- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

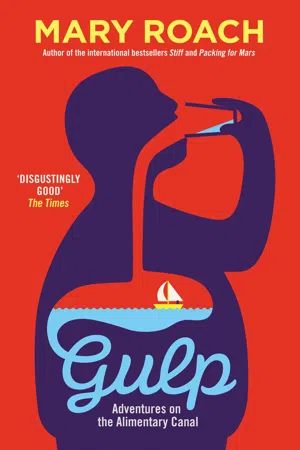

In her fantastically disgusting international bestseller, Mary Roach dives into the strange wet miracles of science that operate inside us after every meal

SHORTLISTED FOR THE ROYAL SOCIETY WINTON PRIZE 2014

‘Almost every page made me laugh out loud.’ The Sunday Times, Best Science Books of 2013

Eating is the most pleasurable, gross, necessary, unspeakable biological process we undertake. But very few of us realise what strange wet miracles of science operate inside us after every meal – let alone have pondered the results (of the research). How have physicists made crisps crispier? What do laundry detergent and saliva have in common? Was self-styled ‘nutritional economist’ Horace Fletcher right to persuade millions of people that chewing a bite of shallot seven hundred times would yield double the vitamins?

In her trademark, laugh-out-loud style, Mary Roach breaks bread with spit connoisseurs, beer and pet-food tasters, stomach slugs, potato crisp engineers, enema exorcists, rectum-examining prison guards, competitive hot dog eaters, Elvis' doctor, and many more as she investigates the beginning, and the end, of our food.

‘A wonderful nonfiction read… The journalism is gripping and the writing is intensely funny. If biology had been like this at school, my life would have taken a different path.’ Observer, Hidden Gems of 2016

SHORTLISTED FOR THE ROYAL SOCIETY WINTON PRIZE 2014

‘Almost every page made me laugh out loud.’ The Sunday Times, Best Science Books of 2013

Eating is the most pleasurable, gross, necessary, unspeakable biological process we undertake. But very few of us realise what strange wet miracles of science operate inside us after every meal – let alone have pondered the results (of the research). How have physicists made crisps crispier? What do laundry detergent and saliva have in common? Was self-styled ‘nutritional economist’ Horace Fletcher right to persuade millions of people that chewing a bite of shallot seven hundred times would yield double the vitamins?

In her trademark, laugh-out-loud style, Mary Roach breaks bread with spit connoisseurs, beer and pet-food tasters, stomach slugs, potato crisp engineers, enema exorcists, rectum-examining prison guards, competitive hot dog eaters, Elvis' doctor, and many more as she investigates the beginning, and the end, of our food.

‘A wonderful nonfiction read… The journalism is gripping and the writing is intensely funny. If biology had been like this at school, my life would have taken a different path.’ Observer, Hidden Gems of 2016

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gulp by Mary Roach in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Nose Job

TASTING HAS LITTLE TO DO WITH TASTE

THE SENSORY ANALYST rides a Harley. There are surely many things she enjoys about travelling by motorcycle, but the one Sue Langstaff mentions to me is the way the air, the great and odorous out-of-doors, is shoved into her nose. It’s a big, lasting passive sniff.4 This is why dogs stick their heads out the car window. It’s not for the feeling of the wind in their hair. When you have a nose like a dog has, or Sue Langstaff, you take in the sights by smell. Here is California’s Highway 29 between Napa and St. Helena, through Langstaff’s nose: cut grass, diesel from the Wine Train locomotive, sulphur being sprayed on grapes, garlic from Bottega Ristorante, rotting vegetation from low tide on the Napa River, toasting oak from the Demptos cooperage, hydrogen sulphide from the Calistoga mineral baths, grilling meat and onions from Gott’s drive-in, alcohol evaporating off the open fermenters at Whitehall Lane Winery, dirt from a vineyard tiller, smoking meats at Mustards Grill, manure, hay.

Tasting – in the sense of ‘wine-tasting’ and of what Sue Langstaff does when she evaluates a product – is mostly smelling. The exact verb would be flavouring, if that could be a verb in the same way tasting and smelling are. Flavour is a combination of taste (sensory input from the surface of the tongue) and smell, but mostly it’s the latter. Humans perceive five tastes – sweet, bitter, salty, sour, and umami (brothy) – and an almost infinite number of smells. Eighty to ninety percent of the sensory experience of eating is olfaction. Langstaff could throw away her tongue and still do a reasonable facsimile of her job.

Her job. It is a kind of sensory forensics. ‘People come to me and say, “My wine stinks. What happened?”’ Langstaff can read the stink. Off-flavours – or ‘defects’, in the professional’s parlance – are clues to what went wrong. An olive oil with a flavour of straw or hay suggests a problem with desiccated olives. A beer with a ‘hospital’ smell is an indication that the brewer may have used chlorinated water, even just to rinse the equipment. The wine flavours ‘leather’ and ‘horse sweat’ are tells for the spoilage yeast Brettanomyces.

The nose is a fleshly gas chromatograph. As you chew food or hold wine in the warmth of your mouth, aromatic gases are set free. As you exhale, these ‘volatiles’ waft up through the posterior nares – the internal nostrils5 at the back of the mouth – and connect with olfactory receptors in the upper reaches of the nasal cavity. (The technical name for this internal smelling is retronasal olfaction. The more familiar sniffing of aromas through the external nostrils is called orthonasal olfaction.) The information is passed on to the brain, which scans for a match. What sets a professional nose apart from an everyday nose is not so much its sensitivity to the many aromas in a food or drink, but the ability to tease them apart and identify them.

Like this: ‘Dried cherries. Molasses’ – treacle. Langstaff is sniffing a strong, dark ale called Noel. We are at Beer Revolution, an amply stocked, mildly skunky6 bar in Oakland, California, where I have an office (in the city, not the bar) and Langstaff has a parent in hospital. She could use a drink, and we have four. For demonstration purposes.

In general, Langstaff isn’t a talky person. Her sentences present in low, unhurried tones without italics or exclamation points. The question ‘Which beer do you want, Mary?’ went down at the end. When she puts her nose to a glass, though, something switches on. She sits straighter and her words come out faster, lit by interest and focus. ‘It smells like a campfire to me also. Smoky, like wood, charred wood. Like a cedar chest, like a cigar, tobacco, dark things, smoking jackets.’ She sips from the glass. ‘Now I’m getting the chocolate in the mouth. Caramel, cocoa nibs...’

I sniff the ale. I sip it, push it around my mouth, draw blanks. I can tell it’s intense and complex, but I don’t recognise any of the components of what I’m experiencing. Why can’t I do this? Why is it so hard to find words for flavours and smells? For one thing, smell, unlike our other senses, isn’t consciously processed. The input goes straight to the emotion and memory centres. Langstaff’s first impression of a scent or flavour may be a flash of colour, an image, a sense of warm or cool, rather than a word. Smoking jackets in a glass of Noel, Christmas trees in a hoppy, resinous India pale ale.

It’s this too: Humans are better equipped for sight than for smell. We process visual input ten times faster than olfactory. Visual and cognitive cues handily trump olfactory ones, a fact famously demonstrated in a 2001 collaboration between a sensory scientist and a team of oenologists (wine scientists) at the University of Bordeaux in Talence, France. Fifty-four oenology students were asked to use standard wine-flavour descriptors to describe a red wine and a white wine. In a second round of tasting, the same white wine was paired with a ‘red’, which was actually the same white wine yet again but secretly coloured red. (Tests were run to make sure the red colouring didn’t affect the flavour.) In describing the red-coloured white wine, the students dropped the white wine terms they’d used in the first round in favour of red wine descriptors. ‘Because of the visual information’, the authors wrote, ‘the tasters discounted the olfactory information’. They believed they were tasting red wine.

Verbal facility with smells and flavours doesn’t come naturally. As babies, we learn to talk by naming what we see. ‘Baby points to a lamp, mother says, “Yes, a lamp,”’ says Johan Lundström, a biological psychologist with the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia. ‘Baby smells an odour, mother says nothing.’ All our lives, we communicate through visuals. No one, with a possible exception made for Sue Langstaff, would say, ‘Go left at the smell of simmering hot dogs.’

‘In our society, it’s important to know colours’, Langstaff says over a rising happy-hour din. We need to know the difference between a green light and a red light. It’s not so important to know the difference between bitter and sour, skunky and yeasty, tarry and burnt. ‘Who cares. They’re both terrible. Ew. But if you’re a brewer, it’s extremely important.’ Brewers and vintners learn by exposure, gradually honing their focus and deepening their awareness. By sniffing and contrasting batches and ingredients, they learn to speak a language of flavour. ‘It’s like listening to an orchestra’, Langstaff says. At first you hear the entire sound, but with time and concentration you learn to break it down, to hear the bassoon, the oboe, the strings.7

As with music, some people seem born to it. Maybe they have more olfactory receptors or their brain is wired differently, maybe both. Langstaff liked to sniff her parents’ leather goods as a small child. ‘Purses, briefcases, shoes’, she says. ‘I was a weird kid.’ My wallet is on the table, and without thinking, I stick it under her nose. ‘Yeah, nice’, she says, though I don’t see her sniff. The performing-chimp aspect of the work gets tiresome.

While not discounting genetic differences, Langstaff believes sensory analysis is mainly a matter of practice. Amateurs and novices can learn via kits, such as Le Nez du Vin, made up of many tiny bottles of reference molecules: isolated samples of the chemicals that make up the natural flavours.

A quick word about chemicals and flavours. All flavours in nature are chemicals. That’s what food is. Organic, vine-ripened, processed and unprocessed, vegetable and animal, all of it chemicals. The characteristic aroma of fresh pineapple? Ethyl 3-(methyl-thio)propanoate, with a supporting cast of lactones, hydrocarbons, and aldehydes. The delicate essence of just-sliced cucumber? 2E,6Z-Nonadienal. The telltale perfume of the ripe Bartlett pear? Alkyl (2E,4Z)-2,4-decadienoates.

OF THE FOUR half-pints on the table between us, Langstaff prefers the lightest, a strawberry wheat beer. I like the IPA best, but to her that’s not a ‘sitting and sipping’ beer. It’s something she’d drink with food.

I ask Sue Langstaff – sensory consultant to the brewing industry for twenty-plus years, twice a judge at the Great American Beer Festival – what she’d order right now if she had to choose between an IPA and a Budweiser.

‘I’d get Bud.’

‘Sue, no.’

‘Yes!’ First exclamation point of the afternoon. ‘People pooh-pooh Bud. It’s an extremely well-made beer. It’s clean, it’s refreshing. If you’re mowing the lawn and you come in and you want something refreshing and thirst-quenching, you wouldn’t drink this.’ She indicates the IPA.

Of all the descriptors in the Beer Flavour Lexicon I brought with me today, Langstaff would apply just two to Bud: malty and worty. She warns me about equating complexity with quality. ‘All that stuff you read on wine bottles, in wine magazines, where they throw out a dozen descriptors? That’s not sensory evaluation. That’s marketing.’

Taste – as in personal preference, discernment – is subjective. It’s ephemeral, shaped by trends and fads. It’s one part mouth and nose, two parts ego. Even flavours that professional evaluators agree are ‘defects’ can come to signify superior taste. Langstaff mentions a small brewery in northern California that has been taking its beers right up to the doorstep of defective, adding strains of bacteria known for their spoilage effects. Whether through exposure or a desire to ride the cutting edge, people can acquire a taste for pretty much anything. If they can come to like the smelly-foot stink of Limburger cheese or the corpsey reek of durian fruit, they can come to enjoy bacteria-soured beer. (One assumes there are limits, however. Leaving olive oil in contact with rotting sediment at the bottom of a tank can create flavours enumerated on Langstaff’s Defects Wheel for Olive Oil as follows: ‘baby diapers, manure, vomit, bad salami, sewer dregs, pig farm waste pond’.)

Because it’s hard for people to gauge quality by flavour, they tend to gauge it by price. That’s a mistake. Langstaff has evaluated wine professionally for twenty years. In her opinion, the difference between a £250 bottle of wine and one that costs £15 is largely hype. ‘Wineries that sell their wines for $500 a bottle have the same problems as wineries that sell their wine for $10 a bottle. You can’t make the statement that if it’s low-cost it’s not well made.’ Most of the time, people don’t even prefer the expensive bottle – provided they can’t see the label. Paul Wagner, a top wine judge and founding contributor to the industry blog Through the Bunghole, plays a game with his wine-marketing classes at Napa Valley College. The students, most of whom have several years’ experience in the industry, are asked to rank six wines, their labels hidden by – a nice touch here – brown paper bags. All are wines Wagner himself enjoys. At least one is under £6 and two are over £30. ‘Over the past eighteen years, every time’, he told me, ‘the least expensive wine averages the highest ranking, and the most expensive two finish at the bottom’. In 2011, a Gallo cabernet scored the highest average rating, and a Chateau Gruaud Larose (which retails for about £40) took the bottom slot.

Unscrupulous vendors turn the situation to their advantage. In China, nouveau-riche status-seekers are spending small fortunes on counterfeit Bordeaux. A related scenario exists here vis-à-vis olive oil. ‘The United States is a dumping ground for bad olive oil’, Langstaff told me. It’s no secret among European manufacturers that Americans have no palate for olive oils. The Olive Center – a recent addition to the Robert Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science, on the campus of the University of California at Davis – aims to change that.

It starts with tastings. I don’t know which vineyard first ushered wine-tasting off the palates of vintners and into the mouths of everyday consumers, but it was a stroke of marketing genius. Wine-tastings spawn wine enthusiasts, wine collecting, wine tourism, wine magazines, wine competitions, (wine addictions) – all of it adding up to a massively profitable industry. Olive trees grow in the same climate and soil conditions as grapes. The olive oil people have been up in Napa Valley all along, going, ‘Hey, how do we get a piece of this action?’

In addition to hosting tastings, the Olive Center has hired Langstaff to train a new UC Davis Olive Oil Taste Panel. Taste panels (or flavour panels, as they are more accurately called) have typically been made up of industry professionals. Langstaff wants to open it up to novices, for the simple reason that know-nothings are easier to train than know-it-alls. The centre has a call for apprentice tasters on its website. The ‘try-outs’ are coming up. At least one know-nothing will be there.

THE OLIVE CENTER is smaller than its name suggests. It consists of a single office and a shared receptionist on the ground floor of the Sensory Building at the Robert Mondavi Institute. Bottles of oil and canned olives line the tops of cabinets and have begun to colonise the wall-to-wall. There’s no room in the centre to hold the try-outs, so they are taking place next door in the Silverado Vineyards Sensory Theater, the building’s lecture hall and classroom tasting facility. (Silverado helped fund it. Additionally, each seat has a sponsor, with the name engraved on a small plaque.)

Langstaff makes her entrance burdened like a pack mule. Three tote bags hang off her shoulders, and she wheels a multi-tiered cart crammed with oils, laptops, water bottles, and stacks of cups. She wears dun-coloured trousers, black sport sandals, and a short-sleeved shirt in the Hawaiian style, though without an island motif. She calls roll: twenty names. Of them, twelve will make the first cut, and six will go on to apprentice.

Langstaff lays out the ground rules for future apprentices: be here, be on time. Be agreeable. ‘We will be evaluating some nasty oils. You will have to put them in your mouth.8 For the good of science. For the good of olive oil. We are here to help the producers, to tell them, What attributes does the oil have, does it have defects, what can they do differently next year – treat the olives better, pick them at a different time, et cetera.’ There will be no pay. No one will reimburse for the seven-dollar parking fee. The existing panellists are known to have some prickle, to borrow an official olive-oil sensory descriptor.

‘You may be thinking, wow, I really don’t want to be on this thing.’ The faint of heart are invited to pack up and go. No one moves.

‘All right then.’ Langstaff surveys the room. ‘Shields up.’ She is referring to removable panels used to partition the room’s long tables into private tasting booths. This way, you aren’t influenced by the facial expressions (or test answers) of the people seated next to you. Hired sensory-science students move along the rows, pulling the panels out of slots in the front of the tables and sliding them into place, like helpers on a game-show set.

A plastic tray is set in front of each of us. The trays hold eight small lidded cups: our first test. Each cup holds an aromatic liquid. Swirl, sniff, identify. A few seem easy: almond extract, vinegar, olive oil. Apricot required two full minutes of deep thought. Others remain unfamiliar no matter how many times and how deeply I sniff. According to the journal Chemical Senses, a ‘typical human sniff’ has a duration of 1.6 seconds and a volume of about half a litre. I’m sniffing twice as hard. I’m sniffing the way clueless Americans try to make non-English speakers understand them by shouting. One aroma will turn out to be olive brine – the water from a bottle or can of olives. Reflecting the preponderance of olive people trying out today, an impressive thirteen out of twenty get this right.

Next is a ‘triangle test’: three olive-oil samples, two of them identical. Our task is to identify the odd one out. We are given paper cups of water for rinsing and, for spitting, large red plastic cups of the kind that litter the lawns and porches of American fraternity houses on weekend mornings. The red here today perhaps serving as a warning: Do not drink! Langstaff sits at the front of the room, reading a newspaper.

It’s not going well here in the B.R. Cohn Winery seat. All three oils taste the same to me: a hint of freshly mown grass, with a peppery finish. I do not detect apple, avocado, melon, pawpaw, old fruit bowl, almond, green tomato, artichoke, cinnamon, cat urine, hemp, Parmesan cheese, fetid milk, plaster bandages, crushed ants, or any other olive-oil flavour, good or bad, that might set one of these oils apart. With time running out, I don’t bother spitting. I’m sipping oil as though it’s tea. Langstaff glances at me over her glasses. I wipe my lips and chin with my palm, and a shiny smear comes away.

Our final challenge is a ranking test: five olive oils of differing degrees of bitterness. This proves a challenge for me, as I would not have described any o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 • Nose Job: Tasting has little to do with taste

- 2 • I’ll Have the Putrescine: Your pet is not like you

- 3 • Liver and Opinions: Why we eat what we eat and despise the rest

- 4 • The Longest Meal: Can thorough chewing lower the national debt?

- 5 • Hard to Stomach: The acid relationship of William Beaumont and Alexis St Martin

- 6 • Spit Gets a Polish: Someone ought to bottle the stuff

- 7 • A Bolus of Cherries: Life at the oral processing lab

- 8 • Big Gulp: How to survive being swallowed alive

- 9 • Dinner’s Revenge: Can the eaten eat back?

- 10 • Stuffed: The science of eating yourself to death

- 11 • Up Theirs: The alimentary canal as criminal accomplice

- 12 • Inflammable You: Fun with hydrogen and methane

- 13 • Dead Man’s Bloat: And other diverting tales from the history of flatulence research

- 14 • Smelling a Rat: Does noxious flatus do more than clear a room?

- 15 • Eating Backwards: Is the digestive tract a two-way street?

- 16 • I’m All Stopped Up: Elvis Presley’s megacolon, and other ruminations on death by constipation

- 17 • The Ick Factor: We can cure you, but there’s just one thing

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Illustration Credits

- About the Author