- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

We live in a world where the drive for economic growth is crowding out everything that can’t be given a monetary value. We’re stuck on a treadmill where only the material things in life gain traction and it’s getting harder to find space for the things that really matter but money can’t buy, including our future.

Fiona Reynolds proposes a solution that is at once radical and simple – to inspire us through the beauty of the world around us. Delving into our past, examining landscapes, nature, farming and urbanisation, she shows how ideas about beauty have arisen and evolved, been shaped by public policy, been knocked back and inched forward until they arrived lost in the economically-driven spirit of today. A passionate, polemical call to arms, The Fight for Beauty presents an alternative path forward: one that, if adopted, could take us all to a better future.

Fiona Reynolds proposes a solution that is at once radical and simple – to inspire us through the beauty of the world around us. Delving into our past, examining landscapes, nature, farming and urbanisation, she shows how ideas about beauty have arisen and evolved, been shaped by public policy, been knocked back and inched forward until they arrived lost in the economically-driven spirit of today. A passionate, polemical call to arms, The Fight for Beauty presents an alternative path forward: one that, if adopted, could take us all to a better future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Fight for Beauty by Fiona Reynolds in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Oneworld PublicationsYear

2016eBook ISBN

9781780748764Subtopic

Sustainable Development1

From admiration to defence

‘That is what you are doing with your scenery!’ With his paintbrush held aloft, John Ruskin, the writer, art historian and philosopher, shocked his audience by defacing a painting by his hero and national celebrity J. M. W. Turner. It was a landscape of Leicester Abbey, and across its glass frame he scrawled a monstrous iron bridge, a heavily polluted river and billowing smoke.

The only surviving account of this event, a lecture Ruskin gave at Oxford University, comes from a student who was present, the young A. E. Housman, who would go on to write one of the best-loved elegies to England, A Shropshire Lad. But for the moment, he and his fellow students were awed by the Slade Professor of Fine Art’s blatant confrontation of modern civilisation. ‘The atmosphere is supplied – thus!’ Ruskin continued, dashing a flame of scarlet across the picture, which became first bricks and then a chimney from which rushed a puff and cloud of smoke all over Turner’s sky. Housman describes how Ruskin threw down his brush amidst a tempest of applause, his students enthralled by the idea that beauty could matter as much, if not more, than the unconstrained pursuit of wealth.

Those were radical ideas in the 1870s, but support was building for Ruskin’s views. For as well as bringing great wealth and innovation, industrialisation was casting a pall over a nation whose countryside was internationally admired; whose poets, artists and writers were renowned for celebrating it; and whose identity was shaped by its beauty. The fight for beauty had begun, and Ruskin was at the heart of it.

The beauty of Britain’s nature and landscape has long captivated the people of this country and has taken many forms. Chaucer wrote lyrically of the countryside’s awakening in the spring as part of the inspiration for ‘folk to goon pilgrimages’; and mediaeval craftsmen painted and sculpted exquisite flowers, leaves and creatures into the friezes, pillars and gargoyles of cathedrals and country churches. As well as vivid descriptions of nature and landscape in his sonnets and plays, Shakespeare’s evocative settings – whether the leafy Warwickshire Forest of Arden or the bleakness of Macbeth’s Scottish hills – are central to the appreciation of his texts. Thomas Traherne, a century later (he was born in 1636), captures the religious underpinning of much appreciation of landscape and nature in Centuries of Meditation: ‘This visible World is wonderfully to be delighted in, and highly to be esteemed, because it is the theatre of God’s righteous kingdom.’

Beauty was a word freely used and invoked, whether by young men in search of Arcadia as they travelled the continent on the Grand Tour, educating and preparing themselves for their future lives, or by the many people inspired by the increasingly popular school of landscape painting, led by Thomas Gainsborough in England and Richard Wilson and Thomas Jones in Wales. Thomas Gray’s romantic 1719 ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’, celebrating the beauty of nature and everyday country life, reached unprecedented heights of popularity, becoming one of the most quoted poems of the English language.

The early eighteenth century was a time of burgeoning interest in aesthetics, and Edmund Burke, in his 1757 Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, drew a distinction between what was considered beautiful, derived from love or pleasure; and what was sublime, triggered by pain or terror. Burke presented the sublime and the beautiful as antithetical, with the sublime inspiring delight at terror perceived but avoided, emotions echoed in Daniel Defoe’s descriptions of Westmoreland [sic] in his Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain as ‘a country eminent only for being the wildest, most barren and frightful of any that I have passed over in England, or even in Wales itself’. Beauty, on the other hand, was triggered by the warmer emotions of love and sensuality, and it was clear that the human-created world could be made to replicate, in a milder form, and closer to home, the affirming power of nature.

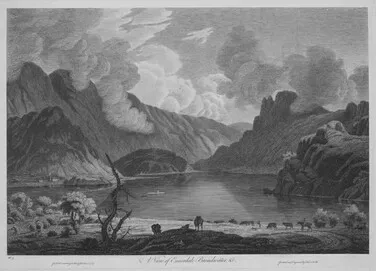

An engraving of the dramatic scenery that inspired thoughts of the sublime: Thomas Smith of Derby’s view of Ennerdale (© UK Government Art Collection).

The gentleman’s park, for instance, was a conscious attempt to enhance the natural landscape, sweeping away earlier manor houses and the structured form of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century gardens and replacing them with classical houses and ‘landscapes’ decorated with temples and monuments: expertly designed but natural-looking prospects which reconstructed the elements of ancient Arcadia in the countryside of Britain.

The person most in demand to create such idylls was ‘Capability’ Brown, the ‘omnipotent magician’ as William Cowper dubbed him after his death. Born in Northumberland, Brown trained under William Kent at Stowe, in Buckinghamshire, and went on to design or contribute to at least eighty landscape gardens in England. His wide, sweeping lawns with their perfectly placed serpentine lakes, and their neo-classical buildings carefully positioned to create an idealised view, represented the pinnacle of many eighteenth-century landowners’ aspirations. But he would have rebelled against the idea that his creations were entirely artificial. He was inspired by Alexander Pope’s instruction that landscape design should draw on the underlying ‘genius of the place’, a concept which shapes much thinking about landscape to this day:

Consult the Genius of the Place in all;

That tells the Waters or to rise, or fall;

Or helps th’ ambitious Hill the heav’ns to scale,

Or scoops in circling theatres the Vale;

Calls in the Country, catches op’ning glades,

Joins willing woods, and varies shades from shades;

Now breaks or now directs, th’ intending Lines;

Paints as you plant, and, as you work, designs.

(Alexander Pope, ‘Epistle IV’, addressed

to Lord Burlington, Moral Essays, 1731)

By the end of the eighteenth century tastes were changing and new ideas about beauty were emerging, favouring the countryside’s own qualities rather than those which were imposed upon it. William Gilpin, priest, artist and schoolmaster, proposed the ‘picturesque’ as something of a third way between the sublime and the beautiful, reflecting the naturalistic character of the British countryside, created without apparently conscious intervention: ‘Picturesque beauty is a phrase but little understood. We precisely mean by it that kind of beauty which would look well in a picture. Neither grounds laid out by art nor improved by agriculture are of this kind.’

In the 1760s Gilpin published accounts of his visits to the Lake District and the Wye Valley, prompting thousands of eager tourists who were drawn by his descriptions to explore the picturesque beauty of England’s countryside. Of the ancient trees of the New Forest he wrote: ‘Such Dryads! Extending their taper arms to each other, sometimes in elegant mazes along the plain; sometimes in single figures; and sometimes combined.’ Many followed his lead, clutching their sketchbooks and Claude glasses to frame the perfect view. His cause was taken up by Uvedale Price, a Herefordshire squire, who praised the ‘real’ countryside as a work of art, and also Humphry Repton, with whom he travelled down the Wye, because he (Repton) ‘really admired the banks in their natural state, and did not desire to turf them, or remove the large stones’. And as the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars restricted continental travel, enthusiasm for the landscapes of Britain was re-energised.

By the end of the eighteenth century the whole population could be said to be falling in love with nature and the British landscape. In addition to the tourists following Gilpin’s scenic routes, Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne and Thomas Bewick’s History of British Birds inspired a new generation of nature lovers. White’s finely observed, unsentimental prose described, named and publicised many species for the first time; and Bewick’s beautiful engravings formed a popular and widely used reference book, encouraging the fashion for bird identification. As the eighteenth century gave way to the nineteenth, the Romantic poets inspired a new generation of landscape and nature lovers, their outpourings devoured by a nation hungry to appreciate their pastoral, beautiful imagery of England.

And this was no superficial appreciation: William Wordsworth’s ‘Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey’ (1798) enjoin us not only to appreciate nature but to accept its moral depths:

to recognise

In nature and the language of the sense,

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being.

Wordsworth also brought something new. He had been born in Cockermouth in the Lake District in 1770 and grew up with a deep love of nature, travelling widely in France, Switzerland and Germany before settling again in his childhood home. By the time he published, in 1810, his best-selling Guide through the District of the Lakes he was tapping into a population hungry for the appreciation of its own countryside. He gave people routes and viewpoints, places to stay and sights to see. And his statement that the Lake District was ‘a sort of national property in which every man has a right and interest who has an eye to perceive and a heart to enjoy’ hinted at a universal stake in its landscape. Because while his predecessors as writers and poets had helped the nation to love nature, Wordsworth’s readers got something more. This revered place, his beloved Lake District, was coming under threat, and the stage was set for the first great clash about beauty. Admiration was about to tip into defence, and Wordsworth’s was the voice that brought this about.

William Wordsworth, whose passion for the Lake District tipped admiration of its beauty into defence.

During the early nineteenth century a new breed of business opportunists spotted the commercial potential of the age-old industries of the Lake District: slate quarrying, and mining for copper and other valuable minerals. They also wanted stylish places to live in the Lake District’s beautiful valleys. Wordsworth, whose passion for long, solitary walks meant that he knew the Lakes intimately, was among the first to raise the alarm, speaking out in his Guide against the construction of ugly villas in its beautiful valleys. In 1844 he fired off eloquent letters to The Morning Post objecting to a railway line that might link Kendal to Windermere and spoil for ever the solitude of a wilderness ‘rich with liberty’. In the same year he wrote the sonnet with which his passion for the Lake District has been ever since associated:

Is then no nook of English ground secure

From rash assault? Schemes of retirement sown

In youth, and ’mid the busy world kept pure

As when their earliest flowers...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Imprint Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 From admiration to defence

- 2 The calls and claims of natural beauty

- 3 National Parks – a nobler vision for a better world

- 4 How nature and the wider countryside lost out

- 5 How farming made and destroyed beauty

- 6 The curious case of trees

- 7 The coast – a success story

- 8 Cultural heritage – how caring for the past creates a better future

- 9 Urbanisation and why good planning matters

- 10 The case for beauty

- Acknowledgements

- Image Section

- Bibliography and further reading

- Index