- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

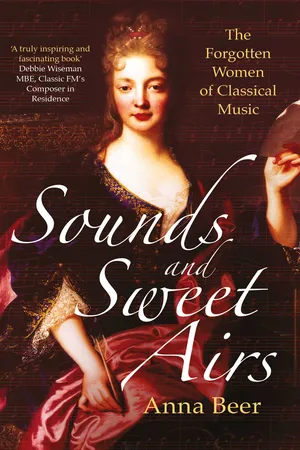

The hidden history of the women who dared to write music in a man’s world.

‘Lucid, engaging and exuberant... [Sounds and Sweet Airs] is terrifically enjoyable and accessible, and leaves one hankering for a second volume.’ The Sunday Times

Francesca Caccini. Barbara Strozzi. Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre. Marianna Martines. Fanny Hensel. Clara Schumann. Lili Boulanger. Elizabeth Maconchy.

Since the birth of classical music, women who dared compose have faced a bitter struggle to be heard. In spite of this, female composers continued to create, inspire and challenge. Yet even today so much of their work languishes unheard.

Anna Beer reveals the highs and lows experienced by eight composers across the centuries, from Renaissance Florence to twentieth-century London, restoring to their rightful place exceptional women whom history has forgotten.

‘Lucid, engaging and exuberant... [Sounds and Sweet Airs] is terrifically enjoyable and accessible, and leaves one hankering for a second volume.’ The Sunday Times

Francesca Caccini. Barbara Strozzi. Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre. Marianna Martines. Fanny Hensel. Clara Schumann. Lili Boulanger. Elizabeth Maconchy.

Since the birth of classical music, women who dared compose have faced a bitter struggle to be heard. In spite of this, female composers continued to create, inspire and challenge. Yet even today so much of their work languishes unheard.

Anna Beer reveals the highs and lows experienced by eight composers across the centuries, from Renaissance Florence to twentieth-century London, restoring to their rightful place exceptional women whom history has forgotten.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sounds and Sweet Airs by Anna Beer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Music BiographiesChapter One

Caccini

It is carnival time in Florence, and the Medici court is celebrating a great military victory against the Ottoman Turk achieved by their honoured guest, Crown-Prince Wladislaw Sigismund Vasa of Poland. No matter that the Battle of Khotyn, four years earlier, had been in reality a shambolic, bloody stalemate in which Wladislaw had played little active part. A lavish, spectacular entertainment is needed, one that not only demonstrates the triumph of goodness over evil, but the immense wealth and power of the Medici family, rulers of the grand duchy of Tuscany. The story chosen will tell of a wicked sorceress, Alcina, who seduces a knight, Ruggiero, entraping him on her island in order to take her pleasure. Worse still, he, and a host of other previous victims, seem to enjoy the experience. Fortunately, however, a ‘good’ witch, Melissa, triumphs over Alcina, and liberates Ruggiero and his fellows. Part opera, part ballet, no expense is spared in the production, which will end with an extraordinary balletto a cavallo (dancing horses) that the audience watches from the balconies and terraces of the Villa Poggio Imperiale, a ruinously expensive symbol of Medici power, linked to the city of Florence below by a tree-lined avenue.

The date is 3 February 1625, and the entertainment is La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina (The Liberation of Roger from the Island of Alcina). The composer is thirty-six-year-old Francesca Caccini, working at the height of her career. Many forces and factors have contributed towards this remarkable moment: Caccini was, for example, lucky to be the daughter of two exceptional musicians; she was fortunate to have been born in Florence, the creative centre of the Medici world. But these propitious circumstances of breeding and location are as nothing when set against the simple fact that Francesca Caccini is a woman. Every note on every score that Caccini writes offers a challenge to the dominant values of the world beyond Villa Poggio Imperiale. La liberazione is a hard-won triumph.

As a young girl, Francesca had been set on her path to this remarkable February day in the hills above Florence by Giulio, her ambitious, talented father. Her mother, Lucia di Filippo Gagnolandi, died when Francesca was only five, leaving her daughter with little except the inheritance of a beautiful singing voice, and leaving her husband with three children under the age of six, and a son, Pompeo, aged fourteen, from an earlier liaison. Giulio’s second marriage to an impoverished eighteen-year-old singer, Margherita di Agostino della Scala, known as ‘Bargialli’, did nothing to shore up his finances, but did introduce another talented singer to the Caccini stable. Growing up as the daughter of Giulio Caccini would prove to be a mixed blessing. On the one hand, he was the second most highly paid composer and musician on the staff of the Medici household, and renowned as the author of by far the most influential singing manual of the seventeenth century, Le nuove musiche, published in 1601, and then translated and imitated throughout Europe.* On the other hand, Giulio was proud to the point of self-destructiveness (house arrest followed his refusal to acknowledge a social superior in the street); profligate financially and sexually (a love of gambling made it hard to support his, at a guess, ten children by three women); and sought to dominate his immediate family, sometimes, it seems, simply for the sake of it, as when he withheld the dowry of Francesca’s younger sister, Settimia. Pompeo, Giulio’s eldest son, even apparently allowed himself to be charged with the rape of his intended wife, Ginevra, so that the courts would require him to marry the young woman, since it was the only way to circumvent his father’s opposition to the union. As for Settimia, Giulio eventually paid the dowry in 1611 when her new husband’s family abducted her and held her for ransom in the city of Lucca. This particular crisis precipitated the final break-up of the Caccini family as a performing group, but until that point, and for many years, Giulio’s women had been used to showcase his exceptional talents as a composer and a teacher. Living or dead, they served to display his ability, as he explained to his readers: ‘How excellently the tremolo and the trill were learned by my late wife [Lucia] . . . may be adjudged by those who heard her sing during her life, as also I leave to the judgment of those who can now hear in the present wife [Margherita] how exquisitely they are done by her.’

It was Francesca’s exceptional musical talent, however, that offered Giulio his greatest opportunity. For years, his ego and drive had ensured his success as a composer, performer and teacher in the competitive and changing musical world of the early seventeenth century. He knew only too well that singers required higher and higher levels of ability, since he himself was creating the new music that was making new demands on performers. As one anxious father noted, ‘there are so many musical compositions and the level of difficulty has reached the most difficult possible’, thus his daughter needed to be able to handle ‘with ease any song, no matter how weird or hard’. Now there was Francesca. Her voice, they said, spun ‘a finely focused thread of sound’. Not only that, but she had the musical intelligence to use that voice creatively, adding ‘dissonances’ that seemed to ‘offend’ but, paradoxically, like a lover mixing disdain with kindness, opened the way to a ‘more delightful path to harmonic sweetness’.

Giulio’s response to Francesca’s raw talent was to educate his daughter as if she did not belong to the artisan class into which he and she had been born. She studied Latin, rhetoric, poetics, geometry, astrology, philosophy, contemporary languages, ‘humanistic studies’ and even a little Greek. Crucially, she also learned composition, primarily to enhance her performances, since it was expected that singers should be able to improvise and, on occasion, perform their own song settings. Francesca’s progress was rapid. Just turned thirteen, on 9 October 1600 she was ready to appear in one of her father’s works, Il rapimento di Cefalo (The Abduction of Cephalus), alongside three, maybe four, other performing members of her family. It was the young Francesca’s first introduction to court spectacle: her stage, the Uffizi Palace in Florence; the occasion, the celebrations attending the proxy wedding of Henry IV of France and Marie de’ Medici; the audience, three thousand gentlemen and eight hundred ladies; the work, an opera lasting five hours; the cost, sixty thousand scudi, around three hundred years of salary for Francesca’s father.

Il rapimento provided a further lesson for the young Francesca, one in the politics of the music industry. Her father’s opera had been intended to be the primary spectacle of the Florentine 1600 winter season, but it was overshadowed by a work that had been performed just three days earlier at the Medici’s Pitti Palace: Jacobo Peri’s Euridice. Peri’s work has entered the music history books as the earliest opera for which complete music has survived, but, on the day, Peri quite simply judged his audience better than had Caccini. He not only gave the tragic story of Orpheus and Eurydice a happy ending, fitting for the happy occasion of Henry and Marie’s nuptials, but used to great effect a striking new technique, continuous recitatives between the set choral numbers.

Four years on, and Francesca’s breakthrough came when, in the summer of 1604, and the young singer approaching her seventeenth birthday, Henry IV and Marie de’ Medici, the royal couple for whom Giulio had written Il rapimento, asked the rulers of Tuscany if they could ‘borrow for several months’ Giulio’s ensemble ‘and his daughters’. And so it came to pass that Giulio, his second wife, two daughters, a son, a boy singing pupil, two carriages, six mules and 450 scudi (more than twice his annual salary) left the grand duchy on the last day of September 1604. They journeyed through the northern regions of a politically fractured land, for it would be more than 250 years until the first precarious unification of the Italian peninsula under one king. They stopped at Modena to sing for the ruling Este family; at Milan (controlled by the Spanish Habsburgs) because Francesca contracted malaria; then at Turin, where they performed for the Duke and Duchess of Savoy, and Francesca and her sister Settimia received gifts of jewellery. After just over two months of travelling, the Caccini family and entourage arrived in Paris on 6 December 1604 where they stayed with the resident Florentine ambassador – the happy recipients of kitchen privileges, firewood and wine. Giulio presented the time as the high point of his career, with visits from aristocrats, money available to ‘dress my women in French fashion’ and regular opportunities to perform for the French sovereigns.

The reality was slightly different, at least at first. Giulio’s arrogance made him few friends at the French court, and the monarchs themselves quarrelled over which of them would pay for the musicians. Everything changed, however, when Francesca sang. Henry IV declared her to be the best singer in France. It was reported that Queen Marie was so keen to secure Francesca for her own court that she was even willing to provide ‘the other’, Settimia, Francesca’s sister, with a dowry ‘enough that she could marry’. (The convention of the time was to provide both a job and a husband to women musicians.)

Yet no deal was done. Giulio gave the impression that the Grand-Duke of Tuscany himself had refused Caccini permission to accept the job for Francesca from Marie de’ Medici, but in fact he had his own agenda, writing that he had ‘invested’ much ‘labour’ in Francesca, and he did not want to lose his controlling interest, even to a French queen. Marie, in turn, gradually lost interest and the moment passed. Nevertheless, although Giulio was unwilling to admit it, a subtle shift in the balance of power between father and daughter occurred in Paris in the early months of 1605. He was now as much the father of ‘La Cecchina’ (little Francesca) as she was the daughter of the great Giulio Caccini.*

Francesca’s social and musical education continued apace. She knew about the precarious nature of a musician’s life from her own parents’ history. Her mother, Lucia, had been fired from her job as a musician only a year after Francesca’s birth, collateral damage from the arrival of the new duke, Ferdinando I, who wanted to purge his predecessor’s luxuries, or at least be seen to do so. Francesco I had been something of a text-book Medici villain, known to history as debauched and cruel if also scholarly and introverted, so it is unsurprising that Ferdinando wanted to make a break with the past. Did Francesca also know that, six months after Lucia’s death, her father lost his job in highly suggestive circumstances? A courtesan, known as ‘La Gambarella’, was having singing lessons with Giulio. Rumours began. La Gambarella’s lover, who was bank-rolling the lessons, had Giulio fired. The case did not help Giulio to recruit young female singers to his studio in Florence, and for a time his career stuttered horribly. One Duke Vincenzo, for example, wanted his protégée, Caterina Martinelli, to gain more experience, but not in Caccini’s house, the duke writing that Giulio ‘insisted on trying to make me understand that she would be safe, but I closed his mouth with a single word’. Martinelli went elsewhere.

The return journey to Tuscany provided a chance for Francesca to test out the effectiveness of her social, political and musical education. Whilst the rest of the Caccini family returned to Florence, Francesca, approaching eighteen, remained for six months at the Este court in Modena, where she taught Giulia d’Este, a couple of years her junior, to ‘sing in the French style’. There, Caccini applied all the lessons she had learned about how to survive (or not) the vagaries of high politics and sexual intrigue, and gained yet more insight into the workings of the elite families for whom she might one day work. The Este family did not want her to return to Florence.

Then came the carnival season of 1607. The Medici family, led by the Grand-Duchess, Christine de Lorraine, were at the time based in Pisa, and were planning a court spectacle. It needed to be impressive, but also cheap (perhaps costumes could be reused, suggests Christine) and to allow dancing amongst the cast and the guests. Christine turned to Michelangelo Buonarroti, great-nephew of the Michelangelo, who designed and scripted what would be the major entertainment for the carnival that year: a barriera, a dance representative of a battle. It was Michelangelo who chose Francesca Caccini, not yet twenty, to write the music. With the ‘advice and consent of her father’ Francesca seized the opportunity, not only producing her scores efficiently but creating ‘very beautiful’ music, in Michelangelo’s words.

We will never be able to judge for ourselves if Michelangelo was right, because, as with so many of Caccini’s works, the music has not survived. According to her contemporaries, however, La stiava (The Slavegirl) was more than beautiful; it was ‘una musica stupenda’. The performance began with a sinfonia ‘for many instruments’ during which the cast entered, and ended with a five-voice chorus to which both the cast and audience danced, as per the command of the work’s patron, Christine de Lorraine. Francesca embraced the new Florentine stile recitativo (now simply known as recitative), which had been championed by her own father, who, in the preface to his Le nuove musiche, praised its ability to make the singer ‘speak in music’ by employing a certain sprezzatura di canto. Sprezzatura, the hallmark of Renaissance sophistication, involved, in the words of its champion, the writer Castiglione, ‘a certain non-chalance, so as to conceal all art and make whatever one does or says appear to be without effort and almost without any thought about it’. To sing with sprezzatura one had to have the skill to make the performance effortless and natural. Father and daughter, both experts in precisely this skill, asserted the new style in direct competition with the music being composed by Venice’s musical avant-garde, led by that city’s star composer Monteverdi, but also in competition with their own colleagues in Florence, composers such as Jacobo Peri, who had se...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Notes from the silence

- 1 Caccini

- 2 Strozzi

- 3 Jacquet de la Guerre

- 4 Martines

- 5 Hensel

- 6 Schumann

- 7 Boulanger

- 8 Maconchy

- Endnote

- Further Listening

- Glossary

- Further Reading

- Works consulted

- Acknowledgements

- Index

- About the Author

- Imprint Page