Twelve

It Must Mean …

Something

In Brief

‘Descartes and the Gut: “I’m Pink Therefore I Am”’

by D. G. Thompson (published in Gut, 2001)

Some of what’s in this chapter: Foul words for referees. • The decline of public insult in London • How beats the poet’s heart, electrically • The the the the the the the the the the the, in order • The scholar’s colon • Bad highlighting • Dude • Bob, by the look of him • Gówsü; Déznep; Wítaw; Thôbonf; Mávquawpûnt; Stisk • ’Meaning’ meaning ‘meaning’

The Curse of the Referee

Do swear words have predictable effects on football referees? A team of Austrian scientists tackles that question in a study called ‘May I Curse a Referee? Swear Words and Consequences’. Stefan Stieger, of the University of Vienna, together with Andrea Praschinger and Christine Pomikal, who describe themselves as ‘independent scientists’, published their report in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine.

Football referees enforce the laws of the game set forth by the sport’s governing organization, FIFA (the Fédération International de Football Association). The pertinent regulation is FIFA’s Law 12 (‘Fouls and Misconduct’), whose very last section – Section 81 – simply says: ‘A player who is guilty of using offensive, insulting or abusive language or gestures must be sent off.’

Stieger, Praschinger, and Pomikal performed their research in two steps. First, they obtained some swear words. Then, obscenities in hand, they found some referees who were willing to answer a survey.

The team began by drawing up a list of one hundred potential swear words. They pared the list by recruiting thirteen German-speaking residents of Austria, six women and seven men. Each Deutsch-Lautsprecher evaluated each word, rating both its degree of insultingness and whether it could be properly applied to both men and women. ‘Participants [also] had to rate the insulting content of each swear word. Does the swear word concern the person’s power of judgment (e.g., blind person), intelligence (e.g., fool), appearance (e.g., fatso), sexual orientation (e.g., bugger), or genitals (e.g., crap)?’

The researchers then found 113 game game referees from across Austria, and posed the following situation to each of them: during a stoppage in play, one team’s captain comes up to you and suggests you make a particular ruling. You decline. ‘Hereupon the team captain says … (the swear word mentioned below), turns around and walks [away].’ Do you, the referee, respond by issuing (1) a red card or (2) a yellow card or (3) an admonition, or do you (4) do nothing at all? The referee was asked this for each of the twenty-eight swear words.

Their answers showed a clear pattern. ‘Analyzing all swear words independent of their offensive nature, it was found that 55.7% of the swear words would have received a red card, although Law 12 would have prescribed a red card in all cases.’ Only a very few officials would always, automatically, eject the player.

Digging into the nitty-gritty of the data, the researchers gained two general insights. First, ‘that the decision to assign any card was dependent on the insulting content of the swear word’. Second, that ‘referees would have issued a red card for sexually inclined words or phrases rather than for terms insulting one’s appearance’.

Praschinger, Andrea, Christine Pomikal, and Stefan Stieger (2011). ‘May I Curse a Referee? Swear Words and Consequences.’ Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 10: 341–45.

May We Recommend

‘Swearing as a Response to Pain’

by Richard Stephens, John Atkins, and Andrew Kingston (published in Neuroreport, 2009, and honoured with the 2010 Ig Nobel Prize in peace)

Injury to Insult

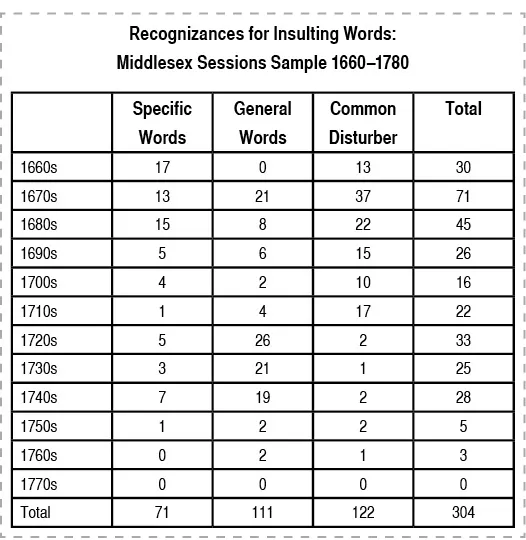

Insults just aren’t what they used to be, according to a study called ‘The Decline of Public Insult in London 1660–1800’. The study’s author, Robert B. Shoemaker, teaches eighteenth-century British history at Sheffield University, in the UK.

Professor Shoemaker pored through records of court proceedings from the late sixteenth through the early nineteenth centuries, paying special attention to the insults. Time was, insulting someone in public – or even in private – could easily propel you into court, and thence, if the insult was good or your luck wasn’t, to jail.

Shoemaker charted the number of insult-fuelled prosecutions in the consistory court of London over those centuries. ‘The pattern is clear’, he writes, ‘a massive increase in the late sixteenth century to a peak in the 1620s and 1630s, followed by a collapse ... By the late eighteenth century per capita prosecutions in London had fallen to only one or two per 100,000 per year.’ By the late 1820s, the number of prosecutions had dropped to an insulting one or two, total, per year.

(The high point for legal action, by the way, was 1633, the year Samuel Pepys was born. One can only speculate at how much more colourful his famous diary might have been had Pepys lived a generation earlier, during London’s golden age of insult.)

As the years rolled by, individual nasty words lost some of their power to trigger prosecution. Legal proceedings dealt, instead, with more general allegations. Court documents became less fun to read, with fewer bold, juicy epithets, the accusations now built of mushy phrases such as ‘opprobrious names’, ‘scandalous abuse’, or ‘grossly insulting’.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries revolutionized the legal handling of insult, Shoemaker suggests in telling us that ‘the very nature, function and significance of the insult was changing over this period’.

He invokes the words of King’s College London historian Laura Gowing. Gowing emphasized that in earlier years, ‘Defamations rarely happened inside private houses, at meals, or within private conversation, but were staged, often in the open, with an audience provided by the witnesses who, “hearing a great noise” in the street, left their work or houses to investigate or intervene ... the doorstep was a crucial vantage point for the exchange of insult.’

But by the eighteenth century, Shoemaker reports, ‘the insult became less public’. Insults moved indoors. Many ‘took place in semi-private locations, such as yards, shops, pubs and houses, where there were not always many witnesses’. Also, ‘there was much less certainty about whether defamatory words automatically destroyed reputations’, and so, ‘correspondingly, the power of insulting words was declining’.

All this tells us something sad about modernization: ‘At a basic level, due to frequent geographical mobility eighteenth-century Londoners did not know or take an interest in the activities of their neighbours as much as they used to.’

In this view of things, public insults declined because modern citizens no longer loved their neighbours.

Shoemaker, Robert B. (2000). ‘The Decline of Public Insult in London 1660–1800.’ Past and Present 169 (1): 97–131.

Measures of Poetry

Poetry is said, by poets, to make the heart flutter and the breath catch. A team of German, Swiss, and Austrian scientists showed that the claim is quite true, at least under certain laboratory conditions.

The researchers tried to describe this lyrically. They sought, they say, ‘to investigate the synchronization between low frequency breathing patterns and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) of heart rate during guided recitation of poetry’.

Twenty healthy individuals volunteered to spend twenty minutes reading aloud hexameter verse from ancient Greek literature. These volunteers were German speakers. They read a passage from a German translation of Homer’s heart-pounding, breath-forcing epic The Odyssey...