![]()

1

Introduction

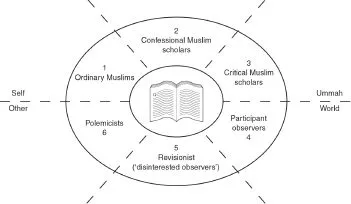

Muslims have often expressed their experience of the Qur’an in an array of metaphors. It has, for example, been compared to Damascus brocade: “The patterned beauty of its true design bears an underside which the unwary may mistake, seeing what is there, but not its real fullness. Or the Book is like a veiled bride whose hidden face is only known in the intimacy of truth’s consummation. It is like the pearl for which the diver must plunge to break the shell which both ensures and conceals treasure” (Cragg, 1988, 14). The late Fazlur Rahman (d. 1988) also used the analogy of a country, using the categories of “citizens”, “foreigners” and “invaders”, to describe some of the approaches of scholars towards the Qur’an (1984, 81). I want to latch on to the theme of beauty to provide an overview of approaches to the Qur’an and Qur’anic scholarship. Without in any way wanting to pre-empt the discussion on the worldly nature of the Qur’an, in reflecting on the diverse scholarly approaches to the Qur’an, I draw an analogy with the personality and body of a beloved and the ways in which she is approached. The body that comes to mind immediately is a female one and this itself is remarkable for what it reveals as much as what it conceals. The female body is usually presented and viewed as passive, and more often objectified as “something” to be approached even when it is alive, and “ornamentalized” as a substitute for enabling it to exercise real power in a patriarchal world. Yet this body or person also does something to the one that approaches it. The fact that it is approached essentially by men also reflects the world of Qur’anic scholarship, one wherein males are, by and large, the only significant players. When the female body is approached by other women then it is a matter to be passed over in silence. Like the world of religion in general, in which women play such a key part and yet, when it comes to authority and public representation, they are on the periphery, Qur’anic scholarship is really the domain of men; the contribution of women, when it does occur, is usually ignored. I understand and acknowledge that my analogy fits into many patriarchal stereotypes. Questions such as: “Why does the Qur’an not lend itself to being made analogous with a male body?” “What if a gender sensitive scholar insists on doing this, and how would my analogy then pan out?” “What about multiple partners in a post-modernist age where one finds Buddhist Catholics or Christian Pagans?” etc., are interesting ones which shall be left unexplored. Like all analogies, mine can also be taken too far and can be misleading in more than one respect.

The uncritical lover

The first level of interaction1 with the Qur’an can be compared to that between an uncritical lover and his beloved. The presence and beauty of the beloved can transport the lover to another plane of being that enables him to experience sublime ecstasy, to forget his woes, or to respond to them. It can console his aching heart and can represent stability and certainty in a rather stormy world: she is everything. The lover is often astounded at a question that others may ask: “What do you see in her?” “What do you mean? I see everything in her; she is the answer to all my needs. Is she not ‘a clarification of all things’ (16.89), ‘a cure for all [the aches] that may be in the hearts’ (10.57)? To be with her is to be in the presence of the Divine.” For most lovers it is perfectly adequate to enjoy the relationship without asking any questions about it. When coming from the outside, questions about the nature of the beloved’s body, whether she really comes from a distinguished lineage – begotten beyond the world of flesh and blood and born in the “Mother of Cities” (42.7) – as common wisdom has it, or whether her jewelery is genuine, will in all likelihood be viewed as churlishness or jealousy. For the unsophisticated yet ardent lover such questions are at best seen as a distraction from getting on with a relationship that is to be enjoyed rather than interrogated or agonized over. At worst, they are viewed as a reflection of willful perversity and intransigence. This lover reflects the position of the ordinary Muslim towards the Qur’an, a relationship discussed in greater detail in the second chapter.

Approaching the Qur’an.

The scholarly lover

The second level of interaction is that of a lover who wants to explain to the world why his beloved is the most sublime, a true gift from God that cries out for universal acclaim and acceptance. He goes into considerable detail about the virtues of his beloved, her unblemished origins and her delectable nature. This pious yet scholarly lover literally weeps at the inability of others to recognize the utter beyondness of his beloved’s beauty, the coherence of her form and the awe-inspiring nature of her wisdom. “She is unique in her perfection, surely it is sheer blindness, jealousy and (or) ignorance that prevents others from recognizing this!” This is the path of confessional Muslim scholarship based on prior faith that the Qur’an is the absolute word of God. Some of the major contemporary works2 that have emerged from these scholars include the exegeses of Abu’l ‘Ala Mawdudi (d. 1977),3 Amin Ahsan Islahi (d. 1997),4 Husayn Tabataba’i (d. 1981),5 and Muhammad Asad (d. 1992),6 ‘Aishah ‘Abd al-Rahman (Bint al-Shati),7 and the work on Qur’anic studies by Muhammad Husayn al-Dhahabi,8 Muhammad ‘Abd al-‘Azim al-Zarqani,9 (both contemporary Egyptian scholars), and Abu’l Qasim al-Khu’i (d. 1992).10 Others have written about specific aspects of the beloved’s beauty, the finery of her speech or the depth of her wisdom. In addition to the world of books, the other relatively new domain of some of the lovers in this category is the internet, where a large number of Muslim researchers, often autodidacts, engage in vigorous combat with all those who challenge the divine nature of the Qur’an.11 In depicting the positions of the scholars in this category, I have, in the main, utilized the works of earlier Cairene scholars such as Badr al-Din Zarkashi (d. 794/1391) and Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti (d. 911/1505), and among the contemporary ones, Zarqani and Al-Khu’i.

The critical lover

The third kind of lover may also be enamored with his beloved but will view questions about her nature and origins, her language, or if her hair has been dyed or nails varnished, etc., as reflecting a deeper love and more profound commitment, a love and commitment that will not only withstand all these questions and the uncomfortable answers that rigorous enquiry may yield, but that will actually be deepened by them. Alternatively, this relationship may be the product of an arranged marriage where he may simply never have known any other beloved besides this one and his scholarly interest moves him to ask these questions. As for the Qur’an being the word of God, his response would probably be “Yes, but it depends on what one means by ‘the word of God’. She may be divine, but the only way in which I can relate to her is as a human being. She has become flesh and I cannot interrogate her divine origins; I can therefore only approach her as if she is a worldly creature.” (“The study of the text”, says Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd, “must proceed from reality and culture as empirical givens. From these givens we arrive at a scientific understanding of the phenomenon of the text” (1993, 27).) This is the path of critical Muslim scholarship, a category that may be in conversation with the preceding two categories – as well as the subsequent two categories – but does not usually sit too well with them. What cannot be disputed is the devotion of this lover to his beloved. The anger with the objectification of the beloved by the first two categories, in fact, stems from an outrage that the “real” worth of the beloved is unrecognized. “My world is in a mess,” says this lover. “I cannot possibly hold on to you just for your ornamental or aesthetic value; I know that you are capable of much more than this!” As Abu Zayd asks, “How much is not concealed by confining the Qur’an to prayers and laws? ... We transform the Qur’an into a text which evokes erotic desire or intimidates. With root and branch do I want to remove the Qur’an from this prison so that it can once again be productive for the essence of culture and the arts in our society” (1994, 27). Some of the major works by these scholars include the exegetical work of Fazlur Rahman (d. 1988),12 the linguistic-philosophical studies by Mohammed Arkoun,13 the literary enquiry into the Qur’an and critique of religious discourse by Abu Zayd,14 and the related literary studies done by Fuat Sezgin.15

The friend of the lover

The line between the last of the categories above, the critical lover, and the first below, the participant observer, is often a thin one. In the same way that one is sometimes moved to wonder about couples: “Are they still in love or are they just sticking to each other for old time’s sake?”, one can also ask about one’s intimate friends who display an unusual amount of affection to one’s own beloved: “What’s up here?” In other words, is the critical lover really still a lover, and is the ardent friend of both the lover and the beloved not perhaps also a lover? Similarly, questions have been raised about the extent to which the participant observer has internalized Muslim sensitivities and written about the Qur’an in a manner that sometimes makes one wonder if they are not also actually in love with the Muslim’s beloved. Thus what these two categories have in common is that those at the other ends of the continuum really accuse them of being closet non-Muslims or closet Muslims.

The participant observer, the first in the category of those who do not claim to be lovers or who deny it, feels an enormous sense of responsibility to the sensitivities of the lover, who is often also a close friend of lover and beloved. “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” he reasons, “and if this is what the Qur’an means for Muslims and if they have received it as the word of God, then so be it. We don’t know if Gabriel really communicated to Muhammad and we will never know. What we do know is that the Qur’an has been and continues to be received by the Muslims as such. Can we keep open the question of ‘whatever else it may be’ and study it as received scripture which is also an historical phenomenon?” Wilfred Cantwell Smith (1980) who places more emphasis on the spiritual dimensions of this reception – in contrast to Montgomery Watt who emphasizes its sociological dimensions – is arguably the most prominent scholar who adopts this position.16 “Given that it was first transmitted in an oral form,” asks William Graham further, “can we focus on the Qur’an as an oral scripture rather than written text?”17 Others in this category may have their own objects of adoration and love but acknowledge the beauty of the Muslim’s beloved. They can possibly also love her, although in a different sense, but would be hesitant to declare this love for fear of being misunderstood. (“I have always taken the view that Muhammad genuinely believed that the messages he received – which constitute the Qur’an – came from God. I hesitated for a time to speak of Muhammad as a Prophet because this would have been misunderstood by Muslims ...”; Watt, 1994, 3.)18 Another scholar in the genre whose work I have found inspiring is Kenneth Cragg, the Oxford-based Anglican clergyman whom Rahman has described as “a man who may not be a full citizen of the world of the Qur’an, but is certainly no foreigner either – let alone an invader!” (1984, 81).19 This irenic approach to the study of the Qur’an seemingly seeks to compensate for past “scholarly injuries” inflicted upon Muslims and is often aimed at a “greater appreciation of Islamic religiousness and the fostering of a new attitude towards it” (Adams, 1976, 40). This category of scholar accepts the broad outlines of Muslim historiography and of claims about the development of the Qur’an. While the first two categories – the “ordinary Muslim” and confessional scholar, the latter being increasingly aware of their presence – find them annoying or even reprehensible, they are often in vigorous and mutually enriching conversation with the third category, the critical Muslim scholar.

The voyeur

The second observer in this category feels no such responsibility and claims that he is merely pursuing the cold facts surrounding the body of the beloved, regardless of what she may mean to her lover or anyone else. He claims, in fact, to be a “disinterested” observer (Rippin, 2001, 154). Willing to challenge all the parameters of the received “wisdom”, he may even suggest that the idea of a homogenous community called “Muslims” which emerged over a period of 23 years in Arabia is a dubious one – to put it mildly. The beloved, according to him, has no unblemished Arab pedigree, less still is she “begotten-not-created”. Instead, she is either “the illegitimate off-spring of Jewish parents” (“The core of the Prophet’s message ... appears as Judaic messianism” [Crone and Cook, 1977, 4]); or of Jewish and Christian parents (“The content of the Qur’an ... consists almost exclusively of elements adapted from the Judeo-Christian tradition” [Wansbrough, 1977, 74]). These scholars view the whole body of Muslim literature on Islamic history as part of its Salvation History which “is not an historical account of saving events open to the study of the historian; salvation history did not happen; it is a literary form which has its own historical context ... and must be approached by means appropriate to such; literary analysis” (Rippin, 2001, 155). Based on this kind of analysis, the work of John Wansbrough (1977),20 Andrew Rippin (who has done a good bit to make Wansbrough’s terse, technical, and even obtuse writing accessible) and the more recent work by a scholar writing under the name of “Christoph Luxenberg” (2000),21 seek to prove that the early period of Islam shows “a great deal of flexibility in Muslim attitudes towards the text and a slow evolution towards uniformity ... which did not reach its climax until the fourth Islamic century” (Encyclopedia of Religion, see “Qur’an”). While some of these scholars, often referred to as “revisionists”, have insisted on a literary approach to the Qur’an, their views are closely connected to the idea of Muslim history as essentially a product of a Judeo-Christian milieu, argued by Patricia Crone (1977) and Michael Cook (Crone and Cook, 1977 and Cook, 1981), two other scholars whose contribution to revisionist thinking is immeasurable.22 The basic premise of this group of scholars is the indispensability of a source critical approach to both the Qur’an and Muslim accounts of its beginning, the need to compare these accounts with others external to Muslim sources, and utilizing contemporary material evidence including those deriving from epigraphy, archaeology, and numismatics.

Needless to say, this approach, a kind of voyeurism, and its putative disintereste...