eBook - ePub

Contested Modernity

Sectarianism, Nationalism, and Colonialism in Bahrain

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Discussions of the Arab world, particularly the Gulf States, increasingly focus on sectarianism and autocratic rule. These features are often attributed to the dominance of monarchs, Islamists, oil, and ‘ancient hatreds’. To understand their rise, however, one has to turn to a largely forgotten but decisive episode with far-reaching repercussions – Bahrain under British colonial rule in the early twentieth century.

Drawing on a wealth of previously unexamined Arabic literature as well as British archives, Omar AlShehabi details how sectarianism emerged as a modern phenomenon in Bahrain. He shows how absolutist rule was born in the Gulf, under the tutelage of the British Raj, to counter nationalist and anti-colonial movements tied to the al-Nahda renaissance in the wider Arab world. A groundbreaking work, Contested Modernity challenges us to reconsider not only how we see the Gulf but the Middle East as a whole.

Drawing on a wealth of previously unexamined Arabic literature as well as British archives, Omar AlShehabi details how sectarianism emerged as a modern phenomenon in Bahrain. He shows how absolutist rule was born in the Gulf, under the tutelage of the British Raj, to counter nationalist and anti-colonial movements tied to the al-Nahda renaissance in the wider Arab world. A groundbreaking work, Contested Modernity challenges us to reconsider not only how we see the Gulf but the Middle East as a whole.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Ethnosectarian Gaze and Divided rule

Lorimer’s Gazetteer included Bahrain’s first systematized attempt at a population census that his team conducted in the early 1900s. It is useful to begin by quoting the relevant passages in full:

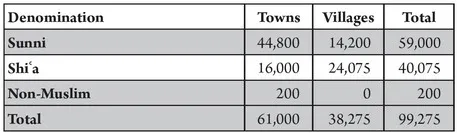

The principality then contains . . . 4 towns with a population of 60,800 souls and 104 villages with a population of 38,275; in all 99,075. To these must be added about 200 non-Mohammadans at Manamah, making a grand total of 99,275 settled inhabitants. Of the whole population of about 100,000 souls some 60,000, chiefly townsmen, are Sunnis and about 40,000, mostly villagers, are Shi’ahs.

The largest community – for it cannot be called a tribe – in the principality is undoubtedly that of the . . . Baharinah, who compose nearly the whole of the Shi’ah community . . . The remainder of the people, except a few foreigners such as Persians and Basrah Arabs, Hindus, Jews, etc., belong to various Sunni tribes or classes.1

Hence, in terms of ‘primordial cleavages’, Lorimer would apply the following divisions to the local population: at the ‘community’ level were the two great sects of Islam, Sunni (sixty percent) and Shiʿa (forty percent). Sunnis were divided into Huwala and ‘Tribes’, while the local Shiʿas were composed of Baharna. Added to those would be small groups of various ‘foreigners’ existing on the island.

Table 1: Sect-composition of the population of Bahrain in the early twentieth century according to Lorimer

Source: QDL, ‘Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol. II. Geographical and Statistical. J G Lorimer. 1908’ [238] (265/2084), IOR/L/PS/20/C91/4, http://www.qdl.qa/en/archive/81055/vdc_100023515712.0x000042.

Lorimer’s categorizations were based on his readings of existing social identifiers at the local level. In Bahrain’s setting, where the overwhelming majority of the population was Muslim and Arabic speaking, sect was the most obvious social cleavage, as even without the modern tools of censuses, one could immediately recognize that there was a sizable presence of both sects. Furthermore, at first sight, it seemed a relatively clear demarcation, with each individual being either Sunni or Shiʿa (with a few cases of mixed marriages and conversions). As we will see, however, even this simple binary was in reality not so clear-cut, as there existed several madhhabs, or schools of jurisprudence, which complicated the rigid picture of only two distinct sect groupings.

Ethnic constructions are by nature more porous, vague, and less stable social categories.2 To begin, it becomes necessary to give an overview of the different social group identifiers found within Bahrain’s social landscape. Let us start with the Huwala.3 Nowadays, the collective social consciousness uniting those who self-identify as Huwala could roughly be described as Sunnis with extensive historical, social, and familial ties across both sides of the Gulf, but who see their aspirations and identity anchored in Arab culture, thus considering themselves Arabs. This perception, of course, has been contested by different parties, as well as being porous and open to reshaping as a social construct. They would be termed at different times and by different actors as Arabs, Persians, Arabized Persians, or Persianized Arabs. Furthermore, as will emerge during this study, there would be contestation on the coverage and elasticity of Huwala as a social category, with the term sometimes used to exclude and at others to include individuals who would be classified as, for example, Khunjis or ʿAwadhis.

Similarly, the collective consciousness that unites those who today would self-identify as Baharna could roughly be summarized as Shiʿa Arabs whose roots lie in the agricultural and fishing villages of the islands of Bahrain.4 Just like the case of ‘Huwala’, the term ‘Baharna’ would also be malleable and porous across time, facing contestation from different actors, albeit in different ways.5 As will be shown, the term would sometimes be used to exclude and at others to include people identified as ‘Hasawis’, ‘Qatifis’, those with links to areas in Iraq (e.g. Helli or Basrawi), or those with links to parts of modern-day Iran (e.g. Muhammara).

Finally, ‘tribal origins’ is a social category whose members today would self-identify as individuals who belong to one of the tribes of the Arabian Peninsula. Tribes, of course, are a particular socio-economic formation in the Arab world that have been extensively written about, with the great Arab sociologist Ibn Khaldun describing them as the epitome of strong ʿAsabiyyah, or social solidarity based on shared kinship and group consciousness.6 The most influential tribes in Bahrain are those of the ʿUtub, with the ruling family of al-Khalifa at the top of the pack.7 However, in the context of Bahrain, being of ‘tribal origin’, regardless of the particular tribe, increasingly also takes on the form of a social marker that is used to identify a particular individual’s background, similar to how ‘Huwala’ or ‘Baharna’ function.

While they shared a common religion and language, Lorimer treated each of the above social identifiers as different and clearly defined ethnic communities or ‘classes’ that made up the ‘local’ population. This was complemented by demarcating smaller groups of ‘foreigners’. He identified the vast majority of foreigners as ‘Persians’, mainly Shiʿa but also including some Sunnis, most of whom today self-identify as ‘ʿAjams’, and who no longer would identify as ‘foreigners’ but as locals of Bahrain.8 Being labelled as a ‘foreigner’, however, had strong legal, political, and social consequences in the times of Lorimer, as will become apparent in the following narration.9

THE ETHNOSECTARIAN GAZE

These ethnosectarian markers and identifiers, always malleable and shiftable as social constructs, obviously existed in Bahrain prior to the arrival of Lorimer, who used them as the basis for demarcation in his census. The demarcations as used by him, however, constituted a new form of knowledge and social categorization. This was in line with colonial practice elsewhere.10 In the words of one scholar, it was:

[M]ade manifest in the activities of investigation, examination, inspection, peeping, poring over, which were accompaniments to the colonial penetration of a country. In ethnographic description and scientific study, in the curious scrutiny of the colonized by the colonizer, there was much of the attitude of the voyeur as well as of the map-maker. In writing, the gaze appears as bird’s-eye description, and is embodied in the high vantage point or knowledgeable position taken up by a writer or traveller as he re-creates a scene.11

What most defined this colonial gaze in Bahrain was its ethnosectarian lens, which was a systemic approach that saw ethno-sect cleavages as the underlying epistemic fault lines that shaped local society and its political power, practices, and discourse. Thus, the ethnosectarian gaze was a way of viewing and categorizing the social world, in which communities were primarily defined and composed of different sects and ethnicities. The local population, its actions, laws, and social make-up were to be analysed mainly based on ethno-sect divisions. The British focus on such demarcations emphasized differences in ethno-sects that they presented as contrasting and clear-cut (Sunni vs. Shiʿa and Baharna vs Huwala vs. Tribes), rather than highlighting ethnic and religious commonalities (e.g. Muslim and Arab). Censuses, institutions, laws, forms of mobilization, and other apparatuses of power were to be organized mainly around these ethno-sect fault lines, which are elevated to become the most important markers on the political level.

Other socio-economic-political factors, such as kinship, class, geography, trade, and production relations take a back seat to these different ‘primordial’ elements. This does not mean that these other factors played no role. The British in fact displayed a knack for documenting different aspects of economy, society, and governance in excruciating detail. However, the basic building blocks that composed local society and its politics, from the British point of view, were to be distinct sects and ethnicities.

Just like other forms of orientalism, this ethnosectarian gaze, although originally based on the colonial reading of the local situation on the ground, would increasingly morph and take on a life of its own, similar to an artist’s impression of real-life figures projected onto a painting, where the two increasingly resemble one another only tangentially. Unlike the painting, however, such ethnosectarian outlooks would interact and feed back into local events, generating real effects on the ground.

To illustrate this point further, let us return to Lorimer’s section on Bahrain, in which he would continue:

Although the Baharna are numerically the strongest class, they are far from being politically the most important; indeed, their position is little better than one of serfdom. Most of the date cultivation and agriculture of the islands is in their hands; but they also depend, though to a less extent than their Sunni brethren, upon pearl diving and other seafaring occupations.

The Huwala are the most numerous community of Sunnis; but they are all townsmen living by trade and without solidarity among themselves. Consequently, they are unimportant except commercially. The ʿUtub, the Sadah and the Dawasir are the most influential tribes in Bahrain.12

These passages are revealing, for...

Table of contents

- Cover

- More Praise for Contested Modernity

- RADICAL HISTORIES OF THE MIDDLE EAST

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Approaching Absolutism, Nationalism, and Sectarianism in the Gulf

- 1 The Ethnosectarian Gaze and Divided Rule

- 2 Politics and Society Before Divided Rule, 1783–1900

- 3 Al-Nahda in Bahrain, 1875–1920

- 4 Contesting Divided Rule, 1900–1920

- 5 ‘Fitnah’: Ethnosectarianism Meets al-Nahda, 1921–1923

- Postscript: the rise of absolutism and nationalism, 1923–1979

- Conclusion: state and society between sectarianism and nationalism

- Bibliography

- Imprint Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Contested Modernity by Omar H. AlShehabi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.