm weeks of autumn, we drove to nearby country auctions, where he searched for antiques amid the household goods and farm tools. After my mother, with her better eye for antiques and her reference books, appraised them for sale, we got into the car again to sell them to roadside antique dealers anywhere within a day’s journey. I say “we” because from the age of four or so, I came into my own as the wrapper and unwrapper of china and other small items that we cushioned in newspaper and carried in cardboard boxes over country roads. Each of us had a role in the family economic unit, including my sister, nine years older than I, who in the summer sold popcorn from a professional stand my father bought her.

But once the first frost turned the lake to crystal and the air above it to steam, my father began collecting road maps from gas stations, testing the trailer hitch on our car, and talking about such faraway pleasures as thin sugary pralines from Georgia, all-you-can-drink orange juice from roadside stands in Florida, or slabs of salmon fresh from a California smokehouse.

Then one day, as if struck by a sudden whim rather than a lifelong wanderlust, he announced that it was time to put the family dog and other essentials into the house trailer that was always parked in our yard, and begin our long trek to Florida or California.

Sometimes this leave-taking happened so quickly that we packed more frying pans than plates, or left a kitchen full of dirty dishes and half-eaten food to greet us like Pompeii on our return. My father’s decision always seemed to come as a surprise, even though his fear of the siren song of home was so great that he refused to put heating or hot water into our small house. If the air of early autumn grew too chilly for us to bathe in the lake, we heated water on a potbellied stove and took turns bathing in a big washtub next to the fireplace. Since this required the chopping of wood, an insult to my father’s sybaritic soul, he had invented a wood-burning system all his own: he stuck one end of a long log into the fire and let the other protrude into the living room, then kicked it into the fireplace until the whole thing turned to ash. Even a pile of cut firewood in the yard must have seemed to him a dangerous invitation to stay in one place.

After he turned his face to the wind, my father did not like to hesitate. Only once do I remember him turning back, and even then my mother had to argue strenuously that the iron might be burning its way through the ironing board. He would buy us a new radio, new shoes, almost anything rather than retrace the road already traveled.

At the time, I didn’t question this spontaneity. It was part of the family ritual. Now I wonder if seasonal signals might be programmed into the human brain. After all, we’ve been a migratory species for nearly all our time on earth, and the idea of a settled life is very new. If birds will abandon their young rather than miss the moment to begin a flight of thousands of miles, what migratory signals might our own cells still hold? Perhaps my father—and even my mother, though she paid a far higher price for our wanderings—had chosen a life in which those signals could still be heard.

My parents also lived off the land—in their own way. We never started out with enough money to reach our destination, not even close. Instead, we took a few boxes of china, silver, and other small antiques from those country auctions, and used them to prime the process of buying, selling, and bartering our way along the southern route to California, or still farther south to Florida and the Gulf of Mexico. It was a pattern that had begun years before I was born, and my father knew every roadside dealer in antiques along the way, as a desert traveler knows each oasis. Still, some shops were always new or under new management, and it must have taken courage to drive up in our dusty car and trailer, knowing that we looked less like antique dealers than like migrants forced to sell the family heritage. If a shop owner treated us with too much disdain, my father was not above letting him think we really were selling our possessions. Then he would regain his dignity by elaborating on his triumph once he was back in the car.

Since my parents believed that travel was an education in itself, I didn’t go to school. My teenage sister enrolled in whatever high school was near our destination, but I was young enough to get away with only my love of comic books, horse stories, and Louisa May Alcott. Reading in the car was so much my personal journey that when my mother urged me to put down my book and look out the window, I would protest, “But I just looked an hour ago!” Indeed, it was road signs that taught me to read in the first place—perfect primers, when you think about it. coffee came with a steaming cup, hot dogs and hamburgers had illustrations, a bed symbolized hotel, and graphics warned of bridge or road work. There was also the magic of rhyming. A shaving cream company had placed small signs at intervals along the highway, and it was anticipating the rhyme that kept me reading:

If you

don’t know

whose signs

these are

you can’t have

driven

very far.

Burma Shave

Later, when I read that Isak Dinesen recited English poems to her Kikuyu workers in Kenya—and they requested them over and over again, even though they didn’t understand the words—I knew exactly what they meant. Rhyming in itself is magic.

In this way, we progressed through rain and sandstorms, heat waves and cold winds, one small part of a migration of American nomads. We ate in diners where I developed a lifetime ambition to run one with blue gingham curtains and bran muffins. In the car during the day, we listened to radio serials, and at night, to my father singing popular songs to stay awake.

I remember driving into the pungent smell of gas stations, where men in overalls emerged from under cars, wiping their hands on greasy rags and ushering us into a mysterious and masculine world. Inside were restrooms that were not for the queasy or faint of heart. Outside were ice chests from whose watery depths my father would pluck a Coke, drink it down in one amazing gulp, and then search for a bottle of my beloved Nehi Grape Soda so I could sip it slowly until my tongue turned purple. The attendants themselves were men of few words, yet they gave freely of their knowledge of the road and the weather, charging only for the gas they sold.

I think of them now as tribesmen along a trading route, or suppliers of caravans where the Niger enters the Sahara, or sailmakers serving the spice ships of Trivandrum. And I wonder: Were they content with their role, or was this as close to a traveling life as they could come?

I remember my father driving on desert roads made of wired-together planks, with only an occasional rattlesnake ranch or one-pump gas station to break the monotony. We stopped at ghost towns that had been emptied of every living soul, and saw sand dunes pushing against lurching buildings, sometimes shifting to reveal a brass post office box or other treasure. I placed my hands on weathered boards, trying to imagine the people they once had sheltered, while my parents followed the more reliable route of asking the locals. One town had died slowly after the first asphalt road was laid too far away. Another was emptied by fear when a series of mysterious murders were traced to the sheriff. A third was being repopulated as a stage set for a western movie starring Gary Cooper, with sagging buildings soaked in kerosene to make an impressive fire, and signs placed everywhere to warn bystanders away.

Ever challenged by rules, my father took us down the road to a slack place in the fence, and sneaked us onto the set. Perhaps assuming that we had permission from higher-ups, the crew treated us with deference. I still have a photo my father took of me standing a few feet from Gary Cooper, who is looking down at me with amusement, my head at about the height of his knee, my worried gaze fixed on the ground.

As a child who wanted too much to fit in, I worried that we would be abandoned like those towns one day, or that my father’s rule-breaking would bring down some nameless punishment. But now I wonder: Without those ghost towns that live in my imagination longer than any inhabited place, would I have known that mystery leaves a space for us when certainty does not? And would I have dared to challenge rules later in life if my father had obeyed them?

Whenever we were flush, we traded the cold concrete showers of trailer parks for taking turns at a hot bath in a motel. Afterward, we often went to some local movie palace, a grand and balconied place that was nothing like the warrens of viewing rooms today. My father was always sure that a movie and a malted could cure anything—and he wasn’t wrong. We would cross the sidewalk that sparkled with mica, enter the gilded lobby with fountains where moviegoers threw pennies for luck and future return, and leave our cares behind. In that huge dark space filled with strangers, all facing huge and glowing images, we gave ourselves up to another world.

Now I know that both the palaces and the movies were fantasies created by Hollywood in the Depression, the only adventures most people could afford. I think of them again whenever I see subway riders lost in paperback mysteries, the kind that Stephen King’s waitress mother once called her “cheap sweet vacations”—and so he writes them for her still. I think of them when I see children cramming all five senses into virtual images online, or when I pass a house topped by a satellite dish almost as big as it is, as if the most important thing were the ability to escape. The travel writer Bruce Chatwin wrote that our nomadic past lives on in our “need for distraction, our mania for the new.”1 In many languages, even the word for human being is “one who goes on migrations.” Progress itself is a word rooted in a seasonal journey. Perhaps our need to escape into media is a misplaced desire for the journey.

Most of all from my childhood travels, I remember the first breath of salt air as we neared our destination. On a California highway overlooking the Pacific or a Florida causeway that cut through the Gulf of Mexico like Moses parting the Red Sea, we would get out of our cramped car, stretch, and fill our lungs in an ontogeny of birth. Melville once said that every path leads to the sea, the source of all life. That conveys the fatefulness of it—but not the joy.

Years later, I saw a movie about a prostituted woman in Paris who saves money to take her young daughter on a vacation by the sea. As their train full of workers rounds a cliff, the shining limitless waters spread out beneath them—and suddenly all the passengers begin to laugh, throw open the windows, and toss out cigarettes, coins, lipstick: everything they thought they needed a moment before.

This was the joy I felt as a wandering child. Whenever the road presents me with its greatest gift—a moment of unity with everything around me—I still do.

ANOTHER TRUTH OF MY EARLY WANDERINGS is harder to admit: I longed for a home. It wasn’t a specific place but a mythical neat house with conventional parents, a school I could walk to, and friends who lived nearby. My dream bore a suspicious resemblance to the life I saw in movies, but my longing for it was like a constant low-level fever. I never stopped to think that children in neat houses and conventional schools might envy me.

When I was ten or so, my parents separated. My sister was devastated, but I had never understood why two such different people were married in the first place. My mother often worried her way into depression, and my father’s habit of mortgaging the house, or otherwise going into debt without telling her, didn’t help. Also, wartime gas rationing had forced Ocean Beach Pier to close, and my father was on the road nearly full time, buying and selling jewelry and small antiques to make a living. He felt he could no longer look after my sometimes-incapacitated mother. Also, she wanted to live near my sister, who was finishing college in Massachusetts, and now I was old enough to be her companion.

We rented a house in a small town, and spent most of one school year there. It was the most conventional life we would ever lead. After my sister graduated and left for her first grown-up job, my mother and I moved to East Toledo and an ancient farmhouse where her family had once lived. As with all inferior things, this part of the city was given an adjective while the rest stole the noun. What once had been countryside was crowded with the small houses of factory workers. They surrounded our condemned and barely habitable house on three sides, with a major highway undercutting its front porch and trucks that rattled our windows. Inside this remnant of her childhood, my mother disappeared more and more into her unseen and unhappy world.

I was always worried that she might wander into the streets, or forget that I was in school and call the police to find me—all of which sometimes happened. Still, I thought I was concealing all this from my new friends. Most were quiet about their families for some reason, from speaking only Polish or Hungarian at home, to a father who drank too much or an out-of-work relative sleeping on the couch. By tacit agreement, we tended to meet on street corners. Only many years later would I meet a high school classmate who confessed that she had always worried about me, that my mother was called the Crazy Lady of the neighborhood.

During those years, my mother told me more about her early life. Long before I was born, she had been a rare and pioneering woman reporter, work that she loved and had done so well that she was promoted from social reporting to Sunday editor for a major Toledo newspaper. She had stayed on this path for a decade after marrying my father, and six years after giving birth to my sister. She was also supporting her husband’s impractical dreams and debts, suffering a miscarriage and then a stillbirth, and falling in love with a man at work: perhaps the man she should have married. All this ended in so much self-blame and guilt that she suffered what was then called a nervous breakdown, spent two years in a sanatorium, and emerged with an even greater feeling of guilt for having left my sister in her father’s care. She also had become addicted to a dark liquid sedative called chloral hydrate. Without it, she could be sleepless for days and hallucinate. With it, her speech was slurred and her attention slowed. Once out of the sanatorium, my mother gave up her job, her friends, and everything she loved to follow my father to isolated rural Michigan, where he was pursuing his dream of building a summer resort. In this way, she became the mother I knew: kind and loving, with flashes of humor and talent in everything from math to poetry, yet also without confidence or stability.

While I was living...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE

- CONTENTS

- PRELUDE

- INTRODUCTION: Road Signs

- CHAPTER I My Father’s Footsteps

- CHAPTER II Talking Circles

- CHAPTER III Why I Don’t Drive

- CHAPTER IV One Big Campus

- CHAPTER V When the Political Is Personal

- CHAPTER VI Surrealism in Everyday Life

- CHAPTER VII Secrets

- CHAPTER VIII What Once Was Can Be Again

- AFTERWORD: Coming Home

- NOTES OF GRATITUDE

- NOTES

- INDEX

- COPYRIGHT