- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

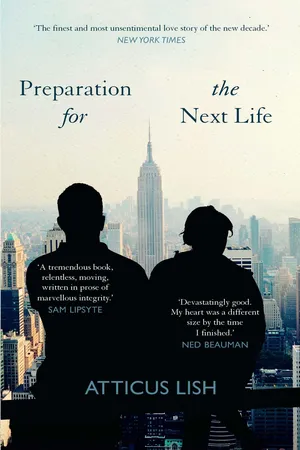

'BLISTERING' THE TIMES * 'EXTRAORDINARY' FINANCIAL TIMES

WINNER OF THE 2015 PEN/FAULKNER AWARD FOR FICTION

SOON TO BE A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE DIRECTED BY ACADEMY AWARD NOMINEE BING LIU

A gut-wrenching love story set in the underbelly of New York, about the unexpected connection between an illegal Uyghur migrant and a damaged Iraq veteran.

*Winner of the New York City Book Award for Fiction*

*Finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award for Fiction*

Set in the underbelly of New York, Preparation for the Next Life exposes an America as seen from the fringes of society and, in devastating detail, destroys the myth of the American Dream through two of the most remarkable characters in contemporary fiction. Powerful, realistic and raw, this is one of the most ambitious – and necessary – novels of our time.

New York Times Best of 2014

Wall Street Journal's Best of 2014

Vanity Fair's Best of 2014

Publishers Weekly's Best of 2014

BuzzFeed's Best of 2014

New York Times 100 Notable Books of 2015

WINNER OF THE 2015 PEN/FAULKNER AWARD FOR FICTION

SOON TO BE A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE DIRECTED BY ACADEMY AWARD NOMINEE BING LIU

A gut-wrenching love story set in the underbelly of New York, about the unexpected connection between an illegal Uyghur migrant and a damaged Iraq veteran.

*Winner of the New York City Book Award for Fiction*

*Finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award for Fiction*

Set in the underbelly of New York, Preparation for the Next Life exposes an America as seen from the fringes of society and, in devastating detail, destroys the myth of the American Dream through two of the most remarkable characters in contemporary fiction. Powerful, realistic and raw, this is one of the most ambitious – and necessary – novels of our time.

New York Times Best of 2014

Wall Street Journal's Best of 2014

Vanity Fair's Best of 2014

Publishers Weekly's Best of 2014

BuzzFeed's Best of 2014

New York Times 100 Notable Books of 2015

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Preparation for the Next Life by Atticus Lish in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

SHE CAME BY WAY of Archer, Bridgeport, Nanuet, worked off 95 in jeans and a denim jacket, carrying a plastic bag and shower shoes, a phone number, waiting beneath an underpass, the potato chips long gone, lightheaded.

They picked her up on the highway by a plain white shed, a sign for army-navy, tires in the trees. A Caravan pulled up with a Monkey King on the dash and she got in. The men took her to a Motel 8 and put her in a room with half a dozen other women from Fookien and a liter of orange soda. She listened to the trucks coming in all night and the AC running.

They gave her a shirt with an insignia and a visor, the smell of vaporized grease in the fabric. Everyone told her you have to be fast because the bossie watching you. They didn’t speak each other’s dialects, so they spoke English instead. Her first day, her worn-out sneakers slipped on the grease. She dropped an order, noodles popping out like worms, and that night she lay with her face to the wall, her jaw set, blinking.

The Americans parked out front, their pickups ticking in the sun, and came in slow and quiet in bandanas and tank tops. They would lean an elbow on the counter and point a thick finger at the menu and say that one there. The blacks came in holding what they were going to spend in their hands, the wadded dollars and change.

Is y’all gonna let me have them wings? Y’all tell me what I can get with this then.

She knew how to say okay. When they pointed at the menu, she got it fine. In Nanuet, they wanted the all-you-can-eat. She could understand that. You need to get some more of this. Okay. She knew how to hurry up and get something, to work because she had to, to work fourteen hours a day every day until the tenth or eleventh day, until they got a smoking day, as the boss called it, because it was better than picking through the trash in the brigade field south of the river.

In the motel, they kept the TV running to practice English. They squatted on the carpet, moving their mouths in the blue light, seeing the grocery store aisles and the fast cars. Unbelievable, they said. This Tuesday on Fox. A grim day in Iraq. She watched goggled soldiers and radio antennas driving past adobe houses in the desert, which she had lived in.

Camel, she pointed. The animal, it’s very good.

Too hard, they said. It can’t be absorbed. Mind is a wooden plank.

Someone yawned.

Have to practice it a lifetime.

When they had finished their work at night, they crossed the parking lot to the one car still there, the Caravan waiting to take them back to the motel. They gave the man his takeout, and he put it on the newspapers open to Hong Kong stories. She watched the large sweeps of the night go by as they drove home, the black areas of the forest, the slate highway and sky. He had a gold chain and a green card and he drove with the lights off, watching for cops.

The women were from Begin to Celebrate, Four Meetings, Connected Mountain, and Honesty Admired. She told them she was from south of the river.

But you’re from somewhere else, they said.

I’m Chinese, like you.

You don’t look it.

In the sun, you could see Zou Lei’s hair was brown and not black. There was a waviness to it. She had a slightly hooked nose and Siberian eyes.

Our China is a big country, she said.

You sound like a northerner.

Northwesterner.

She’s a minority, one of the women said. You can teach me your language.

That’s meaningless. You’ve got People’s Terrace, Peaceful Stream, Placid Lake, Winding South, Cotton Fence, Zhangpu, Convergence of Peace, Swatow, Common Tranquility, Prominence, Samyap, Jungcan, Broad Peace, Three Counties, Next-to-the-Zhang-Family Dialect, and a hundred more. Which one we teach you?

Zou Lei thought for a moment. Then tell me how to say heaven is high. She smiled and pointed at the stained ceiling. Heaven is high and the earth is wide.

Some of them nodded, a few smiled, revealing bad teeth. That’s true, that’s true, they agreed, and one of the women sighed.

What she learned instead was how to take an order. The fortune cookies were in the box under the Year-of-the-Goat calendar and the little plastic shrine. The napkins, straws, and chopsticks were all together on the shelf. Give everybody plastic fork no matter what. When a customer came in, you asked him what you having? Then you shout his order in the back: chick-brocc, beef-brocc, beef-snow, triple steam, like that, to make it fast.

No one had to teach her how to mop and take the trash out and go through a sack of greens, chopping off the part you didn’t eat. They saw she was a hard worker. Most of what you did was something she already knew. Squatting, she washed her clothes in the bathtub, wringing them out with her chapped, rural, purple-skinned hands, and hanging them up on the shower curtain rod with the others’ dripping laundry, the wet sequined denim and faded cartoon characters.

At the counter, she put a piece of cardboard in the bottom of a bag, stapled the lips of a Styrofoam shell together, and set the shell in the bag on top of the cardboard. The other containers went on top with cardboard in between. She stapled the menu to the bag and handed it over the counter to a lean guy in a red baseball hat and long blond hair. Taking an extra menu, he said, You’re gettin a whole lot better. I timed you.

The boss said the women needed someone to supervise their well-being, a big sister who would report to him. He gave them a phrase to memorize—It’s not a matter of time, it’s a matter of money—that he wanted them to repeat a thousand times a day as fast as they could say it.

What does it mean? she asked.

It is not significant. Its significance is unknown.

One of the women was mentally imbalanced, given to bouts of silence, and then saying the police had given her a forced abortion in Guangxi.

When the weather turned cold, some of them slept together. They squatted in front of the space heater, their wet clothes hanging in the shower, all of them sick, coughing and spitting up in the wastebasket.

On TV, she saw girls surfing, driving trucks, boxing, and marathoning in the sun. When deliveries came in, she ran outside and carried the sacks of rice in on her shoulder. The women disapproved, saying let the men do that, the cook and his cousin. Don’t go licking the boss’s piles. Zou Lei told them that she liked to move her legs. At night, she did sit-ups. She took a paper from the van and read the classified ads for jobs in other states.

She left for Riverhead and worked the rest of the winter there, staying in a La Quinta with a group of women who spoke Three Lights and country Mandarin. They had a hotplate, which they shared.

America is a good country, an older woman said. We took a fishing boat across the ocean. The ocean police caught us and closed us up on an island near San Francisco. I almost died on the voyage and that was what saved me. That was lucky. The others were forced back home, thirty people, but not me. My cousin applied me for asylum. Some of these other sisters have been deported once already. Now they come back, once becomes twice, twice becomes three times. They go to the Yucatan Peninsula, cross the border in Arizona. Now that’s hard, of course. That’s the desert, not for us people, river people. My village language is Watergrass. We’re fifty kilometers from Old Field and they don’t know a word we’re saying.

She spent a year in Archer and six months in Riverhead. Swine-flu season was over and the World News was carrying stories about the war on terror and the difficulty of getting a green card. She turned the page and saw a photograph in black and white of a naked prisoner lying on the ground with a sandbag on his head. She turned the page again, studying the words: construction, seamstress, restaurant, beauty, pay depends on ability.

She went to Nanuet and got another shirt with an insignia and another visor. The women lived in a trailer on cinder blocks, which rested on pine needles, and hung their washing on a line. On their smoking day, she hiked up to the mall, running across the highway and hopping the divider, and looked through the glass at the sneakers made in China.

The boss wore a jade bracelet and drove a dirty Astrovan. He had Zou Lei wash it out back where there were loading docks and dumpsters, a fence, and then the woods. She let the hose run, gazing past the dumpsters, and imagined herself running through the woods.

The next year, in another state, she was in a motel room with eight women who talked in code even in their own dialect. When she asked what village they were from, one of them said, Cinnamontree. The others turned on the woman who had talked and said, What are you doing telling secrets to an outsider?

They had a big sister called Sophia who determined when they could watch TV. They weren’t allowed to open the door when someone knocked unless Sophia was there and said it was okay.

In the women’s rhyming slang, Zou Lei eventually realized that a sailboat meant money that they were sending back to China. A shout was a phone, a crow was an illegal alien, and Andy meant the police.

A man arrived in mirrored shades with a dragon on his wrist, bringing them a pack of Stayfree. The boss loved music, he said. Everything I do, I do it for you. You know the song?

Once, when Sophia wasn’t there, Zou Lei let the maid into the room and asked her where she was from and what her job was like.

Honduras, the maid said, a tattoo of a cross on her hand. They were about the same age.

Zou Lei ran into the bathroom and came out with the wet towels in her arms and put them in the hamper. The Honduran girl smiled and said gracias.

How about you job, is the job money? Zou Lei asked.

No, no much money. Poquito money. You has working papers?

Zou Lei said, Take a guess. You think so?

No. They both laughed.

Maria taught her a handshake. Zou Lei showed her the ad in the Sing Tao where it said you could buy a social security number.

By knocking on a steel door, she found a job working eight-hour days putting clutch plates in cardboard boxes, the best money she had ever made: $9 an hour minus taxes. At lunchtime, she ate rice and turkey from a Tupperware container, while the Americans in Dickies and bandanas lined up at the lunch truck. She carried all her money with her all the time, clipped around her waist, cell phone, fake ID, the things she couldn’t lose.

One day in mid-autumn, she went into a bodega and got caught coming out the door.

Just relax. Do you have anything in your pockets? Anything sharp? It’s okay. Just relax. A Spanish guy in a football jersey lifted up her arms, looking past her as he turned her pockets inside out. He unclipped the belly bag from around her waist and handed it to a guy with a pistol half-hidden by his sweatshirt. She had just cashed her check inside the bodega and she followed the bag with her eyes. Do you need a translator? I feel your heart pounding in there. Just cálmate. Tranquilo, okay? You speak Spanish? What are you, Chinita? Chinese?

Why I didn’t run?

They felt through her clothes and took her money, zip-tied her, and put her in a van with a Salvadoran prisoner. It took all afternoon. Hey, mama, you shy? They had Fookienese, Cambodians, men from Guatemala. She was taken into a glass tank with a stainless steel bench and a cement floor and the fluorescent lights on, and other girls kept coming in and out all night, until they moved her. She rubbed the dents on her wrists made by the restraints.

A white girl with mascara down her cheeks said, These niggas better let me out for my boy’s birthday.

In the middle of the night, t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Part 1

- Part 2

- Part 3

- Epilogue