- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

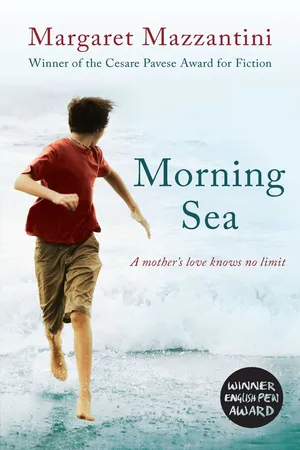

Morning Sea

About this book

From the multi-award-winning author of Twice Born comes this dazzling, emotionally charged tale of two mothers’ fight to protect their children’s futures

When the water is safer than the land...

As Gaddafi clings to power in Libya, Farid and his mother Jamila chance their luck on the hazardous crossing to Sicily. But as they hunker down in a trafficker’s battered old boat, the vastness of the Mediterranean begins to dawn. Meanwhile, in Sicily, Vito wanders the desolate beaches recalling his mother’s stories of her idyllic childhood in Libya. She has never forgotten – nor forgiven – the forces that tore her from her childhood love, a young Arab boy whose fate was very different from her own.

Moving back and forth between the continents, this deeply moving portrait focuses on two families and one stretch of water, and in terse, lyrical language, captures perfectly the dark, uncertain quality of our times.

When the water is safer than the land...

As Gaddafi clings to power in Libya, Farid and his mother Jamila chance their luck on the hazardous crossing to Sicily. But as they hunker down in a trafficker’s battered old boat, the vastness of the Mediterranean begins to dawn. Meanwhile, in Sicily, Vito wanders the desolate beaches recalling his mother’s stories of her idyllic childhood in Libya. She has never forgotten – nor forgiven – the forces that tore her from her childhood love, a young Arab boy whose fate was very different from her own.

Moving back and forth between the continents, this deeply moving portrait focuses on two families and one stretch of water, and in terse, lyrical language, captures perfectly the dark, uncertain quality of our times.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Morning Sea by Margaret Mazzantini, Ann Gagliardi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Colour of Silence

Vito scrambles over sea cliffs, descends into sandy coves. He’s left the village behind him, the noise of a radio, a woman hollering in dialect. Now it’s just wind and waves leaping high against the rocks, extending their paws like angry beasts, foaming, retreating. Vito likes the stormy sea. When he was a little boy, he’d jump in and let it slap him around. His mother, Angelina, back on the beach, would yell herself hoarse. She looked tiny as she stood there waving her arms like a marionette. She was such a little thing, with her dress flapping around her legs. The sea was stronger. Take a running start, ride the fast wave, slide as if on soap, be swallowed up by it, bang against the angry throat of the vortex. He’d roll, sand and big rocks tumbling him about on the murky bottom and leaving him dizzy. Sea in his nose, his belly, waves sucking him backwards, scaring him.

Real joy always contains some fear.

These were his best memories – his bathing suit full of sand, his eyes wounded and red, his hair like seaweed. Becoming a weightless rag, trembling with happiness and fear, lips blue, fingers numb. He’d come out for a little while, running, and throw himself down upon the warm sand, trembling and shivering like a mullet in its death throes. Then he’d dive back in, his brain devoid of thought, feeling more fish than human. So what if he didn’t make it back? That would be that. What was waiting for him back onshore, anyway? His angry mother, smoking. His grandmother’s octopus stew. His summer homework, nasty stuff, because there’s nothing worse than books and notebooks in the summer. And he always gets bad grades, an eternal debt of credits to make up.

One time when Angelina was trying to get him out of the water, she stepped on a sea urchin and lost her sunglasses. That time, she slapped him silly. Pulled him out of the water by his hair, banged him around like an octopus. That was the time he’d most hated her, the time he’d felt she loved him more than anything. That night, she let him sleep in her bed, in the crumpled white sheets, with her, her smell, her movements. His mother had separated from his father. At night, she’d stand in front of the door, beneath the palm tree, and smoke, an arm across her belly, the cigarette packet clutched in her hand. She’d talk to herself, moving her lips in silence. Her hair plastered to her forehead, making funny faces. She looked like a monkey ready to leap.

Now Vito is grown. They live outside Catania and come to the island only in the summer and sometimes at Easter. These are the last days of the holidays. His mother has to get back for the start of the school year. Vito has finished school. He’s done with the hassle of lies and copying off other kids, waking up at seven in the morning with bad breath. He passed the school-leaving exam. It took tutors, it took prodding, but he passed. He did a good job. The examiners liked him. He presented a history paper on the Tripolini, the Italians that Gaddafi banished from Tripoli in 1970. Vito’s research started with General Graziani, the butcher who led Mussolini’s troops in Libya, and ended with his own mother.

He talked about mal d’afrique, the nostalgia that turns sticky, like tar, and about the trip they took together, back in time. To Libya.

It was a total liberation. The next day, he took the biggest dump ever. He went out to celebrate in a club and kissed a girl. Too bad that afterwards she told him she’d made a mistake. Vito managed all the same to explore her mouth, and swelled up and trembled like when he was a kid in the waves.

Now Vito looks at the sea. He’s barefoot. He has prehensile feet, calloused like a sailor’s. It always happens at the end of the summer. His feet are ready to stay, to live bare on the cliffs and rocks.

It’s been a mindless summer, truly vacant. He slept late, swam infrequently. He’d go down to the sea in a daze. He read a few books in the cave as crabs climbed and retreated.

Today, he’s wearing a T-shirt and trousers. It’s windy.

Vito looks at the debris, pieces of boats and other remnants vomited up onto the beach that looks like a maritime rubbish dump.

There’s a war across the sea.

It’s been a tragic summer for the island. The same old tragedy, more this year.

Vito hasn’t gone into town very often. He’s seen the immigrant detention centre. It’s bursting at the seams and stinks like a zoo. He’s seen queues of the poor souls lined up outside the camp kitchen and the plastic toilet booths. He’s seen the fields at night, sown with silver blankets. He saw Tindara, their neighbour, scream and almost die of fright when a Tunisian slipped into her house to steal. He saw kids he knew when he was little, kids he doesn’t say hello to any more, making cauldrons of couscous for the Arab lunch of the wretches.

Vito doesn’t know what he wants to do with his life. He’d like to study art, something he thought of this summer and hasn’t told anyone yet. He draws well. It’s the only thing he’s always managed to do easily, naturally. Maybe because reason doesn’t come into it – all he has to do is follow his hand. Maybe because he spent so much time doodling in notebooks and on school desks instead of studying.

He looks at the remains of a boat, a flank with blue and green stripes, a star, and an Arab moon.

He hasn’t eaten a single slice of tuna this summer, not one sea bream. Just eggs and spaghetti. He doesn’t like to think about what the fish eat. He dreamt about it one night, the dark depths and a school of fish inside a human skull as if it were a cave full of fluttering sea anemones.

Until last summer he always went fishing. He’d tie a sack of mussels and scraps to a buoy. At sunrise, he’d find octopuses who had glued themselves to the bag and were trying to get inside it with their tentacles. If the octopuses were big, it would be a struggle. They’d suck onto him and he’d have to tear them off. At night, he’d go after squids with a fishing light. He’d use his fishing rod in the port, a spear in the caves. He loved wresting flesh from the sea.

This summer, there’s nothing that could make him go snorkelling. He’s spent his time on the hammock and only gone into town if he really had to. Too much sorrow. Too much chaos. But there’s still one part of the island that’s remained untouched by the world, just a few steps away from where the boats land and from the news crews.

Vito looks at the sea. One day, his mother said, You have to find a place inside you, around you. A place that’s right for you.

A place that resembles you, at least in part.

His mother resembles the sea, the same liquid glance, the same calm hiding a tempest inside.

She never goes down to the sea except sometimes at sunset, when the sun sliding past the horizon reddens the rocks to purple and the sky to blood, and seems truly like the last sun on earth.

Vito watched Angelina walk along the rocks, her hair unravelled by the wind, a spent cigarette in her hand. Scrambling along the cliff like a crab with the tide. It was just a passing moment, but he worried he’d never see her again.

His mother was Arab for eleven years.

She looks at the sea like the Arabs, as if she were looking at a blade, the blood already dripping.

Nonna Santa landed in Libya with the colonists in 1938. She was the seventh of nine children. Her father and her uncles made pottery. They set sail from Genoa beneath a pounding rain. The sky was filled with sodden handkerchiefs bidding farewell to the colonists of the Fourth Shore.

Nonno Antonio arrived on the last ship, the one that set sail from Sicily with sacks of seeds, vine shoots, bunches of chilli peppers. He was a thin little boy with olive skin. His hat was bigger than his face. He had never crossed the sea. He lived inland, at the foot of Mount Etna. His parents were farmers. They slept on their sacks. Antonio vomited out his soul. When they disembarked, he was deathly pale, but he perked up the second he got a whiff of the air. Mingled smells – coffee, mint, perfumed sweets. Not even the camels in the military parade stank. Vito must have heard Nonno Antonio’s story about landing in Tripoli thousands of times, about Italo Balbo in his hydroplane leading the way, about the immense tri-coloured flag spread out upon the beach and Mussolini astride his horse, the sword of Islam raised in his hand, pointing towards Italy.

His family spent a day seeing the sights of Tripoli and then they were taken to the rural villages. They found themselves face to face with kilometres of desert. Shrubs were the only vegetation. They set to work. Many of the Italians were Jewish.

They befriended the Arabs. They taught them agricultural techniques. They were poor people with other poor people. Their foreheads bore the same furrows of land and exertion. They cooked unleavened bread on hot stones, dry-cured their olives with salt. They dug wells, built walls to defend the cultivated land from the desert wind.

Santa and Antonio’s families ended up on neighbouring farms. They helped their parents with the farm work, saw the citrus groves grow up out of the sand, learnt Arabic. They exchanged their first kiss in Benghazi during a Berber horseshow in Il Duce’s honour.

Then war broke out. Friendly fire shot Italo Balbo down at Tobruk. A mistake, they said. English flares lit up the sky. The Italian c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for . . .

- About the Author

- Also Available

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Farid and the Gazelle

- The Colour of Silence

- Morning Sea