- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

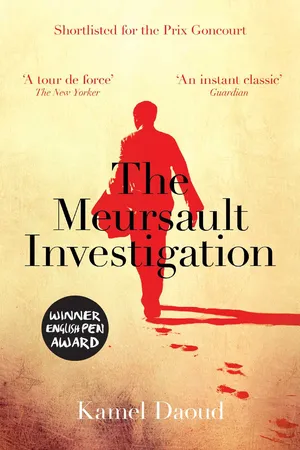

The Meursault Investigation

About this book

Shortlisted for the Prix Goncourt

Winner of the Goncourt du Premier Roman

Winner of the Prix des Cinq Continents

Winner of the Prix François Mauriac

THE NOVEL THAT HAS TAKEN THE INTERNATIONAL LITERARY WORLD BY STORM

He was the brother of ‘the Arab’ killed by the infamous Meursault, the antihero of Camus’s classic novel. Angry at the world and his own unending solitude, he resolves to bring his brother out of obscurity by giving him a name – Musa – and a voice, and by describing the events that led to his senseless murder on a dazzling Algerian beach. A worthy complement to its great predecessor, The Meursault Investigation is not only a profound meditation on Arab identity and the disastrous effects of colonialism in Algeria, but also a stunning work of literature in its own right, told in a unique and affecting voice.

Winner of the Goncourt du Premier Roman

Winner of the Prix des Cinq Continents

Winner of the Prix François Mauriac

THE NOVEL THAT HAS TAKEN THE INTERNATIONAL LITERARY WORLD BY STORM

He was the brother of ‘the Arab’ killed by the infamous Meursault, the antihero of Camus’s classic novel. Angry at the world and his own unending solitude, he resolves to bring his brother out of obscurity by giving him a name – Musa – and a voice, and by describing the events that led to his senseless murder on a dazzling Algerian beach. A worthy complement to its great predecessor, The Meursault Investigation is not only a profound meditation on Arab identity and the disastrous effects of colonialism in Algeria, but also a stunning work of literature in its own right, told in a unique and affecting voice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Meursault Investigation by Kamel Daoud, John Cullen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Mama’s still alive today.

She doesn’t say anything now, but there are many tales she could tell. Unlike me: I’ve rehashed this story in my head so often, I almost can’t remember it anymore.

I mean, it goes back more than half a century. It happened, and everyone talked about it. People still do, but they mention only one dead man, they feel no compunction about doing that, even though there were two of them, two dead men. Yes, two. Why does the other one get left out? Well, the original guy was such a good storyteller, he managed to make people forget his crime, whereas the other one was a poor illiterate God created apparently for the sole purpose of taking a bullet and returning to dust — an anonymous person who didn’t even have the time to be given a name.

I’ll tell you this up front: The other dead man, the murder victim, was my brother. There’s nothing left of him. There’s only me, left to speak in his place, sitting in this bar, waiting for condolences no one’s ever going to offer. Laugh if you want, but this is more or less my mission: I peddle offstage silence, trying to sell my story while the theater empties out. As a matter of fact, that’s the reason why I’ve learned to speak this language, and to write it too: so I can speak in the place of a dead man, so I can finish his sentences for him. The murderer got famous, and his story’s too well written for me to get any ideas about imitating him. He wrote in his own language. Therefore I’m going to do what was done in this country after Independence: I’m going to take the stones from the old houses the colonists left behind, remove them one by one, and build my own house, my own language. The murderer’s words and expressions are my unclaimed goods. Besides, the country’s littered with words that don’t belong to anyone anymore. You see them on the façades of old stores, in yellowing books, on people’s faces, or transformed by the strange creole decolonization produces.

So it’s been quite some time since the murderer died, and much too long since my brother ceased to exist for everyone but me. I know, you’re eager to ask the type of questions I hate, but please listen to me instead, please give me your attention, and by and by you’ll understand. This is no normal story. It’s a story that begins at the end and goes back to the beginning. Yes, like a school of salmon swimming upstream. I’m sure you’re like everyone else, you’ve read the tale as told by the man who wrote it. He writes so well that his words are like precious stones, jewels cut with the utmost precision. A man very strict about shades of meaning, your hero was; he practically required them to be mathematical. Endless calculations, based on gems and minerals. Have you seen the way he writes? He’s writing about a gunshot, and he makes it sound like poetry! His world is clean, clear, exact, honed by morning sunlight, enhanced with fragrances and horizons. The only shadow is cast by “the Arabs,” blurred, incongruous objects left over from “days gone by,” like ghosts, with no language except the sound of a flute. I tell myself he must have been fed up with wandering around in circles in a country that wanted nothing to do with him, whether dead or alive. The murder he committed seems like the act of a disappointed lover unable to possess the land he loves. How he must have suffered, poor man! To be the child of a place that never gave you birth . . .

I too have read his version of the facts. Like you and millions of others. And everyone got the picture, right from the start: He had a man’s name; my brother had the name of an incident. He could have called him “Two P.M.,” like that other writer who called his black man “Friday.” An hour of the day instead of a day of the week. Two in the afternoon, that’s good. Zujj in Algerian Arabic, two, the pair, him and me, the unlikeliest twins, somehow, for those who know the story of the story. A brief Arab, technically ephemeral, who lived for two hours and has died incessantly for seventy years, long after his funeral. It’s like my brother Zujj has been kept under glass. And even though he was a murder victim, he’s always given some vague designation, complete with reference to the two hands of a clock, over and over again, so that he replays his own death, killed by a bullet fired by a Frenchman who just didn’t know what to do with his day and with the rest of the world, which he carried on his back.

And again! Whenever I go over this story in my head, I get angry — at least, I do whenever I have the strength. So the Frenchman plays the dead man and goes on and on about how he lost his mother, and then about how he lost his body in the sun, and then about how he lost a girlfriend’s body, and then about how he went to church and discovered that his God had deserted the human body, and then about how he sat up with his mother’s corpse and his own, et cetera. Good God, how can you kill someone and then take even his own death away from him? My brother was the one who got shot, not him! It was Musa, not Meursault, see? There’s something I find stunning, and it’s that nobody — not even after Independence — nobody at all ever tried to find out what the victim’s name was, or where he lived, or what family he came from, or whether he had children. Nobody. Everyone was knocked out by the perfect prose, by language capable of giving air facets like diamonds, and everyone declared their empathy with the murderer’s solitude and offered him their most learned condolences. Who knows Musa’s name today? Who knows what river carried him to the sea, which he had to cross on foot, alone, without his people, without a magic staff? Who knows whether Musa had a gun, a philosophy, or a sunstroke?

Who was Musa? He was my brother. That’s what I’m getting at. I want to tell you the story Musa was never able to tell. When you opened the door of this bar, you opened a grave, my young friend. Do you happen to have the book in your schoolbag there? Good. Play the disciple and read me the first page or so . . .

So. Did you understand? No? I’ll explain it to you. After his mother dies, this man, this murderer, finds himself without a country and falls into idleness and absurdity. He’s a Robinson Crusoe who thinks he can change his destiny by killing his Friday but instead discovers he’s trapped on an island and starts banging on like a self-indulgent parrot. “Poor Meursault, where are you?” Shout out those words a few times and they’ll seem less ridiculous, I promise. And I’m asking that question for your sake. I know the book by heart, I can recite it to you like the Koran. That story — a corpse wrote it, not a writer. You can tell by the way he suffers from the sun and gets dazzled by colors and has no opinion on anything except the sun, the sea, and the surrounding rocks. From the very beginning, you can sense that he’s looking for my brother. And in fact, he seeks him out, not so much to meet him as to never have to. What hurts me every time I think about it is that he killed him by passing over him, not by shooting him. You know, his crime is majestically nonchalant. It made any subsequent attempt to present my brother as a shahid, a martyr, impossible. The martyr came too long after the murder. In the interval, my brother rotted in his grave and the book obtained its well-known success. And afterward, therefore, everybody bent over backward to prove there was no murder, just sunstroke.

Ha, ha! What are you drinking? In these parts, you get offered the best liquors after your death, not before. And that’s religion, my brother. Drink up — in a few years, after the end of the world, the only bar still open will be in Paradise.

I’m going to outline the story before I tell it to you. A man who knows how to write kills an Arab who, on the day he dies, doesn’t even have a name, as if he’d hung it on a nail somewhere before stepping onto the stage. Then the man begins to explain that his act was the fault of a God who doesn’t exist and that he did it because of what he’d just realized in the sun and because the sea salt obliged him to shut his eyes. All of a sudden, the murder is a deed committed with absolute impunity and wasn’t a crime anyway because there’s no law between noon and two o’clock, between him and Zujj, between Meursault and Musa. And for seventy years now, everyone has joined in to disappear the victim’s body quickly and turn the place where the murder was committed into an intangible museum. What does “Meursault” mean? Meurt seul, dies alone? Meurt sot, dies a fool? Never dies? My poor brother had no say in this story. And that’s where you go wrong, you and all your predecessors. The absurd is what my brother and I carry on our backs or in the bowels of our land, not what the other was or did. Please understand me, I’m not speaking in either sorrow or anger. I’m not even going to play the mourner. It’s just that . . . it’s just what? I don’t know. I think I’d just like justice to be done. That may seem ridiculous at my age . . . But I swear it’s true. I don’t mean the justice of the courts, I mean the justice that comes when the scales are balanced. And I’ve got another reason besides: I want to pass away without being pursued by a ghost. I think I can guess why people write true stories. Not to make themselves famous but to make themselves more invisible, and all the while clamoring for a piece of the world’s true core.

Drink up and look out the window — you’d think this country was an aquarium. Right, right, but it’s your fault too, my friend; your curiosity provokes me. I’ve been waiting for you for years, and if I can’t write my book, at least I can tell you the story, can’t I? A man who’s drinking is always dreaming about a man who’ll listen. That’s today’s bit of wisdom, write it down in your notebook. . .

It’s simple: The story we’re talking about should be rewritten, in the same language, but from right to left. That is, starting when the Arab’s body was still alive, going down the narrow streets that led to his demise, giving him a name, right up until the bullet hit him. So one reason for learning this language was to tell this story for my brother, the friend of the sun. Seems unlikely to you? You’re wrong. I had to find the response nobody wanted to give me when I needed it. You drink a language, you speak a language, and one day it owns you; and from then on, it falls into the habit of grasping things in your place, it takes over your mouth like a lover’s voracious kiss. I knew someone who learned to write in French because one day his illiterate father received a telegram no one could decipher. This was in the days when your hero was still alive and the colonists were still running the show. The telegram lay rotting in this fellow’s pocket for a week before somebody read it to him. In three lines, it informed him of his mother’s death, somewhere deep in the treeless country. He told me, “I learned to write for my father, and I learned to write so that such a thing could never happen again. I’ll never forget his anger with himself, and his eyes begging me to help him.” Basically, my reason’s the same as his. Well, go on, read some more, even if the whole thing’s written in my head. Every night, my brother Musa, alias Zujj, arises from the Realm of the Dead and pulls my beard and cries, “Oh my brother Harun, why did you let this happen? I’m not a sacrificial lamb, damn it, I’m your brother!” Go on, read!

Let’s be clear from the start: There were just two siblings, my brother and me. We didn’t have a sister, much less a slutty one, as your hero suggested in his book. Musa was my older brother, his head seemed to strike the clouds. He was quite tall, yes, and his body was thin and knotty from hunger and the strength anger gives. He had an angular face, big hands that protected me, and hard eyes because our ancestors lost their land. But when I think about it, I believe he already loved us then the way the dead do, with a look in his eyes that came from the hereafter and with no useless words. I don’t have many pictures of him in my head, but I want to describe them to you carefully. For example, the day he came home early from the neighborhood market, or maybe from the port, where he worked as a porter and handyman, toting, dragging, lifting, sweating. Anyway, that day he came across me while I was playing with an old tire, and he put me on his shoulders and told me to hold on to his ears, as if his head were a steering wheel. I remember how ecstatic I felt while he rolled the tire along and made a sound like a motor. His smell comes back to me too, a persistent mingling of rotten vegetables, sweat, muscles, and breath. Another picture in my memory is from the day of Eid one year. He’d given me a hiding the day before for some stupid thing I’d done and now we were both embarrassed. It was a day of forgiveness, he was supposed to kiss me, but I didn’t want him to lose face and lower himself by apologizing to me, not even in God’s name. I also remember his gift for immobility, the way he’d stand stock-still on the threshold of our house, facing the neighbors’ wall, holding a cigarette and the cup of black coffee our mother would bring him.

Our father had disappeared ages before, reduced to fragments by the rumors of people who claimed to have run into him in France, and only Musa could hear his voice. He’d give Musa commands in his dreams, and Musa would relay them to us. My brother had seen him again only once since he’d left, and from such a distance that he wasn’t really sure it was him anyway. As a child, I knew how to distinguish the days with rumors from the days without. When my brother Musa would hear people talk about my father, he’d come home, all feverish gestures and burning eyes, and then he and Mama would have long, whispered conversations that always ended in heated arguments. I was excluded from those, but I got the gist: For some obscure reason, my brother held a grudge against Mama, and she defended herself in a way that was even more obscure. Those were unsettling days and nights, filled with anger, and I recall my panic at the idea that Musa might leave us too. But he’d always return at dawn, drunk, oddly proud of his rebellion, seemingly endowed with renewed strength. Then my brother Musa would sober up and fade away. All he wanted to do was sleep, and so my mother would get him under her control again. I’ve got some pictures in my head, they’re all I can offer you. A cup of coffee, some cigarette butts, his espadrilles, Mama crying and then recovering very quickly to smile at a neighbor who’d come to borrow some tea or spices, moving from distress to courtesy so fast it made me doubt her sincerity, young as I was. Everything revolved around Musa, and Musa revolved around our father, whom I never knew and who left me nothing but our family name. Do you know what we were called in those days? Uled el-assas, the sons of the guardian. Of the watchman, to be more precise. My father worked as a night watchman in a factory where they made I don’t know what. One night, he disappeared. And that’s all. That’s the story I got. It happened in the 1930s, right after I was born. That’s why I always imagine him gloomy, wrapped up in a coat or a black djellaba, crouching in some dim corner, and silent, without so much as a single answer for me.

So Musa was a simple god, a god of few words. His thick beard and strong arms made him seem like a giant who could have wrung the neck of any soldier in any ancient pharaoh’s army. Which explains why, on the day when we learned of his death and the circumstances surrounding it, I didn’t feel sad or angry at first; instead I felt disappointed and offended, as if someone had insulted me. My brother Musa was capable of parting the sea, and yet he died in insignificance, like a common bit player, on a beach that today has disappeared, close to the waves that should have made him famous forever!

I almost never wept for him, I just stopped looking at the sky the way I used to. Moreover, in later years, I didn’t even fight in the War of Liberation. I knew it was won in advance, from the moment when a member of my family was killed because someone felt lethargic from too much sun. As soon as I learned to read and write, everything became clear to me: I had my mother, while Meursault had lost his. He killed, but I knew it was really a way of committing suicide. Now, it’s true that I reached those conclusions before the scenery got shifted and the roles reversed. Before I realized how alike we were, he and I, imprisoned in the same cell, shut up out of sight in a place where bodies were nothing but costumes.

And so the story of this murder doesn’t begin with the famous sentence “Maman died today” but with words no one has ever heard, spoken by my brother Musa to my mother on that last day, right before he went out: “I’ll be home earlier than usual.” It was a day, as I recall, without. Remember what I told you about my world and its binary calendar: the days with rumors about my father, and the days without, which Musa dedicated to smoking, arguing with Mama, and looking at me like a piece of furniture requiring nourishment. In reality, as I now realize, I did what Musa had done; he’d replaced my father, and I replaced my brother. But wait, I’m lying to you about that, just as for a long time I lied to myself. The truth is that Independence only pushed people on both sides to switch roles. We were the ghosts in this country when the settlers were exploiting it and bestowing on it their church bells and cypress trees and swans. And today? Well, it’s just the opposite! They come back sometimes, holding their descendants’ hands on trips organized for pieds-noirs or for people affected by their parents’ nostalgia, trying to find a street or a house or a tree with initials carved in its trunk. I recently saw a group of French tourists standing in front of a tobacco shop at the airport. Like discreet, mute specters, they watched us — us Arabs — in silence, as if we were nothing but stones or dead trees. Nevertheless, that’s all over now. That’s what their silence said.

I maintain that when you’re investigating a crime, you must keep in mind its essential elements: Who’s the dead man? Who was he? I want you to make a note of my brother’s name, because he was the one who was killed in the first place and the one who’s still being killed to this day. I insist on that, because otherwise, we may as well part right here. You carry off your book, I’ll take up the body, and to each his way. The genealogy I’m talking about is pretty pathetic in any case! I’m the son of the guardian, uld el-assas, and the Arab’s brother. Here in Oran, you know, people are obsessed with origins. Uled el-bled, the real children of the city, of the country. Everyone wants to be this city’s only son, the first, the last, the oldest. The bastard’s anxiety — sounds like there’s some of that rattling around, don’t you think? Everyone tries to prove he was the first — him, his father, or his grandfather — to live here. All the others are foreigners, landless peasants ennobled en masse by Independence. I’ve always wondered why people like that poke about so anxiously in cemeteries. Yes, yes they do. Maybe it’s from fear, or from the scramble for property. The first people to have lived here? Confirmed skeptics or recent newcomers call them “the rats.” This is a city with its legs spread open toward the sea. Take a look at the port when you walk down toward the old neighborhoods in Sidi El Houari, over on the Calère des Espagnols side. It’s like an old whore, nostalgic and chatty. Sometimes I go down to the lush garden on the Promenade de Létang to have a solitary drink and rub shoulders with delinquents. Yes, down there, where you see that strange, dense vegetation, ficuses, conifers, aloes, not to mention palms and other deeply rooted trees, growing up toward the sky as well as down under the earth. Below there’s a vast labyrinth of Spanish and Turkish galleries, which I’ve been able to visit, even though they’re usually closed. I saw an astonishing spectacle down there: the roots of centuries-old trees, seen from the inside, so to speak, gigantic, twisting things, like giant, naked, suspended flowers. Go and visit that garden. I love the place, but sometimes when I’m there I detect the scent of a woman’s sex, a giant, worn-out one. Which goes a little way toward confirming my obscene vision: This city faces the sea with its legs apart, its thighs spread, from the bay to the high ground where that luxurious, fragrant garden is. It was conceived — or should I say inseminated, ha, ha! —by a general, General Létang, in 1847. You absolutely must go and see it — then you’ll understand why people here are dying to have famo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter I

- Chapter II

- Chapter III

- Chapter IV

- Chapter V

- Chapter VI

- Chapter VII

- Chapter VIII

- Chapter IX

- Chapter X

- Chapter XI

- Chapter XII

- Chapter XIII

- Chapter XIV

- Chapter XV

- About the Author