![]()

1

Introducing the Victorians

The Condition of England, on which many pamphlets are now in the course of publication, and many thoughts unpublished are going on in every reflective head, is justly regarded as one of the most ominous, and withal one of the strangest, ever seen in this world.

Thomas Carlyle, Past & Present (1843)

New Queen, new age?

On 28 June 1838, almost exactly a year after the death of her uncle, King William IV, Queen Victoria was crowned in Westminster Abbey. William IV’s coronation in 1831 had been the first to feature a procession by carriage through the streets of London. Victoria followed suit but took a far longer, almost circular, route. Londoners, as well as nearly half a million visitors to the capital, observed the royal parade in all its glory. Nobles and dignitaries from around the world were present to demonstrate their respect for the new Queen. Yet press reports often chose to focus not on aristocratic wealth or royal grandeur but on ‘the dark and heaving masses’ who lined the route. These crowds were ‘full of eager expectation’ but also carried a hint of threat in this politically unsettled era. Would the eighteen-year-old Queen be overwhelmed by the sight of these thronging masses? The Duchess of Sutherland was on hand to help her ‘conceal… her emotions’ and the procession’s first port of call, the Ordnance Office, was manned by Royal Artillery in case ‘the vast masses that pressed on all sides, deepening and accumulating’, should give in to the unruly instincts of the mob.

This parade was the high point of an otherwise inauspicious coronation. The ceremony itself was unrehearsed, disorganized, and mishandled (the modern, micromanaged event, seen at the coronation of Elizabeth II, was, despite its medieval trappings, invented only in 1902). The young Queen spent much of the five-hour service, during which she wore three dresses, eating sandwiches from the altar of a side chapel. The traditional coronation banquet was not even held, and the mood was dampened by news of anti-royal protests held in Northern English cities such as Manchester and Newcastle. This was a ceremony too ostentatious for radicals, who required that the will of the people, not the monarch, be placed at the centre of public life, but too unspectacular for Tories, who demanded pomp to demonstrate royal authority.

This was also among the most unlikely coronations in British history. The young Victoria had been fifth in line just a few years earlier, but would have slipped further from the throne if any of her father’s three brothers had fathered children who survived beyond infancy. Only a series of accidents – a strange destiny – had led to the events of 28 June. Many of Victoria’s subjects believed strongly in the power of destiny (or ‘providence’ as Victorian religion styled it) to define personal and national fortunes, and by the time the Queen’s fate had taken its course she was not just monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, Princess of Hanover, and Duchess of Brunswick but also Queen of vast colonies and Empress of India. Britannia ruled an extraordinary number of waves.

As with most supposed destinies, there were substantial cracks in the impressive facade. Victoria’s reign was as troubled as her coronation. Her accession took place at a time when the nation she ruled was divided. The gulf in wealth and resources between rich and poor was large and constantly increasing, while conflict between European powers remained probable despite the fragile settlements that followed the Napoleonic Wars. Disagreement raged over the nature of state and society: in most circles, ‘democracy’ remained a dirty word, while in some it was emerging as the rallying cry for a reformed politics, free from the elite domination and corruption of the old regime.

The young Queen, less conservative than her Tory uncle William IV, gave such hope to the champions of democracy that radical ballads were sung in her honour. In a parliamentary system where Whigs often favoured values that might loosely be termed liberal and Tories stood for conservative ideals, Victoria was a Whig monarch, with a Whig government. However, in 1838, it was not clear what direction the following decades would take. Would the ‘deepening and accumulating’ masses rise, as they had in France fifty years before, to demand a more substantial redrawing of politics than had been provided by the meek and mild Reform Act of 1832? Or would the powerful Tory contingent in Parliament embark on its golden age, strengthened by the controlled reform of the early 1830s, with its claim to represent Britain (symbolically rather than democratically) more credible than ever before?

The spell cast by the word ‘Victorian’

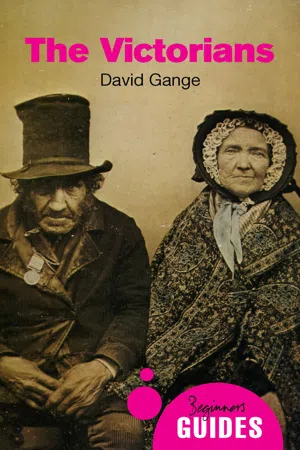

This Queen’s name gives us a term that conjures many vivid images: lace and crinoline, top hats and petticoats, steam trains and horse-drawn cabs. It suggests child labour in factories and mines, corporal and capital punishment, street crime, acceptance (even approval) of domestic abuse, and a stern religion that damned all but a few to hell. It suggests the mundane violence of the strap-wielding father and the infamous cruelty of Jack the Ripper. But maybe ‘vivid’ is the wrong word for these images since they reach us in shades of sepia and grey that befit the nostalgic and repressed Victorians of our imagination. This is the first era for which we possess a photographic record, and the peculiarities of the Victorians’ efforts to negotiate their strange new technology informs our view of them. Morbidly, they photographed their dead. Earnestly, they did not dare to smile when photographed. Rigidly, they only very rarely betray small informalities in front of the lens. Lengthy exposure times necessitated the stiff formality that we too readily assume the Victorians to have embodied in everyday life.

In photographs, we see everything of these people except the colours; everything except the unguarded expressions that convey character; everything but what went on in their heads. These photographs impress a caricature on our memories: an era that is close to us in time, yet in ethos and atmosphere is everything we are not. The Edwardians invented this image of the Victorians as their opposites, the ‘other’ against which they defined themselves. We have allowed this habit to persist. Where we nurture children, the Victorians exploited them; where we pursue equality in class and gender, the Victorians protected institutions that sustained inequality; where we are spontaneous, liberated, and funny, the Victorians were earnest, uptight, and humourless.

Many Victorians were, however, far more radical and progressive than those self-conscious Edwardians who made their name mud. Even in photographs, their formality could occasionally disappear, leaving strikingly modern individuals, as images recently discovered in the Northumberland Archives have demonstrated. In other words, it was because some Victorians defended institutions that oppressed the poor, women, or children that other Victorians assaulted these institutions with an aggression and enthusiasm that had never been seen before. Far from revelling in child exploitation, many Victorians demonstrated unprecedented commitment to the rights of children to education and protection from hard labour. The chief reason that a patriarchal, repressive, and literalist religion was defended with great vigour was that its worldview was now rivalled and threatened by liberal theologians, geologists, physicists, and, later, evolutionary biologists.

If we are to understand this strange period, we must do so through these contrasts and oppositions. We must recognize that the Victorians were not defined by what they agreed on, but by what they argued over. This was a society in which public debate took place on an unprecedented scale, drawing in far more of the population than ever before. The periodical press, in which much of this debate took place, was vast and flourished on a scale that we (with our relatively short list of major magazines, newspapers, and journals) find difficult to imagine. Across the century, the number of separate periodical titles cannot be counted in the hundreds, or even the thousands, but exceeded 130,000. In the millions of pages therein, countless questions were discussed countless times. Above all, this was a society that argued. It debated its every innovation. It interrogated the moral purpose of the sciences and the scientific basis of morals. It even argued about whether or not this was the most argumentative time and place in history. In disputes such as these, we will find ‘the Victorians’, a subtle and contradictory population, far more thoughtful, three-dimensional, and subversive than our stereotypes allow.

The Victorian self-image

One topic of intense argument in Victorian Britain was the term ‘Victorian’ itself. By the middle of Victoria’s long reign, this adjective cast its spell over Victorians as much as it does over the twenty-first century. During the first twenty years of the period, the term ‘Victorian’ had not been in common use. Its rare appearances came largely in satire: it was used to mock those arrogant enough to assume that their own eccentricities could characterize an ‘era’. From 1857 onwards, however, the term proliferated, its usage triggered by the twentieth anniversary of Victoria’s accession. By the 1880s, it was subject to intense dispute throughout society.

From 1857 onwards, most who commented agreed that to speak of a Victorian age made sense. They insisted that the 1830s had not just seen the accession of a monarch, but also marked a distinctive break in British history: ‘old things passed away, and behold, all things became new’. The 1857 article on ‘Victorian Literature’ from which this quote comes listed a host of things that made the 1830s into a ‘new age’ including the establishment of a railway network, the first instance of communication by telegraph (1837), the first steam-powered crossing of the Atlantic (1838), the first education grants, the introduction of a penny post, and the first matches (an important invention in cities lit by candle and gaslight). The author then listed the deaths, in quick succession between 1832 and 1836, of the major literary and philosophical figures of the preceding ‘age’: Goethe, Walter Scott, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charles Lamb, Hannah More, Jeremy Bentham, Thomas Malthus, James Mill, and Samuel Wilberforce (among many other celebrated names). With the Napoleonic Wars (1798–1815) a memory, and the ‘bawdy’ eighteenth century fading from view, writers such as the ‘Victorian sage’ Thomas Carlyle felt they had a chance to make a fresh start. For Carlyle, writing in 1837, there had been nothing noble in the frivolous eighteenth century at all until the ‘grand universal suicide’ accomplished in the French Revolution, which seemed to open up a new world – with new hopes and fears – before him and his serious-minded, Victorian, contemporaries.

VICTORIAN SAGES

This term describes a self-styled ‘cultural aristocracy’ who acted as guardians of Victorian high culture. They include:

• Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), author of On Heroes and Hero Worship (1841)

• Matthew Arnold (1822–88), Chief Inspector of Schools, author of Culture and Anarchy (1869)

• John Ruskin (1819–1900) author of Modern Painters (1843–60)

These sages wrote stylish books and essays that took society to task for lacking high ideals. Some of their more concise works still make great reading, but their elitism can cause discomfort. In current usage, ‘sage’ is a deliberately pompous term that draws attention to the self-importance of this all-male cast. Other thinkers – e.g. George Eliot (Marian Evans) and Harriet Martineau – were their equals as writers but lacked the sages’ social cachet.

This perception of a clean break persisted throughout Victoria’s reign. For instance, an 1888 essay in The Gentleman’s Magazine insisted that the 1830s were

A time of singular activity and innovation in all departments of life. The prolonged reaction produced by the wild excesses of the first French Revolution was at last exhausting itself. Ideas of political advance that had been put aside for more than a generation began once more to be ardently and irrepressibly entertained. Democracy began to feel its strength and to make its strength felt… ‘The world’s great age’ seemed beginning anew; ‘the golden years’ seemed returning. And in all directions, along with this political energy, both just before and just after 1832, there were accomplished new developments and signal discoveries.

This passage might appear triumphalist, yet it embodies the idea of contradiction and disagreement crucial to this argumentative moment. It even contains its own counter-argument by voicing, subtly, a key characteristic of the age: intense uncertainty. One repeated word is far more significant than it may at first appear: the great age ‘seemed’ to be beginning; the golden years ‘seemed’ to be returning. The article goes on to explore the ways in which appearances mislead; anyone reading about the Victorians will need to get used to this deceptiveness of surface appearances.

The question of whether improvements were real or illusory worried many Victorians. Increasing numbers of people from the 1830s onwards were painfully aware of the price paid for every incremental advance. This was an era of sensational social commentaries describing in vivid detail the horrific conditions that uncontrolled urban growth had generated; it was the era of novels, such as those of Dickens, which aimed to elucidate the experiences and meanings that lay behind the brute facts of social change, bringing the emotional consequences of poverty and hardship to general attention. This genre was soon given labels such as ‘social problem’ and ‘condition of England’ novel. In fact, this age might just as well be labelled ‘Dickensian’ as ‘Victorian’ given the influence of Dickens’s characters and themes over subsequent images of the time. In the rise of this socially astute literature and the foundation of large public bodies devoted to assessing the evils attendant on progress, the self-scrutiny characteristic of the age was thought through and institutionalized. ‘Victorian values’ of philanthropy, education, and enfranchisement were being formulated but so too were Victorian characteristics of domination, control, and patriarchal discipline.

For God and empire

With an apparent self-assurance tha...