![]()

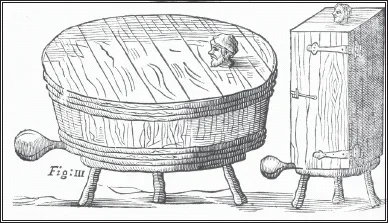

Sweating tubs used in the seventeenth-century treatment of syphilis. (The Royal Society)

1. THE HARDEST KNIFE ILL-USED:

Shakespeare’s Tremor

The real mystery of Shakespeare, a thousand times more mysterious than any matter of the will, is: why is it that—unlike Dante, Cervantes, Chaucer, Tolstoy, whomever you wish—he makes what seems a voluntary choice to stop writing?

—Harold Bloom

In Shakespeare’s tomb lies infinitely more than Shakespeare ever wrote.

—Herman Melville, “Hawthorne and His Mosses”

Twenty years he lived in London . . . Twenty years he dallied there between conjugal love and its chaste delights and scortatory love and its foul pleasures.

—James Joyce, Ulysses

His fitful fever returned. Master Shakespeare pulled the hood of his cloak down low over his eyes and hurried from his lodgings in Bishopsgate, walking as quickly as he could on his hobbled legs. He awkwardly dodged a pair of rambling pigs and picked his way through the dung and muck of the city streets. The stench and filth rarely troubled him now, as they had when he first came here from the country. Nearer the bridge, the clamour of the city increased: the clatter of carts, the cries of street peddlers, the gossip of alewives, the drunken braggadocio of London gallants. A black-clad Puritan surveyed the scene sourly and made brief eye contact with Will. The player hung his head and balled his hands into fists—to hide the telltale rash on his palms.

London Bridge was marvellous and strange, a massive structure built over with splendid houses. With relief he entered the dark, claustrophobic tunnel beneath the dwellings. Inside, a continual roar of noise: the tidal rush of water between the ancient piers; waterwheels creaking; apprentices brawling; carters disputing the right-of-way; a blind fiddler playing; sheep bleating on their way to Eastcheap, bound for slaughter. He left the shelter of the bridge, and emerged into painful sunlight on the other side. His shins throbbed and his muscles ached. In spite of himself, he peered up at the great stone gate at the end of the bridge, adorned with traitors’ heads on pikes. Shreds of mouldy flesh clung to the grinning skulls, their tattered hair bleached by sun and rain.

In Southwark, he heard the barking mastiffs and the howling crowd at the Bear Garden. He imagined old Sackerson the bear bellowing, lashing out with his claws, chained to a post, set on by dogs. A glimpse of ragged children playing in an alley filled him with thoughts of home and a pang of loneliness and shame. Before a row of brothels he saw a scabby beggar-woman with sunken nose and ulcerated shins. After years of faithful service in the stews, she has been turned out in the street to die of the pox. A chill of fear ran up his spine, and he looked away.

There was a pounding in his head and he felt dull and stupid. He circled many times through a maze of flyblown houses before he stumbled on the place. A servant showed him down a set of stairs. The bard descended into a hot cellar reeking of sulphur. A vast oven filled the room with flickering orange light. The sweaty heads of groaning men peered out from large wooden tubs. But the tubs were not filled with water. A sallow and emaciated man carrying iron tongs scurried round, feeding hot bricks into the tubs through a trapdoor. He poured vinegar onto the heaps of bricks and acrid steam rose up, making the glistening men within moan and shake.

The doctor suddenly appeared beside Will, startling him. He was sleek and prosperous, with a dainty goatee. Though he smiled reassuringly, the poet noticed that he kept a safe distance. In a soothing, urbane voice, the physician explained the treatment: stewed prunes to evacuate the bowels; succulent meats to ease digestion; cinnabar and the sweating tub to cleanse the disease from the skin. The doctor warned of minor side effects: uncontrolled drooling, fetid breath, bloody gums, shakes and palsies. Yet desperate diseases called for desperate remedies, of course.

Shakespeare extended a handful of silver coins. The physician took them with a gloved hand, scrutinized them carefully, and put them in his purse with the hint of a smirk. He pointed Will toward the skinny, pallid man tending bricks at the great oven. When the poet looked round again, the doctor had vanished.

The gaunt man tending the bricks was not quite right in the head. His hands shook, and he seemed both timorous and irritable. When he saw the poet’s rash, he cackled and slobbered, revealing a mouth full of rotten teeth. “Bit by a Winchester goose, eh? Ha-ha! A few good sweats will fix that, my lad. Into the powdering tub with you, then!”

The poet stripped and stood ashamed, his flesh covered in scaly blots. He nervously clambered over the side of a tub, and sat down on a plank nailed to the side. Under the plank, the wooden bottom had been removed, leaving an earthen pit. The queer thin man clumsily secured a heavy lid over the top of the tub, leaving an opening just large enough for the poet’s head. Then he popped open the trapdoor at the base of the tub and placed a hot metal plate at the poet’s feet. He tossed red powder on the plate. The dust disappeared in a mephitic bloom of hissing fumes. The doctor’s man repeated this again and again, until Will began to gag. A fine metallic powder settled on his body. The thin man piled hot bricks into the pit under the seat, and doused them with vinegar. As the acid waves of steam billowed upward, the bard started to tremble and sweat. This week would not be a pleasant one.

Even those who know little about Shakespeare are aware that there is a sort of controversy about the authorship of his plays. A vocal and eccentric minority doubts that a man of Shakespeare’s background could possess literary genius, and speculates his plays were really written by an aristocrat who wished for some reason to remain anonymous. This belief rests on two snobbish and mistaken assumptions: first, that a great deal of formal education is essential for great writing; and second, that creativity depends on wealth and comfort. A good case could be made that the exact opposite is true. Many great authors were largely self-taught, and either did not attend university or dropped out. Furthermore, a dose of youthful misery may help a writer by serving as a powerful stimulus to fantasy and imagination. A recurrent biographical pattern in great writers is a happy early childhood, followed by an adolescence made insecure by financial catastrophe, the loss of a parent, or other traumas. Such was the case with William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare was born in April 1564, in the market town of Stratford. We know almost nothing about his mother Mary, but quite a lot about his father. John Shakespeare combined something of Falstaff’s wit and rascality, Kent’s stubbornness and loyalty, and Lear’s feckless ill judgment. He made a lawful fortune from the glove trade, and an illegal one from usury and black market wool dealing. His fellow citizens liked him well enough to elect him the town’s bailiff, an office akin to that of mayor today. However, the gossamer prosperity of the Shakespeares unravelled in William’s teenage years, as John ran afoul of the law and lost much of his money and his lands. Elizabethan England was something between a modern constitutional monarchy and a police state. Spies and informers enforced religious orthodoxy and an oppressive system of trade regulations and monopolies. John Shakespeare was fined heavily, not only for his shady business practices, but also for his repeated failures to attend Protestant services, one of several signs that the family were probably closet Catholics.

If John Shakespeare once hoped to send his brilliant oldest son to get a gentleman’s university education, near bankruptcy now made this impossible. Young Will would have studied Latin and rhetoric in the local grammar school until the age of fifteen or sixteen, probably getting more formal education than Dickens, Yeats, or Herman Melville would receive. He then may have served as a tutor in a noble Catholic household in Lancashire. By age eighteen, he was back in Stratford and hastily wed to Anne Hathaway, twenty-six years old and two months pregnant at the time of the marriage. According to tradition, Will toiled in his father’s glove shop, and might also have moonlighted as a scrivener or a law clerk. Anne gave birth to the couple’s daughter Susanna in May 1583, followed by the twins, Hamnet and Judith, in February 1585. Shortly thereafter, Shakespeare went to seek his fortune in London. According to a durable—if somewhat dubious—Stratford legend, Shakespeare was whipped for poaching deer on the lands of one Sir Thomas Lucy, a notorious persecutor of local Catholics. Will made matters worse by posting a lampoon of Lucy on his park gate, and fled town one step ahead of Lucy’s thugs.

London was home to a burgeoning and intensely competitive theatre scene. Some playwrights were university graduates; others, such as Shakespeare, Kyd, and Jonson, were not. Shakespeare’s quick success, rural origins, and lack of a university degree made him the natural target of jealous attacks from the University Wits. These included Robert Greene, George Peele, and that great spendthrift of language, Thomas Nashe, a trio as noted for their depravity as for their abundant literary talents. All three would soon be dead. Their enemies blamed their passing on the pox, or syphilis, the dread disease that became a Shakespearian obsession.

By the early 1590s, Shakespeare had obtained the patronage of Henry Wriothesley, the Earl of Southampton. Wriothesley was an effete dandy of flexible sexuality, with a penchant for poetry. Both of Shakespeare’s racy, best-selling narrative poems, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece, are dedicated to him. The dedication for Lucrece, published in 1594, suggests that by then Shakespeare and Southampton were on familiar terms: “The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end . . . what I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours.” According to Shakespeare’s earliest biographer, Nicholas Rowe, Southampton once presented Shakespeare with £1000, a staggering (and almost certainly exaggerated) sum of money. Thus, by the time Shakespeare was middle-aged, he had achieved substantial wealth and fame. However, his success was blighted by the death of his only son Hamnet in 1596, and perhaps also by a serious health scare that may have left deep marks on his writing.

D. H. Lawrence was struck by how saturated some of Shakespeare’s work is with venereal disease: “I am convinced that some of Shakespeare’s horror and despair, in his tragedies, arose from the shock of his consciousness of syphilis.” Anthony Burgess was probably the first commentator with the effrontery to suggest that Shakespeare himself had syphilis. In his novel Nothing Like the Sun, Burgess depicted the poor bard as a pocky cuckold. He later characterized Shakespeare as having a “gratuitous venereal obsession,” an observation subsequently echoed by scholars Katherine Duncan-Jones and Harold Bloom.

References to syphilis in Shakespeare are more abundant, intrusive and clinically exact than those of his contemporaries. For example, there are only six lines referring to venereal disease in all seven plays of Christopher Marlowe. However, forty-three lines in Measure for Measure, fifty-one lines in Troilus and Cressida, and sixty-five lines in Timon of Athens unequivocally allude to syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

References to syphilis and STDs are not uniformly distributed throughout Shakespeare’s plays. In his first fourteen plays, up to The Merchant of Venice in 1596, there is an average of only three lines per play on venereal disease. (Most of these occur in The Comedy of Errors, dated from 1592–3, which contains twenty-three lines referring to STDs.) In the next twenty plays, from 1597’s Henry IV Part 1 to Cymbeline in 1609, there is an average of fifteen lines per play. The final four plays, The Winter’s Tale, The Tempest, Henry VIII, and Two Noble Kinsmen, average less than two lines per play referring to syphilis and other STDs. (These last two plays are generally accepted as being roughly equal collaborations between Shakespeare and John Fletcher.)

Could Shakespeare’s mid-career explosion of syphilitic content be explained by a general increase in bawdry on the Jacobean and late Elizabethan stages? Perhaps, but this would not explain why Shakespeare takes up the subject of syphilis in the early play The Comedy of Errors, only to drop it and return to it with a vengeance later on. Of course, Shakespeare’s interest in syphilis does not mean that he was personally infected. Shakespeare would be well aware of the effects of syphilis on London’s literary bohemia of the 1590s, just as an observer of the New York arts scene of the 1980s would be unpleasantly familiar with the ravages of AIDS. But is there evidence that Shakespeare’s own lifestyle put him at risk for syphilis?

Shakespeare’s marriage to Anne Hathaway was marked by long periods of separation. For most of their life, Will lived and worked in London, while Anne was home in Stratford. They had no children after 1585, when Anne was only twenty-nine. Perhaps this was related to obstetrical complications from the birth of the twins, but it might also suggest that their sexual congress was infrequent. Infamously, he bequeathed her only the “second-best bed.” (Despite the ingeniously benign explanations of Shakespeare’s biographers, it is hard to believe that the supreme master of the English language intended this as anything other than a sly, final insult.) Away from home, did Shakespeare expend much energy seeking better beds? In a 1602 diary entry, a law student, John Manningham, recorded this salacious anecdote about the playwright and the actor Richard Burbage:

Upon a time when Burbage played Richard the Third, there was a citizen grew so far in liking with him that before she went from the play she appointed him to come that night unto her by the name of Richard the Third. Shakespeare, overhearing their conversation, went before, was entertained, and at his game ere Burbage came. Then message being brought that Richard the Third was at the door, Shakespeare caused return to be made that William the Conqueror was before Richard the Third.

Even if this story seems too clever to be true, it suggests Shakespeare enjoyed a popular reputation as something less than a paragon of marital fidelity. Shakespeare’s high sexual alertness is also borne out by his robust ribald vocabulary. In Shakespeare’s Bawdy, Eric Partridge defines 1418 sexual or vulgar expressions in the works of Shakespeare, in a glossary of over 200 pages. Shakespeare’s amorous reputation is further reinforced in the Sonnets, and especially in a peculiar poem entitled Willobie His Avisa, published in 1594.

Willobie His Avisa purports to be an earnest moral tract about a virtuous wife who spurns the advances of her would-be seducers. The book was popular and went through several printings, probably because it was actually a literary hoax and satire of the sexual mores of prominent Elizabethans. Authorities found it subversive, and enhanced its scandalous cachet by confiscating and burning copies of it in 1599.

The origins of Willobie His Avisa are obscure. In the book’s introduction, one Hadrian Dorrell claims to have found the manuscript of Avisa in the bedchamber of his friend and fellow Oxford student Henry Willobie. Willobie is away on military service, and Dorrell is so impressed with the epic poem that he cannot resist preparing it for publication. Needless to say, there is no record of a Hadrian Dorrell having attended Oxford at this time, although there was a real Henry Willobie (or Willoughby) at Oxford, who conveniently died in 1596. It remains unclear whether Willobie was the real author of Avisa, whether he was the butt of a sophomoric prank, or whether he was only a handy stalking horse for the actual author.

Various failed suitors of Avisa are mocked in the first half of the poem. For example, “Caveleiro,” who may represent an Elizabethan noble with the equestrian moniker of Sir Ralph Horsey, is ridiculed as syphilitic: his “wanny cheeks” and “shaggy locks” make Avisa “fear the piles, or else the pox.” The second half of the poem concerns the vain attempts of “H. W.” to woo Avisa. H.W. is given cynical romantic advice by a man expert in the arts of seduction, the “old player” “W.S.,” his “familiar friend.” In this passage, the passion of H.W. for the chaste Avisa is described in vocabulary evocative of venereal disease:

H.W. being suddenly infected with the contagion of a fantastical fit . . . at length not able any longer to endure the burning heat of so fervent a humour, betrayed the secrecy of his disease unto his familiar friend W.S. who not long before had tried the courtesy of like passion, and was now recovered of the like infection . . . he now would secretly laugh at his friend’s folly, that had given occasion not long before unto others to laugh at his own . . . he determined to see whether it would sort to a happier end for this new actor, than it did for the old player. But at length this Comedy was liken to have grown to a Tragedy, by the weak and feeble estate H.W. was brought into . . . until Time and Necessity, being his best physicians brought him a plaster, if not to heal, yet in part to ease his malady. In all which discourse is lively represented the unruly rage of unbridled fancy, having the reins to rove at liberty, with the diverse and sundry changes of affections and temptations, which Will, set loose from Reason, can devise . . .

The pointed references to a “new actor,” an “old player,” “Comedy,” “Tragedy,” “Will,” and a doggerel parody of Shakespeare that follows, strongly suggest that the “old player” is William Shakespeare. Could H.W., the “new actor,” be Shakespeare’s pansexual patron, Henry Wriothesley? If Wriothesley, one of the kingdom’s most prominent nobles, had been the major target of the book’s satire, this would explain why the Elizabethan authorities were compelled to ...