eBook - ePub

What a Plant Knows

A Field Guide to the Senses of Your Garden - and Beyond

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A captivating journey into the inner lives of plants – from the colours they see to the schedules they keep

An enchanting look at the lives of plants, from the colours they see to the schedules they keep, in time for the start of the planting season

'An intriguing look at a plant's consciousness.' Scientific American

In What a Plant Knows, renowned biologist Daniel Chamovitz presents a beguiling exploration of how plants experience our shared Earth – in terms of sight, smell, touch, hearing, memory, and even awareness. Combining cutting-edge research with lively storytelling, he explains the intimate details of plant behaviour, from how a willow tree knows when its neighbours have been commandeered by an army of ravenous beetles to why an avocado ripens when you give it the company of a banana in a bag (it’s the pheromones).

Combining cutting-edge research with lively storytelling, biologist Daniel Chamovitz explores how plants experience our shared Earth – through sight, smell, touch, hearing, memory, and even awareness. Whether you are a green thumb, a science buff, a vegetarian, or simply a nature lover, this rare inside look at the life of plants will surprise and delight.

Discover:

An enchanting look at the lives of plants, from the colours they see to the schedules they keep, in time for the start of the planting season

'An intriguing look at a plant's consciousness.' Scientific American

In What a Plant Knows, renowned biologist Daniel Chamovitz presents a beguiling exploration of how plants experience our shared Earth – in terms of sight, smell, touch, hearing, memory, and even awareness. Combining cutting-edge research with lively storytelling, he explains the intimate details of plant behaviour, from how a willow tree knows when its neighbours have been commandeered by an army of ravenous beetles to why an avocado ripens when you give it the company of a banana in a bag (it’s the pheromones).

Combining cutting-edge research with lively storytelling, biologist Daniel Chamovitz explores how plants experience our shared Earth – through sight, smell, touch, hearing, memory, and even awareness. Whether you are a green thumb, a science buff, a vegetarian, or simply a nature lover, this rare inside look at the life of plants will surprise and delight.

Discover:

- How does a Venus flytrap know when to snap shut?

- Can an orchid get jet lag?

- Does a tomato plant feel pain when you pluck a fruit from its vines?

- And does your favourite fern care whether you play Bach or the Beatles?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What a Plant Knows by Daniel Chamovitz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

What a Plant Sees

She turns, always, towards the sun, though her roots hold her fast, and, altered, loves unaltered.

– Ovid, Metamorphoses

Think about this: plants see you.

In fact, plants monitor their visible environment all the time. Plants see if you come near them; they know when you stand over them. They even know if you’re wearing a blue or a red shirt. They know if you’ve painted your house or if you’ve moved their pots from one side of the living room to the other.

Of course plants don’t ‘see’ in pictures as you or I do. Plants can’t discern between a slightly balding middle-aged man with glasses and a smiling little girl with brown curls. But they do see light in many ways and colours that we can only imagine. Plants see the same ultraviolet light that gives us sunburn and infrared light that heats us up. Plants can tell when there’s very little light, like from a candle, or when it’s the middle of the day, or when the sun is about to set into the horizon. Plants know if the light is coming from the left, the right, or from above. They know if another plant has grown over them, blocking their light. And they know how long the lights have been on.

So, can this be considered ‘plant vision’? Let’s first examine what vision is for us. Imagine a person born blind, living in total darkness. Now imagine this person being given the ability to discriminate between light and shadow. This person could differentiate between night and day, inside and outside. These new senses would definitely be considered rudimentary sight and would enable new levels of function. Now imagine this person being able to discern colour. She can see blue above and green below. Of course this would be a welcome improvement over darkness or being able to discern only white or grey. I think we can all agree that this fundamental change – from total blindness to seeing colour – is definitely ‘vision’ for this person.

Merriam-Webster’s dictionary defines ‘sight’ as ‘the physical sense by which light stimuli received by the eye are interpreted by the brain and constructed into a representation of the position, shape, brightness, and usually colour of objects in space’. We see light in what we define as the ‘visual spectra’. Light is a common, understandable synonym for the electromagnetic waves in the visible spectrum. This means that light has properties shared with all other types of electrical signals, such as micro and radio waves. Radio waves for AM radio are very long, almost half a mile in length. That’s why radio antennas are many storeys tall. In contrast, X-ray waves are very, very short, one trillion times shorter than radio waves, which is why they pass so easily through our bodies.

Light waves are somewhere in the middle, between 0.0000004 and 0.0000007 metre long. Blue light is the shortest, while red light is the longest, with green, yellow, and orange in the middle. (That’s why the colour pattern of rainbows is always orientated in the same direction – from the colours with short waves, like blue, to the colours with long waves, like red.) These are the electromagnetic waves we ‘see’ because our eyes have special proteins called photoreceptors that know how to receive this energy, to absorb it, in the same way that an antenna absorbs radio waves.

The retina, the layer at the back of our eyeballs, is covered with rows and rows of these receptors, rather like the rows and rows of LEDs in flat-screen televisions or sensors in digital cameras. Each point on the retina has photoreceptors called rods, which are sensitive to all light, and photoreceptors called cones, which respond to different colours of light. Each cone or rod responds to the light focused on it. The human retina contains about 125 million rods and six million cones, all in an area about the size of a passport photo. That’s equivalent to a digital camera with a resolution of 130 megapixels. This huge number of receptors in such a small area gives us our high visual resolution. For comparison, the highest-resolution outdoor LED displays contain only about ten thousand LEDs per square metre, and common digital cameras have a resolution of about eight megapixels.

Rods are more sensitive to light and enable us to see at night and under low-light conditions but not in colour. Cones allow us to see different colours in bright light since cones come in three flavours – red, green, and blue. The major difference between these different photoreceptors is the specific chemical they contain. These chemicals, called rhodopsin in rods and photopsins in cones, have a specific structure that enables them to absorb light of different wavelengths. Blue light is absorbed by rhodopsin and the blue photopsin; red light by rhodopsin and the red photopsin. Purple light is absorbed by rhodopsin, blue photopsin, and red photopsin, but not green photopsin, and so on. Once the rod or cone absorbs the light, it sends a signal to the brain that processes all of the signals from the millions of photoreceptors into a single coherent picture.

Blindness results from defects at many stages: from light perception by the retina due to a physical problem in its structure; from the inability to sense the light, (because of problems in the rhodopsin and photopsins); or in the ability to transfer the information to the brain. People who are colour-blind for red, for example, don’t have any red cones. Thus the red signals are not absorbed and passed on to the brain. Human sight involves cells that absorb the light and the brain then processes this information, which we in turn respond to. So what happens in plants?

Darwin the Botanist

It’s not widely known that for the twenty years following his publication of the landmark On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin conducted a series of experiments that still influence research in plants to this day.

Darwin was fascinated by the effects of light on plant growth, as was his son Francis. In his final book, The Power of Movement in Plants, Darwin wrote: ‘There are extremely few [plants], of which some part ... does not bend towards lateral light.’ Or in less verbose modern English: almost all plants bend towards the light. We see that happen all the time in houseplants that bow and bend towards rays of sunshine coming in from the window. This behaviour is called phototropism. In 1864 a contemporary of Darwin’s, Julius von Sachs, discovered that blue light is the primary colour that induces phototropism in plants, while plants are generally blind to other colours that have little effect on their bending towards light. But no one knew at that time how or which part of a plant sees the light coming from a particular direction.

Canary grass (Phalaris canariensis)

In a very simple experiment, Darwin and his son showed that this bending was due not to photosynthesis, the process whereby plants turn light into energy, but rather to some inherent sensitivity to move towards the light. For their experiment, the two Darwins grew a pot of canary grass in a totally dark room for several days. Then they lit a very small gas lamp twelve feet (3.5 metres) from the pot and kept it so dim that they ‘could not see the seedlings themselves, nor see a pencil line on paper.’ But after only three hours, the plants had obviously curved towards the dim light. The curving always occurred at the same part of the young plant, an inch or so (about two centimetres) below the tip.

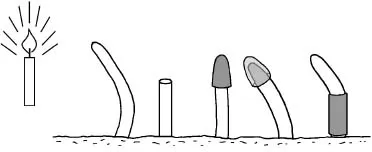

This led them to question which part of the plant saw the light. The Darwins carried out what has become a classic experiment in botany. They hypothesized that the ‘eyes’ of the plant were found at the seedling tip and not at the part of the seedling that bends. They checked phototropism in five different seedlings, illustrated by the following diagram:

Summary of Darwin’s experiments on phototropism

a. The first seedling was untreated and shows that the conditions of the experiment are conducive to phototropism.

b. The second had its tip pruned off.

c. The third had its tip covered with a lightproof cap.

d. The fourth had its tip covered with a clear glass cap.

e. The fifth had its middle section covered by a lightproof tube.

They carried out the experiment on these seedlings in the same conditions as their initial experiment, and of course the untreated seedling bent towards the light. Similarly, the seedling with the lightproof tube around its middle (see e above) bent towards the light. If they removed the tip of a seedling, however, or covered it with a lightproof cap, it went blind and couldn’t bend towards the light. Then they witnessed the behaviour of the plant in scenario four (d): this seedling continued to bend towards the light even though it had a cap on its tip. The difference here was that the cap was clear. The Darwins realized that the glass still allowed the light to shine onto the tip of the plant. In this one simple experiment, published in 1880, the two Darwins proved that phototropism is the result of light hitting the tip of a plant’s shoot, which sees the light and transfers this information to the plant’s midsection to tell it to bend in that direction. The Darwins had successfully demonstrated rudimentary sight in plants.

Maryland Mammoth:

The Tobacco That Just Kept Growing

Several decades later, a tobacco strain cropped up in the valleys of southern Maryland and reignited interest in the ways that plants see the world. These valleys have been home to some of America’s greatest tobacco farms since the first settlers arrived from Europe at the end of the seventeenth century. Tobacco farmers, learning from the native tribes such as the Susquehannock, who had grown tobacco for centuries, would plant their crop in the spring and harvest it in late summer. Some of the plants weren’t harvested for their leaves and made flowers that provided the seed for the next year’s crop. In 1906, farmers began to notice a new strain of tobacco that never seemed to stop growing. It could reach four and a half metres in height, produce almost a hundred leaves, and would only stop growing when the frosts set in. On the surface, such a robust, ever-growing plant would seem a boon to tobacco farmers. But as is so often the case, this new strain, aptly named Maryland Mammoth, was like the two-faced Roman god Janus. On the one hand, it never stopped growing; on the other, it rarely flowered, meaning farmers couldn’t harvest seed for the next year’s crop.

In 1918, Wightman W. Garner and Harry A. Allard, two scientists at the US Department of Agriculture, set out to determine why Maryland Mammoth didn’t know when to stop making leaves and start making flowers and seeds instead. They planted the Maryland Mammoth in pots and left one group outside in the fields. The other group was put in the field during the day but moved to a dark shed every afternoon. Simply limiting the amount of light the plants saw was enough to cause Maryland Mammoth to stop growing and start flowering. In other words, if Maryland Mammoth was exposed to the long days of summer, it would keep growing leaves. But if it experienced artificially shorter days, then it would flower.

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum)

This phenomenon, called photoperiodism, gave us the first strong evidence that plants measure how much light they take in. Other experiments over the years have revealed that many plants, just like the Mammoth, flower only if the day is short; they are referred to as ‘short-day’ plants. Such short-day plants include chrysanthemums and soybeans. Some plants need a long day to flower; irises and barley are considered ‘long-day’ plants. This discovery meant that farmers could now manipulate flowering to fit their schedules by controlling the light that a plant sees. It’s not surprising that farmers in Florida soon figured out that they could grow Maryland Mammoth for many months (without the effects of frost encountered in Maryland) and that the plants would eventually flower in the fields in midwinter when the days were the shortest.

What a Difference a (Short) Day Makes

The concept of photoperiodism sparked a rush of activity among scientists who were brimming with follow-up questions: Do plants measure the length of the day or the night? And what colour of light are plants seeing?

Around the time of World War II, scientists discovered that they could manipulate when plants flowered simply by quickly turning the lights on and off in the middle of the night. They could take a short-day plant like the soybean and keep it from making flowers in short days they turned on the lights for only a few minutes if in the middle of the night. On the other hand, the scientists could cause a long-day plant like the iris to make flowers even in the middle of the winter (during short days when it shouldn’t normally flower), if in the middle of the night they turned on the lights for just a few moments. These experiments proved that what a plant measures is not the length of the day but the length of the continuous period of darkness.

Using this technique, flower farmers can keep chrysanthemums from flowering until just before Mother’s Day, which is the optimal time to have them burst onto the spring flower scene. Chrysanthemum farmers have a problem since Mother’s Day comes in the spring but the flowers normally blossom in the autumn as the days get shorter. Fortunately, chrysanthemums grown in greenhouses can be kept from flowering by turning on the lights for a few minutes at night throughout the autumn and winter. Then ... boom ... two weeks before Mother’s Day, the farmers stop turning on the lights at night, and all the plants start to flower at once, ready for harvest and shipping.

These scientists were curious about the colour of light that the plants saw. What they discovered was surprising: the plants, and it didn’t matter which ones were tested, only responded to a flash of red during the night. Blue or green flashes during the night, wouldn’t influence when the plant flowered, but only a few seconds of red would. Plants were differentiating between colours: they were using blue light to know which direction to bend in and red light to measure the length of the night.

Then, in the early 1950s, Harry Borthwick and his colleagues in the US Department of Agriculture lab where Maryland Mammoth was first studied made the amazing discovery that far-red light – light that has wavelengths that are a bit longer than bright red and is most often seen, just barely, at dusk – could cancel the effect of the red light on plants. Let me spell this out more clearly: If you take irises, which normally don’t flower in long nights, and give them a shot of red light in the middle of the night, they’ll make flowers as bright and as beautiful as any iris in a nature reserve. But if you shine far-red light on them right after the pulse of red, it’s as if they never saw the red light to begin with. They won’t flower. If you then shine red light on them after the far-red, they will. Hit them again with far-red light, and they won’t. And so on. We’re also not talking about lots of light; a few seconds of either colour is enough. It’s like a light-activated switch: The red light turns on flowering; the far-red light turns it off. If you flip the switch back and forth fast enough, nothing happens. On a more philosoph...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Contents

- Prologue

- 1. What a Plant Sees

- 2. What a Plant Smells

- 3. What a Plant Feels

- 4. What a Plant Hears

- 5. How a Plant Knows Where It Is

- 6. What a Plant Remembers

- Epilogue: The Aware Plant

- Notes

- Acknowledgements

- Index

- Illustration Credits

- A Note About the Author