- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

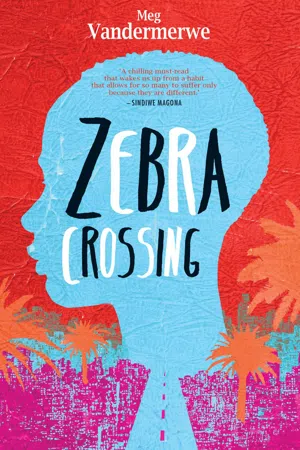

Zebra Crossing

About this book

Ghost. Ape. Living dead. Young and albino, Chipo has been called many things, but to her mother – Zimbabwe’s most loyal Manchester United supporter – she had always been a gift.

On the eve of the World Cup, Chipo and her brother flee to Cape Town, hoping for a better life and to share in the excitement of the greatest sporting event ever to take place in Africa. But the Mother City’s infamous Long Street is a dangerous place for an illegal immigrant and an albino. Soon Chipo is caught up in a get-rich-quick scheme organised by her brother and the terrifying Dr Ongani. Exploiting gamblers’ superstitions about albinism, they plan to make money and get out of the city before rumours of looming xenophobic attacks become a reality. But their scheming has devastating consequences.

Set in the underbelly of a pulsating Cape Town, Meg Vandermerwe’s Zebra Crossing is an arresting debut and a bold, lyrical imagining of what it’s like to live in another person’s skin.

On the eve of the World Cup, Chipo and her brother flee to Cape Town, hoping for a better life and to share in the excitement of the greatest sporting event ever to take place in Africa. But the Mother City’s infamous Long Street is a dangerous place for an illegal immigrant and an albino. Soon Chipo is caught up in a get-rich-quick scheme organised by her brother and the terrifying Dr Ongani. Exploiting gamblers’ superstitions about albinism, they plan to make money and get out of the city before rumours of looming xenophobic attacks become a reality. But their scheming has devastating consequences.

Set in the underbelly of a pulsating Cape Town, Meg Vandermerwe’s Zebra Crossing is an arresting debut and a bold, lyrical imagining of what it’s like to live in another person’s skin.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Oneworld PublicationsYear

2014eBook ISBN

9781780744315Subtopic

Literatura generalEleven

Saturday morning. Early March. Five months since George and I arrived in Cape Town. A hundred and twenty-five days until the World Cup kick-off. None of us has been the same since the night of George’s attack. Now, waiting for the World Cup doesn’t fill us with excitement. It fills us with trepidation. It seems the threats spat at George by the ticket inspector have begun to be heard by others.

‘Let’s go to the internet café,’ David says. He will teach me about Google Earth.

Together we walk to the café on the corner. It is the cheapest, set up in a corridor of a building and costing just five rand for thirty minutes. We pay our money and sit at a monitor.

‘It works by satellite. See, if you zoom you can see the exact spot in Beitbridge where your house is.’

‘Was.’

‘Sorry, was. But still, isn’t it incredible, Chipo? Jeremiah has taught me all about it. Look, there’s our old school. And there is the tree where Peter was chased by the vice-principal for kicking a soccer ball at his head. Do you remember?’

And Mama’s grave? But I do not ask to see that. Instead I tell David that I want to see the Old Trafford soccer ground in Manchester.

‘Can we?’

‘Just watch.’

A few clicks on the keyboard and mouse. There it is. The pitch and buildings I know our mother would have given anything to visit. David and I wait for the image to grow clear and solid. It looks very small.

‘One day, I will take you to the real Old Trafford, my children. We will walk where the greatest red shirts have.’ This memory of Mama’s promise, as I helped her to stir the Seven Days fermenting in buckets, one happy evening, long before our troubles started, comes to me as I watch David trying to enlarge the image further.

‘Look, you can see the stands and individual seats!’

Over the next month, for five rand a half-hour, David and I ‘visit’ the original Old Trafford many times. Also New York’s Statue of Liberty. Paris and the Eiffel Tower, London and Buckingham Place. David says it is like looking through ‘God’s spectacles’.

‘Imagine if they can create a computer programme that allows you to see into the future,’ David says. ‘I suppose the American military will like that. It is they who developed this technology, you know. For spying and what-what. It would be good, too, to know if we are to take these xenophobic rumours seriously.’

Imagine, I repeat. Imagine if one can look into the future. Not just of countries. But into our own futures too.

‘Have you ever been to the townships?’

‘No, never.’

‘George says that the people who want us to leave live there. He says that he cannot believe it. We are all Africans, and yet they see us as worse than colonisers.’

I watch Jean-Paul carefully measure the fabric. He marks it with his tailor’s chalk and then cuts it, piece by piece, shape by shape. I think he is making a jacket. So far he has shown no emotion. Has he heard the rumour? Does he not care?

‘Jean-Paul, they say we have until the World Cup final to leave. We can stay until then but after that they will drive us back across the borders.’

‘Where did George hear that?’

‘From the ticket inspector who attacked him.’ I pass Jean-Paul the pins. ‘But also at the restaurant. From the waiters who take the train in from Observatory. Complete strangers have started approaching them. They say, “We are giving you until the World Cup final. After that, you better go home.” And it’s not just on the trains. Peter’s girlfriend, Aneni, says that a Xhosa woman, a woman at the hotel where she cleans, said to her, “Sorry for you. When the World Cup is finished, you will burn.”’

Still Jean-Paul shows no emotion. Does he not believe me?

‘George says we are probably safe in the city, though. That it is the foreigners living and working in the locations who must worry. A lot of Somalis have tuck shops there, apparently. Here we are among our own. Is that why we don’t live in the locations but in town? To be among our own?’

‘Perhaps. But I live in town because that is where my clients are.’

I think about Luthumba, Beitbridge’s location. It stood a few minutes outside the town centre. I wonder about Cape Town’s locations. Khayelitsha. Gugulethu. Nyanga. They don’t sound or rhyme like anything. What are they like? Their homes? Their schools? Markets? Soccer pitches? Surely the same as ours?

Mama once told me a story about when she was a girl.

‘There was a bad drought. Not a drop of rain for almost three years, mwanangu. Things became scarcer and scarcer. First fresh goods, fruit and whatnot. Then meat. The women started to fight at the markets and in the shops for mealie meal, for samp and rice. Neighbour versus neighbour. Sister versus sister. Mothers against daughters.’

I told Jean-Paul the story. He shook his head. But there was no drought here. Wasn’t there enough for everyone, even us foreigners? Jean-Paul did not look at me. He carefully pinned the front and back pieces of fabric together. I was growing frustrated by his silence.

‘When we are scared for our livelihoods, we can do terrible things,’ he replied finally.

‘Were you here the last time? In 2008?’

‘Yes.’

‘So what do we do?’

‘We wait.’

I want to talk to Jean-Paul about this, but I can see he is in no mood to discuss such matters. He works silently, his forehead creased into a frown. I pull a chair to the window and sit down.

Below in the street, how many were visitors? Tourists or those just passing through Cape Town? Foreigners like us, yet everyone greets them with open arms because they have money.

Rent day. It always puts George in a foul mood. He says he would rather be hanging on to his hard-earned wages than giving them away to fat-bellied South African strangers. But Peter is strict. The rent is not allowed to be late. Late rent means there is a good chance we will be put out onto the street.

Today George is in an even worse mood than normal when he hands over the blue and pink notes. He says that last night Mr Ross made him clean human shit off the pavement in front of the restaurant. He says he has had enough of Mr Ross’s orders, and something more lucrative must come soon.

‘If the stinking manure does fall from the cart in July, I don’t want to have made this journey for nothing.’

Everyone has been talking about the new rumours. They seem to have infiltrated every community – the Zimbabweans, the Congolese, the Cameroonians, Malawians, Nigerians, Somalis. Before, we looked forward to the arrival of the World Cup. It was something to be celebrated. But we no longer trust it. Still, no one is talking about leaving South Africa yet. I think they are hoping to get a slice of all the tourist cash that everyone has been promised. George, too, is hoping to profit.

‘Maybe their money will be the answer to all our troubles,’ he told Peter and David last week. ‘We will make enough money to go home and live easy for a while.’

Then one evening George comes home with more bad news. Luc from the restaurant has gone.

Luc’s job was to stand outside Tortilla and stop the street children from putting the tourists off their refried beans and beer.

‘But on Monday he didn’t turn up for work.’

Three nights passed and still no Luc. He wasn’t answering his cellphone either, says George. Mr Ross ranted a lot. He said Luc had better stay away because as soon as he stepped through the door, he would fire his black backside anyway.

‘But word has come from Luc’s cousin today. He’s been refused his residence permit. When he went to Home Affairs to get his six-month update, they arrested him on the spot. This is how they are now doing it. Art of surprise. They are putting us in prison until the deportation plane leaves. A normal prison with common criminals. That way, they are sure to wash the taste for South Africa from our mouths.’ George sits down and lights a cigarette.

‘But Luc has a wife and two children in South Africa,’ David replies. ‘His wife’s decision is still pending, but he is on a plane back to the Congo. So now their family is split apart?’

George nods.

David’s forehead is creased like a shirt in need of ironing. Jean-Paul is from the DRC, like Luc. Will he be put on a plane back to Kinshasa too? I ask.

‘Don’t worry Chipo,’ David says, ‘Jean-Paul has already been here ten years and has asylum-seeker status.’

‘It is you and I who should worry,’ George tells me. ‘Our six months will be up in two weeks’ time.’

When George and I went back to Home Affairs, George was even more nervous than the first time. Me too. But everything went smoothly. We didn’t get any nasty surprises, and the lady behind the counter told me my decision was ‘still pending’.

Until Home Affairs makes its final decision, Peter says we are on borrowed time. But the good news is that some people can wait as long as four years to hear the outcome of their application. There is a backlog at Home Affairs, says Peter, and not enough motivated staff to sort out the piles of paper. So we might be OK. In four years we could achieve a lot.

George doesn’t agree. He says that even though we received another six-month permit, it doesn’t mean much because the World Cup is coming. And that might be the end of us. I know he is combing his brain trying to figure out a clever plan to earn lots of rand fast. But so far he is still stuck sweeping dead cockroaches out of Mr Ross’s kitchen and washing street children’s shit off the pavements.

‘We could try to sell something?’ Peter suggests. ‘Some foreigners have started to do a side trade in World Cup memorabilia.’

This is true. I see them leaving President’s Heights early in the mornings with miniature South African flags to sell to the motorists travelling to work.

George shakes his head. ‘Ha, waste of time. Selling flags is not going to save anyone’s backside. And you know what is most pathetic of all?’ George raises his voice so that Jeremiah, who is standing near the window, can hear. ‘Those foreign Africans who have started wearing Bafana Bafana jerseys like they are natives.’

Jeremiah flinches like someone has just spilt boiling tea on his hand. He is wearing the green and yellow national team shirt with the collar turned up.

‘They think that if they wear South Africa’s team jersey, that makes them real South Africans. They think it will keep them safe. Ha. No one cares what soccer shirt you wear. They only care what your “pass book” says.’

That’s what George has started to call our Home Affairs papers. Pass book. He says that when the whites still ruled South Africa, all the blacks had to carry a pass book. The pass book said who could go where and when.

‘Exaggeration,’ says David. ‘Our documents are no apartheid pass book.’

But George goes on and on. It is rare for him to show that he too was no fool at school before lack of money forced us to stop attending.

‘We are going to Fabric City.’ Jean-Paul is pulling on his coat when I come in.

Fabric City? In Woodstock? I want to talk to Jean-Paul about everything. About pass books. About Luc. About whether to worry now that the rumour has spread. But I know that he never goes anywhere if he can help it. So this must be important. I go fetch my jacket and together we walk down to the bottom of Long Street to catch a minibus taxi.

When we reach the corner of Sir Lowry Road, the taxi door slides open and Jean-Paul and I get out.

‘What is that noise they are always playing?’ Jean-Paul grimaces as the taxi speeds off, the windows rattling with local hip-hop. ‘Shout...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Prologue

- One

- Two

- Three

- Four

- Five

- Six

- Seven

- Eight

- Nine

- Ten

- Eleven

- Twelve

- Thirteen

- Fourteen

- Fifteen

- Sixteen

- Seventeen

- Eighteen

- Nineteen

- Twenty

- Twenty-one

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Zebra Crossing by Meg Vandermerwe in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.