- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

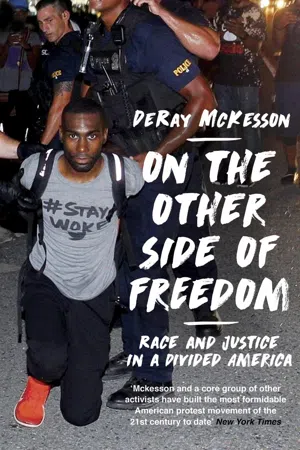

Five years ago, DeRay Mckesson quit his job as a schoolteacher, moved to Ferguson, Missouri, and spent the next 400 days on the streets as an activist, helping to bring the Black Lives Matter movement into being.

Now, in his first book, he draws on his own experiences – of growing up without his mother, with a father in recovery, of having a house burn down and a bully chase him home from school, of pacifying a traffic cop at gunpoint and being dragged out of a police station by his ankles, of determined activism on the streets and in the White House – to make the case for hope, for believing a better future is possible. It is a visionary’s call to take responsibility for imagining, and then building, the world we want to live in.

Now, in his first book, he draws on his own experiences – of growing up without his mother, with a father in recovery, of having a house burn down and a bully chase him home from school, of pacifying a traffic cop at gunpoint and being dragged out of a police station by his ankles, of determined activism on the streets and in the White House – to make the case for hope, for believing a better future is possible. It is a visionary’s call to take responsibility for imagining, and then building, the world we want to live in.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access On the Other Side of Freedom by DeRay Mckesson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politik & Internationale Beziehungen & Sozialwissenschaftliche Biographien. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THREE

The Problem of the Police

You don’t make progress by standing on the sidelines, whimpering and complaining. You make progress by implementing ideas.

—SHIRLEY CHISHOLM

I could feel the mixture of misplaced fear and power in his voice, on his face, in the tension in his arm as he steadied his gun, pointing it at my face and then torso, yelling and cursing. I just remember fragments of his rage as he barked, “Put your fucking hands on the steering wheel,” and when I complied, he continued, “What the fuck were you doing?” He was young—likely my age, or slightly older, both of us just having entered adulthood, wearing it now like an ill-fitting jacket. The sun hadn’t yet broken through the sky, and dew was still on my windshield. I lived around the corner and hadn’t made it far before his flashing lights appeared.

“It’ll be okay,” I said to him in a low, level tone, repeatedly, as he approached the driver’s-side window where I sat. Sometimes fear is a luxury, the by-product of having the time and space to process, to consider options and alternatives. On that day, though, the fear came later. As the events unfolded, I felt like I was the sixth-grade math teacher that I used to be, trying to talk one of my students down from a tantrum, using a calm, steady tone to mask my emotion. I knew that I couldn’t yell back, that an escalation would certainly end in disaster, that I couldn’t exit the car, and that no phone call would be possible while his gun was pointed at me. And I sensed that silence wouldn’t work in my favor either. The officer yelled and cursed as he approached my window for reasons I don’t think either of us knew, and as he carried on, the only words that found their way to my lips were, “It’ll be okay,” over and over. It was all that I could think of to make the situation less tense—to calm his frenzy. I think it just wasn’t my time to leave this earth, because it worked. He lowered the gun, he gave me neither a ticket nor a warning, he simply got back in his car and drove away.

Later, I called a former mentor and friend who worked in the Baltimore City State’s Attorney’s Office and told her what happened. I asked her how to report it, and she told me to let it go and to be more careful next time. I did as she said. That was in 2009.

Conflict exists in community. And not all conflict is the same; it has dimensions, nuance. If we are to live in community with each other, we must acknowledge this reality. Living in community requires a shared set of values and norms to serve as guideposts, defining the behaviors that we want to encourage and discourage, outlining the actions that make our community stronger and those that take away from its strength. In effect, we have rules for dealing with conflict. It is in this context that we understand that the choice to live among others requires the presence of a mechanism for responding to conflict, to instances when norms and values are broken or alleged to have been broken. But the choice to live in community also means that the community must dictate those norms and values for itself and must be able to manage the set of interventions used when conflict inevitably arises.

In ways large and small, we cede aspects of individual autonomy when we choose to live with one another. From the stop signs and traffic lights that create order on our roads, to trusting the FDA to ensure that the foods we eat are safe, we acknowledge that there are some things that individuals should not be able to decide on their own, as the impact on the larger community is too great.

CHIEF IN OUR DESIRE for a well-functioning community is, among other things, the desire that order be preserved, that conflicts be managed in ways that both make us safe and make us feel safe. No one wants disorder or chaos—not in their home, not in their neighborhood, not in their life. Sometimes, though, the compromises we make to purportedly keep order imperil us in unexpected ways. This is true of the way that our desire for safety has manifested. In a cruel twist, it has led us to make sacrifices that make us less safe, that increase the conflicts in our communities, and that empower a set of citizens to create conflict with impunity.

And it is our desire for safety, combined with measures for conflict management that prize the whims of the most privileged among us, that have led us to the state of policing in this country today.

The police in America have positioned themselves to be the first defense in addressing conflict. And that evolution has coincided with the fact that conflict is treated uniformly for people of color and other marginalized groups, while conflict is treated with nuance for white people. In theory, the police are the neutral party that responds to conflicts. But power, especially unchecked power, is never neutral. We know that the police function altogether differently depending on who you are or where you come from. The theory of policing is quite far from the reality of policing. For us, at least, that is.

They primarily wield negative power—that is, they take away to purportedly give. They seize, detain, arrest, imprison, and kill to maintain law and order in society, in order to manage conflict. What does it mean that the institution we’ve created to respond to conflict primarily uses means that are expressly for destruction and not for building? They do nothing to equip people with tools and resources to make better choices in the future, to learn how to manage conflict in the absence of intervention, to understand how their decisions impact the larger society.

Some people would argue that this is not their role. And given the way they have been allowed to function to date, these people are right. From movies to TV shows, to stump speeches and rallies, they have come to convince society that the only way to ensure safety is to employ negative power with both discretion and impunity. But we know that this does not increase the reality of safety, even if it increases the perception of safety. In many ways, the police are the gateway into the larger system of incarceration. They are not arbiters, they are ushers, shepherding men and women, and increasingly children, into subjection.

It is the people on the margins who are most aware of the dissonance between the theory and practice of the police and policing. There are three reasons for this: first, because they have intimate knowledge of the difference between conflicts of survival and conflicts of choice, and of how the police respond to both; second, because they have endured the presence of negative power as a means of control in the name of order, stability, and community for ages; and last, because they know that their instances of conflict in community almost always involve the weight of the police, whereas those of other members of the community, namely those who are white, do not.

Conflicts of survival arise as a result of the conditions created by the inequity in society, conditions like poverty and its concentration, mass incarceration, mass supervision, or the structural lack of access. This is not to excuse any range of conflicts that arise as a result of personal failures in judgment, but to note that some are a result of choices that have been made or allowed at the structural level. So there are high amounts of reported theft in places where poverty is the most stark, high levels of drug use and distribution in places where poverty and incarceration coincide, gun crimes in communities of densely concentrated poverty, and assaults in places where the traditional justice system has failed and a system of street justice is all anyone knows.

Conflicts of choice are those that are primarily the result of the personal decisions of an individual and not the result of systemic failures resulting in inequity. These are things like tax fraud, domestic abuse, insider trading, arson, embezzlement.

As a society, we have control over the conditions that lead to the conflicts of survival. And as a society, we have largely made the choice that we will allow them to continue. We could choose to end poverty; end homelessness; develop a robust program for addressing mental illness; guarantee that every adult and child has food and shelter; and institute a living wage and work opportunities for everyone. We could make these choices at a much larger scale in society. But we choose not to.

The consolidation of negative power, especially with no oversight or accountability, is the gateway to totalitarianism. Communities of color and marginalized communities have experienced the realities of how the heavy presence of negative power can fundamentally alter life forever. We’re increasingly seeing unrest that either begins with police violence or is sustained because of the absence of the police. It is important to remember that this negative power is not used in white communities with as much frequency or with the same intensity that it is used in communities of color. And this matters, because white people experience a host of diversion programs and their like when they engage in similar types of conflict. We also see the police create a conflict in order to then solve the conflict—the escalation of conflicts involving actors with mental illness is a ready example of this.

Will we always need a response to conflict? Yes. Do we need the police as they currently exist? No. It is not simply that policing is broken. This isn’t like a toy. Policing isn’t something to be bandaged up and fixed. The institution of policing is built on an overly simplistic understanding of conflict, flawed assumptions about reducing conflict over time, and a denial of the way that structural bias influences the way conflict is addressed. Policing as we know it is the wrong response to the challenges of conflict that we experience in communities. I think of policing today as a drinking glass with holes in it. No matter how many times you plug a hole here, mend one there, water continues to leak. At some point, you need to acknowledge the glass is faulty. That’s policing.

Importantly, the problem is not limited to a few bad apples, but rather a bad barrel—today’s culture of policing simply doesn’t match the needs of communities.

It’s also not a matter of a bad policeman or good policeman. Indeed, this is not about individual people. It’s about a system, an institution, that is responding in ways that don’t actually make sense for the people they purport to serve. We hear the police tout the notion of being a guardian or a warrior in communities. But we don’t need guardians if the guardians kill us, and we don’t need warriors at war with the people needing protection.

We have been convinced that we will not know safety if we do not know the police. But says who? They are the thin line between a complete overhaul of the system and a tinkering at the edges of the status quo. And this is why people double down on their power. But we must be able to conceive of another way to respond to conflict that is not rooted in negative power—we have done it elsewhere, in homes, in classrooms, in communities. We have seen models of restorative justice, in which communities manage conflicts that arise among themselves, without needing the intervention of a government agency. We have to be honest and imaginative about where we are and where we need to be.

Like all institutions, policing wants to convince you that it is permanent, the only way forward, and in its best form now. But the truth is obvious.

In January 2015, Leon Kemp, Reggie Cunningham, Brittany Packnett, Johnetta Elzie, and I, a group who met during the protests and had since begun collaborating on solutions, realized that we were playing a game with only half of the pieces, a quarter of the board, and without knowing the rules, if there were any. In the days following the initial protests, we all heard more and more stories shared on the streets and through Twitter of black men, women, and children who were victims of police violence. It was becoming clearer that our collective demand that officers be indicted and hope that they were convicted was being roundly ignored. There was no accountability anywhere across the country, and we were trying to understand the how and why of it. Understanding the scope of what we were grappling with seemed like a necessary starting point.

What we quickly realized was that the federal government could tell you how many inches of rainfall there was in rural Missouri in the 1800s, but it could not provide reliable statistics on the number of people the police killed last year, let alone all the other forms of police violence impacting communities.

Around this time, Samuel Sinyangwe, a young policy expert and data scientist in San Francisco, reached out via Twitter with an interesting proposal. He’d been engaged in policy, and though he hadn’t been with us in the streets in Ferguson, he knew that if the protests were ever to have substantive impact, we’d need data to inform a set of demands that had yet to emerge. He thought it would be possible to build the first comprehensive database and analysis of fatal police violence in the United States, including data on all types of violence that resulted in death. He wanted my help. A tweet turned into a phone call and then into Sam becoming part of our team.

The difficulty with building the database was that the police actively r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Author’s Note

- One: On Hope

- Two: How Am I Supposed to Respond to Murder?

- Three: The Problem of the Police

- Four: Bully and the Pulpit

- Five: The Choreography of Whiteness

- Six: I Was Raised By Magic

- Seven: Taking the Truth Everywhere

- Eight: I Can Remember Her Now Without Sadness

- Nine: The Friend That’s Always Awake

- Ten: Out of the Quiet

- Eleven: On Organizing

- Twelve: Letter to an Activist

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright Page