- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

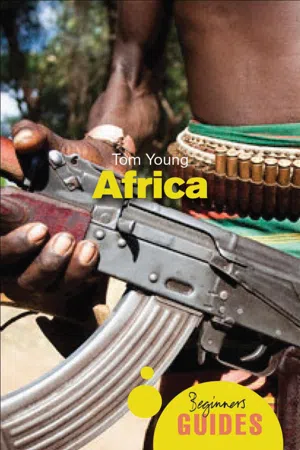

Vast, diverse, dynamic, and turbulent, the true nature of Africa is often obscured by its poverty-stricken image. In this controversial and gripping guide, Tom Young cuts through the emotional hype to critically analyse the continent's political history and the factors behind its dismal economic performance. Maintaining that colonial influences are often overplayed, Young argues that much blame must lie with African governments themselves and that Western aid can often cause as much harm as good.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Introduction: making sense of Africa

- 1 Africa before colonialism

- 2 Colonial rule and nationalist revolt

- 3 Independent Africa: success and failure

- 4 Conflict, war, and intervention

- 5 Can outsiders change Africa?

- By way of conclusion

- Notes

- Further reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Africa by Tom Young in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.