- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

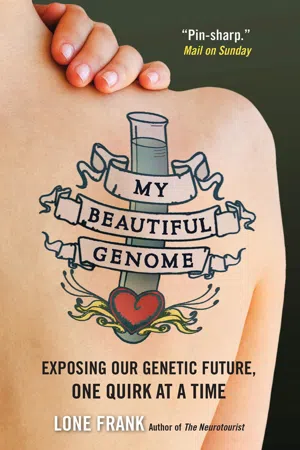

About this book

Internationally acclaimed science writer Lone Frank swabs up her DNA to provide the first truly intimate account of the new science of consumer-led genomics. She challenges the business mavericks intent on mapping every baby's genome, ponders the consequences of biological fortune-telling, and prods the psychologists who hope to uncover just how much or how little our environment will matter in the new genetic century - a quest made all the more gripping as Frank considers her family's and her own struggles with depression.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access My Beautiful Genome by Lone Frank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Biografie in ambito medico. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicinaSubtopic

Biografie in ambito medico1

Casual about our codons

Get to know your DNA. All it takes is a little bit of spit.

23 ANDME WEBSITE

“THERE HE IS – that’s him!”

The man next to me rolls his eyes and tips his head in the direction of an elderly gentleman with an odd bent who is slowly making his way across the lawn beyond us. It’s James Watson, the man I’ve come to this conference at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, near New York City, to meet. He’s wearing a grass-green pullover and a fire-engine-red bush hat.

“Big Jim!” my interlocutor notes with a broad smile. “If you want to talk to him, you’ll have to be aggressive. He’s pretty talkative up to a point, but he’s become a bit skittish with reporters.”

That’s understandable. Watson, who together with his colleague Francis Crick, is credited with uncovering the chemical structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, had recently experienced an annus horribilis. In 2007, he had run foul of the media machine, and lost some of his luster as a Nobel Prize winner, during a book tour in Britain to promote his latest autobiography, Avoid Boring People. In an interview with the Sunday Times, he had remarked that he thought the prospects for the African continent were gloomy, because the intelligence of blacks was lower than that of the rest of the world’s population. He went on to say he hoped everyone was equal, but that “people who have to deal with black employees find this not true.” He also managed to assert that it would be perfectly okay if, on the basis of prenatal testing, a mother-to-be decided to abort a fetus that might have a tendency toward homosexuality. Why not? That sort of choice is entirely up to the parents.

These were opinions Watson had aired in various iterations many times before, but printed in black and white, in a major newspaper, they could no longer be tolerated. Enough was enough. Though a small group of academics defended Watson and tried to explain his statements, the remainder of his book tour was canceled. The Nobel laureate went home to his laboratory at Cold Spring Harbor, where he had been pleasantly and securely ensconced in the director’s chair since 1968.

But the furor wouldn’t die. Soon after his return, a contrite Watson issued an apology with a built-in disclaimer – it wasn’t really what he meant, and blacks are certainly fine people – but the protests continued. Finally, the laboratory’s board stepped in. At seventy-nine, Watson accepted an emeritus position and enforced retirement. Not that he was thrown out: he still retains a wood-paneled chancellor’s office, in whose antechamber a secretary guards the doctor’s calendar with the ferocity of a dragon. And he still shuffles about the lawns and supplements his role as the godfather of genetics with a passion for tennis.

“The most unpleasant human being I’ve ever met,” the well-known evolutionary biologist E. O. Wilson is on record as having said of Watson. And when the old man wasn’t being called a racist, the word “sexist” took its place. Watson had a reputation for not accepting female graduate students in his group and for making statements to the effect that it would be an excellent innovation if we could engage in a little gene manipulation to ensure future generations of women are all “pretty.”

With this nagging in the back of my mind, I pull myself together and trail after Dr. Watson, notepad in hand.

“What do you want?” he asks nervously. “An interview?”

Watson fixes on me from behind a pair of glasses that make his eyes look like a pair of golf balls. Their assessment does not, apparently, fall in my favor.

“I don’t have time,” he says softly, turning away. “I have to go home for lunch. I’ve got guests I need to talk to. Important guests.”

He looks around impatiently, as if for someone to come and save him.

“Just ten minutes,” I plead, but this time I receive a heavy sigh and a sort of wheeze as a reply. When he remains standing there, oddly indecisive, a kind of impertinence takes over, and I mention almost at random one of the lectures from the day before, on genes and schizophrenia. He’s hooked. Watson abruptly draws me inside, into the empty Grace Auditorium, where the conference on personal genomes is taking place, and sits down in one of the front rows.

“My son has schizophrenia,” he says. I nod in sympathy – I had heard the tragic story of his youngest son, Rufus. Immediately, Watson begins to mumble. He whispers and snuffles, but his eyes are clear, without a hint of the confusions that often come with old age.

“With respect to genetics, it’s still a huge motivation for me to see that this disease is understood. If you ask me what I’d like to see come out of the genetics revolution, it is this: I want to see psychiatric illnesses understood and explained. We have no idea what’s going on. Imagine: there are a thousand proteins involved in every single synapse through which a nerve cell transfers impulses to another. And there are billions of them.”

As Watson warms to his subject, I run with his change in mood. My own greatest interest, I hurry to tell him, is behavioral genetics, in understanding how genetic factors take part in shaping our psyche and personality, our mental capacities, and our behavior as a whole. It is known that heredity is involved not only in our temperament and mood, but in complex matters such as religiosity and political attitudes.

Yet how could a slight variation in the proteins that sail around our brain cells possibly lead to a preference for right-wing or left-wing politics? At one end, you have some strings of genetic information; at the other, a thinking, acting person; and in between, a black box. A box that researchers are only now beginning to prise open.

His golf-ball eyes harden their lock on me. “Mental capacities?” Watson then says in a thin but sharp voice. “Yes, they are interesting, of course – academically interesting – but you have to understand that disease is always the winner, when research money is being distributed. And it has to be that way... there are people out there suffering!”

He wheezes again. Whether it is to clear his throat or his thoughts, I am not sure.

“Truth be told, I don’t believe there is a chance that the mysteries of schizophrenia will be solved for another ten years. At least ten years.”

Many would agree with Watson’s assessment. In 2009, a small army of researchers announced the results of three gigantic studies, involving fifty thousand patients scattered across many countries, into the genetic cause of schizophrenia, and they had found very little. In the New York Times, Nicholas Wade bluntly called the disappointment “... a historic defeat, a Pearl Harbor of schizophrenia research.” The only firm result: no particular genes could be found that determine whether a person develops schizophrenia or not. Furthermore, it is presumably not even the same genes that are involved in all patients.

Here at the Cold Spring Harbor conference, the participants have been discussing the great mystery of genetics: the issue of the missing heritability. This is the “dark matter” of the genome. Again, take schizophrenia. Scientists know from countless twin and family studies conducted over decades that the disease is up to eighty percent heritable, but, despite the army of researchers’ thorough studies, with tens of thousands of patients, only a small handful of genetic factors have come to light. Altogether, these factors explain just a measly few percent. So where are the rest to be found?

“Rare variants,” whispers Watson, as if he were making a confession. “I think it lies in rare variants, genetic changes that are not inherited from the parents but arise spontaneously as mutations in the sick person. Listen: you have two healthy parents and then a child comes along who is deeply disturbed. So far as I can see, it cannot be a question of the child having received an unfortunate combination of otherwise fine genes. Something new has to happen. We have to get moving to find this new thing, and my guess is that we need to sequence the full genome of, perhaps ten thousand people, before we have a better understanding of the genetics in major psychiatric diseases.”

I ask how it feels to have your genome laid out for everyone to see on the Internet, but Watson pays me no heed. He is lost in his own train of thought.

“Just think about Bill Gates. This man has two completely normal parents but is himself quite strange, right?”

Fortunately, Watson continues before I’m forced to offer a reply.

“No debate,” he says. “Bill is weird. Maybe not outright autistic but, at least, strange. But my point is that we cannot know in advance who we as a society need. Who can contribute something. Today, it appears that these types of semi-autistic people who are good with computers are really useful. I don’t have a handle on all the facts, but I could imagine that in a hundred years, as a result of massive environmental changes and that sort of thing, we human beings will have a much higher mutation rate than we have had up until now. And with more genetic mutations, there will be a greater variation among people and, thus, the possibility for more exceptional individuals.”

He gives me a quick sidelong glance. “There are very few really exceptional individuals, and most people by far are complete idiots.”

There is a little pause.

“But success in life goes together with good genes, and the losers, well, they have bad genes.” Watson stops himself. “No, I’m in enough trouble already. I’d better not say more.”

His self-imposed silence lasts five long seconds.

“I mean, it would be good if we could get a greater acceptance of the fact that society has to deal with losers in a sympathetic way. But that’s where things have gone wrong – that we would rather not admit that some people are just dumb. That there are actually an incredible number of stupid people.”

I suddenly recall one of Watson’s classic remarks, that the proportion of idiots among Nobel Prize winners is equal to that among ordinary people. Of course, I don’t mention it. That would be crude and insolent, and though I tend to be brutally honest, I know not to push my luck with the old man. Instead, I ask how it feels to be able to look back on the almost incomprehensible advancements that he helped to kick-start almost sixty years ago.

“I never thought that I would have my own genome sequenced – the whole thing mapped from one end to the other. Never. When I was involved in the Human Genome Project, where over several years we mapped the human genome as a common resource, that sort of personal genome seemed entirely utopian. And even when young Jonathan Rothberger from 454, the sequencing company, suddenly offered in 2006 to sequence my genome, it sounded crazy. But they did it.”

The dreamy gaze disappears.

“Today, it’s about getting every genome on the Internet, because if you want to know something about your genome, you have to have a lot of eyes looking at it. That’s where the money should be going, to get more and more genomes published, so researchers can analyze them and squeeze more knowledge out of the information. Do you know what? They should sequence more old people, because for obvious reasons we are more willing than young people to put our genomes on the Net for public viewing.”

Once again, I see the chance to probe Watson about his genome. I want to know how it feels to scrutinize and immerse yourself in your own genetic material. To have made already the journey that I’m hoping to take. “Has knowing your own genome affected you?”

“No, I don’t think so. To be honest, I don’t think much about it.”

“What about the gene for ApoE4?” I ask cautiously. From the beginning, Watson said that he did not want to know whether he has this well-known variation of the Apolipoprotein E gene, which multiplies the risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease.

“No, because then I would fret about it, whether it was incipient dementia every time I couldn’t remember a name or something like that. Hah! As things stand, I only worry about it half the time.”

Since his genome is on the Internet, I wonder whether he really doesn’t know the truth or his professed ignorance is pure coquetry. I note out loud that there is no reason to remain ignorant, since he is already eighty-three years old – if he doesn’t suffer from dementia now, he probably never will.

“You haven’t quite understood,” he says, slightly hurt. “Dementia can easily strike in your nineties; it happened to my own grandmother. She was born in 1861 and died when I was twenty-six. Wonderful woman, by the way. I must tell you...” He turns around to face me. “I know many men in their eighties who are still razor-sharp, but I don’t know many role models who are over ninety. Something happens to most men between eighty and ninety.”

For a moment, I think that he has revealed a sense of humor, but before I laugh I catch the expression in his eyes. He is utterly serious.

“But there is something else. I believed that, as a white male of European origin, I could tolerate milk and have always drunk it. And I’ve eaten ice cream, lots of ice cream. But my genome reveals that I am partially lactose-intolerant. Today, I only drink soy milk and must admit that I actually have fewer gastric problems.”

This was, perhaps, too much information.

“Everyone should have this kind of knowledge from birth, so mothers could make sure their children have the best possible diet.” He muses on another example: heart attacks and hypertension. “I also have a gene with reduced activity that makes me metabolize beta blockers poorly. Because I have high blood pressure, the doctors had already given me medicine. With this genetic knowledge, it was suddenly not strange that the pills just made me fall asleep. One out of every ten Caucasians has a genetic variation that makes beta blockers ineffective for them. Everyone should be screened for that kind of stuff, right?”

Suddenly, Watson changes track.

“We’ve reached a point where we have to ask ourselves how much we can defensibly contract out to private companies. I’m an academic, dammit, and I would rather see my friends’ genomes mapped by an academic lab like the Broad Institute in Boston or the British Sanger Centre than by some company. These outfits come and go and have no real interest in the science,” he says, staring vaguely in the direction of the larger-than-life-size portrait of himself that is the auditorium’s only decoration. The artist looks to be an admirer of the British painter Lucian Freud and, like his role model, has depicted his subject with every fold of skin and liver spot.

The living Watson slumps a bit in his chair. He looks infinitely tired, an old turtle more than an old man. He shakes his head.

“I don’t know where we end. Think that we’ve come so far that everyone can not only have his genome sequenced but can have it done by Google.”

He relaxes his arms over the chair and falls into a reverie.

“Are you going back to Denmark now?” he asks out of the blue, for the first time in a directly friendly tone. I answer in the affirmative.

“Poor girl. That country is the saddest place I’ve ever been. Before I went to the University of Cambridge, I was there for a whole year, doing virus research for the National Serum Institute in Copenhagen. As I remember it, the sun never came out once.”

THE YEAR JAMES Watson spent in Denmark was three years before the breakthrough that transformed him forever into Big Jim and revolutionized humanity’s understanding of biology. As his colleague Francis Crick shouted that evening after the two had finally grasped the helix form of the DNA molecule and tumbled into the Eagle Pub in Cambridge: “... we had found the secret of life.”

In his classic account, The Double Helix, Watson describes how he hit on the structure one day when he was sitting in the lab playing around with cardboard models of the four bases that serve as the genome’s universal building blocks: Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine, and Thymine. At once, the young but intensely ambitious researcher realized how these bases must fit together in fixed pairs: that A and T combine with two weak hydrogen bonds, while G and C bond with three. It also became obvious how the bases had to face each other and, thus, hold the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Prologue: My accidental biology

- 1. Casual about our codons

- 2. Blood kin

- 3. Honoring my snips, in sickness and in health

- 4. The research revolutionaries

- 5. Down in the brain

- 6. Personality is a four-letter word

- 7. The interpreter of biologies

- 8. Looking for the new biological man

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index