eBook - ePub

The Woman Who Saved the Children

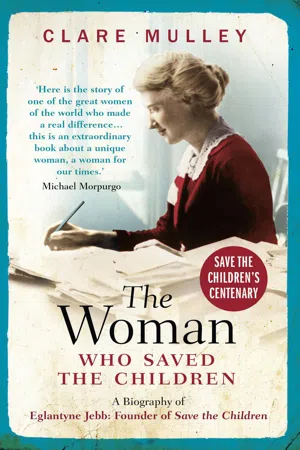

A Biography of Eglantyne Jebb: Founder of Save the Children

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Woman Who Saved the Children

A Biography of Eglantyne Jebb: Founder of Save the Children

About this book

The adventures and tribulations of Eglantyne Jebb, founder of Save the Children, and humble revolutionary Winner of the 2007 Daily Mail Biographer's Club Prize An unconventional biography of an unconventional woman. Eglantyne Jebb, not particularly fond of children herself, nevertheless dedicated her life to establishing Save the Children and promoting her revolutionary concept of human rights. In this award-winning book, Clare Mulley brings to life this brilliant, charismatic, and passionate woman, whose work took her between drawing rooms and war zones, defying convention and breaking the law. Eglantyne Jebb not only helped save millions of lives, she also permanently changed the way the world treats children.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Woman Who Saved the Children by Clare Mulley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Imagining Eglantyne, 2009–1876

The world is not ungenerous, but unimaginative and very busy.

Eglantyne Jebb, 1920

To succeed in life, we must give life,’ Eglantyne Jebb wrote as she searched for the way to give her life meaning. But Eglantyne did not ‘give life’ in the literal sense by becoming a mother. Despite social expectations she never married and she was not fond of children, the ‘little wretches’ as she called them, ‘the Dreadful Idea of closer acquaintance never entered my head’. Eglantyne chose to give her life to the pursuit of children’s welfare and human rights from a strategic distance. In doing so she helped to save the lives of millions of children left starving in Europe and Russia after the First World War. She also permanently changed the way the world considers and acts towards children. Her legacy, found both in the work of Save the Children, the world’s largest independent international children’s development agency, and the recognition of children’s rights as enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, now helps to protect the lives and support the life chances of millions of children around the world. This is giving life on a big scale, and yet despite helping to shape the modern world so dramatically through the lives of our children and the relationships between our generations, Eglantyne is all but forgotten today.

Self-portrait of Eglantyne losing important papers from her folder, Cambridge, c. 1906

The biographer also gives life indirectly, if in a much more modest way. I first came across Eglantyne when working as a struggling corporate-fundraiser for Save the Children. The difficulty with raising funds was not with the charity’s UK and international programmes, which being both innovative and effective screamed out for support. The problem was that so many people had stopped listening. The proliferation of children’s charities and international development agencies repeatedly approaching the same donors meant that the concept of ‘giving fatigue’ was itself getting rather tired. Feeling somewhat brow-beaten after a few unsuccessful weeks of proposal writing I found my faith in human nature restored by a reassuring line that Eglantyne had written eighty years earlier: ‘the world is not ungenerous, but unimaginative and very busy’. That’s it, exactly. Her words had a startling immediacy for me, and soon an uncanny ability to make even the most recalcitrant potential donors reconsider their priorities and spare a moment to be generous. Eglantyne’s genius was to catch people’s imagination, enabling them both to empathise with the human issue, and believe that they could contribute personally to a meaningful solution. She was, in short, inspirational. It was therefore surprising how absent she now seemed to be from the organisation aside from a paragraph on the website; a meeting room name; one photo on an office wall; an archive fact sheet; and her Smith Corona Portable typewriter, ‘such a bad one’ she had once moaned, now permanently parked in the archive.

The photograph must have been a Save the Children publicity shot; it fits the bill so perfectly. Eglantyne looks sober and handsome, if slightly uncomfortable, sitting posed at her desk. Except for a few wayward strands, her white hair is pulled back and pinned up, her lace collar sits softly over her smart dark jacket, and she gazes calmly down at her work, pen in hand. It must have been a wet morning; the shadow of rain is clearly cast on to the window-shutters and the light streaming in is diffused, lending a softness to the image which emphasises the femininity of this dignified campaigner for children’s welfare. Despite her concern for children’s rights, there is no touch of the suffragettes here. This photo hung above my manager’s desk: two admirable women sitting behind dignified piles of papers. My manager also epitomised the consummate feminine professional; a wonderful fundraiser, she was utterly organised, appropriately witty and marvellously persuasive with the great and the good. Most of us thought she was pretty much perfect, if anything perhaps slightly too perfect. Was she a modern reflection of this feminine, dedicated Eglantyne?

Inevitably a degree of distortion takes place when a single photograph comes to represent a whole life, a whole person, so it was good to see the pleasingly eccentric fact sheet, ‘Thirty-four things you didn’t know about Eglantyne Jebb’, compiled by Save the Children’s archivist. Like all good lists this one demonstrated a certain eccentricity in its composition as well as in its contents. Eglantyne, I learned, was ‘extremely warlike’ when a child, and as an adult often forgot where she was going and left her luggage behind on trains. She was a ‘shy furtive beauty’ who loved rock-climbing and dancing, wrote bad romantic novels, endured failed romantic hopes, and was not, at least at first, that great a fundraiser. Hurray: a flawed heroine after all. I began to feel a growing sense of empathy, affection and curiosity.

Later I found another image of Eglantyne to stick above my own desk. It is a self-portrait in pen and ink, a small scratchy picture that she once sketched on the edge of a letter to a friend. Eglantyne here is a woman in motion, head up, eyes forward, striding down a street. Two feet in sensible shoes, although with trailing laces, appear at either end of her long plain skirt, pulling it into a taut triangle as she powers ahead. Her hair is still up, but here pinned under a flat black Edwardian hat, a bit new woman, nothing too fashionable but perfectly acceptable. A long thin umbrella is tucked under her long thin arm along with a huge sheath of papers from which several sheets fly loose to drift unnoticed in her wake. It is not well drawn, but the better for that; it is Eglantyne knowingly, happily, imperfect. It is tempting to take this self-portrait as the real picture, but of course the truth is that there is not a single picture of anyone. Almost certainly, the more an image appeals to, or reflects, the observer, the less likely it is to represent the whole contradicting set of human truths that makes people so intriguing.

In 2001, showing remarkably less dedication to the cause than Eglantyne, who never had children, I stopped working to have a baby; now seemed a good time to idly find out more about this perfect–imperfect woman. Just two years after Eglantyne’s death her younger sister Dorothy co-authored the first biographical sketch of Eglantyne in her history of the early years of Save the Children. The book was called The White Flame after the nickname Eglantyne earned from admiring colleagues and supporters for her intense passion for her work towards the end of her life, and the quote on the title page read: ‘Her greatness was the greatness of the spirit.’1 All in it is a short and not impersonal portrait. A few other personal memoirs, some profiles in obscure anthologies as a Shropshire History Maker or a contender for canonisation, and a respectful biography, the wonderfully titled Rebel Daughter of a Country House, written by an aid worker who knew the Jebb family, soon followed.2 Eglantyne has since made a good press hook for several Save the Children anniversaries and, in some ways a thoroughly modern woman, she now has an online Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry and her own page on Wikipedia.

A digest of these various biographical sources provides a useful chronology, presenting Eglantyne’s life as short but full of endeavour and achievement. Fiercely intelligent and passionate about her social mission, Eglantyne experimented bravely with career and voluntary work. Defying the law and often the more conservative ideas of her own colleagues and supporters she evolved the temporary Save the Children grant-giving ‘Fund’ into a permanent and pioneering development agency. Full of charm and charisma she won over the Pope and the miners, the British aristocracy and the Bolshevik government, the prosecution at her trial for distributing information not cleared by government censors, and the fledgling League of Nations in Geneva. Publicly she was a huge success; her achievement in promoting both Save the Children and the applied concept of children’s universal human rights is undeniable. But personally the story is less clear. A compulsive writer, she failed to publish any of her novels and sometimes seemed to blur the distinction between reality and fantasy. Like all female students of that era she was not allowed to graduate, and she lasted less than a year in both of her paid jobs. She was repeatedly disappointed in love, quickly lost her health and more than once seemed to lose her mental grip.

This suggests some intriguing questions: What motivated Eglantyne? An intelligent and strikingly beautiful woman, why had she never married? Did she want children of her own, and was the fact that she was never a mother relevant to her passion for her cause? Or was her interest in children impersonal, and if so why? Were her regular illnesses, her emotional highs and lows, and the vivid imagination that was vital to her visionary work, in any way linked? And why did she often seem to wear such dour clothes? Who was this inspirational spinster in a brown cardigan and what, exactly, was going on in her head? The various published ‘lives’ of Eglantyne tend to focus on what she did rather than who she was, her ‘doing’ rather than her ‘being’. When her being was considered she was often presented, dead unmarried and childless at the age of just fifty-two, as having martyred herself for her cause. ‘She offered herself up as a sacrifice for her ideals,’ Ramsay MacDonald, the then British Prime Minister, eulogised in a speech to mark Save the Children’s tenth anniversary. Even her obituaries carried this theme, presenting Eglantyne as a ‘saint’, ‘humanity’s conscience’, and as having ‘lived on a different plane from ordinary mortals’. But the trailing laces and bad novels suggest she lived on the just the same plane as the rest of us. I suddenly wanted to release Eglantyne from the ‘tyranny of achievement’.

But just as I gained the time to find out more about Eglantyne by leaving work, I began to lose my sense of empathy by having a baby. Worse, I began to feel the antithesis of Eglantyne, who never had children and dedicated her life to the cause. This was irritating. Many modern biographers confess to a natural sense of connection with their subject. I compared my life to Eglantyne’s and found some happy similarities; we were both well educated and middle class, and not at first particularly gifted fundraisers. On the flip-side Eglantyne was an independent single woman who never had children, seemed to suffer from some kind of bipolar disorder, dabbled with spiritualism, became an opportunist human rights monitor and developed an international social movement of global significance. I was a stressed new mum. On the face of it there was not much to work on. However the seeming contradictions in Eglantyne’s life did strike a chord: here was a not obviously maternal woman giving up her freedom to devote herself to promoting children’s welfare. Ironically I was sneaking away from childcare to gain the time to work on my own project. I was almost an anti-Eglantyne, a sort of Ms Hyde to her Dr Jebb. I took some comfort in the romantic biographer Richard Holmes’ belief that ‘the true biographical process begins precisely at the moment … when this naïve form of love and identification breaks down. The moment of personal disillusionment is the moment of impersonal, objective recreation.’

Holmes, like many other respected biographers, deliberately set out to find his subjects, in his case first retracing the steps of Robert Louis Stevenson through southern France in ‘an act of deliberate psychological trespass’. I decided that it was time to go out and find Eglantyne.

Chapter 2

Meeting the Family, 1876–1894

They gravely sit on their old rickety chairs, and talk of poetry, articles, letters, affairs.

Eglantyne Jebb, 1888

Visiting Eglantyne’s Shropshire home, the rather romantic Lyth, ‘always seemed like walking into a novel’ a guest once commented in the 1880s, ‘such interesting people staying there and such interesting things going on’. Eglantyne’s Aunt Carrie agreed. ‘None of the places in novels are near the station, and no more was ours,’ she wrote on first visiting The Lyth. ‘We drove for a mile through the most beautiful country I have seen in England, full of lakes with distant hills, and then up a grand avenue of trees, until we came out on a lawn drive, and so to the front door.’ Little had changed when I arrived over a hundred years later. Eglantyne’s great nephew, Lionel Jebb, kindly met me at Oswestry station, dressed in his shooting outfit, dogs barking at his heels, and drove us all back the beautiful mile to Ellesmere and The Lyth. The house was built in the colonial villa style by a West Indian planter in the early 1800s and bought by Eglantyne’s paternal grandfather, a Salopian landowner, in 1838.1 A spacious two storeys, The Lyth’s luxurious dimensions are accentuated by long verandas front and back, and a stretch of tall windows opening to the ground that lead out to landscaped gardens. The verandas were ‘festooned by clematis and every rose then blowing’, Eglantyne’s eldest sister Em later wrote nostalgically about her childhood home, and ‘the green lawns … merge with sunk fences into park-like timbered field’. The clematis and rose were over when I arrived, but pots of geraniums, tiger lilies and tall agapanthus decorated the verandas, and immaculate lawns still led down to the park beyond where sheep were grazing in the late morning haze. It was an idyllic setting for an Edwardian childhood, that short moment when upper-class girls were free to roam house and gardens with their brothers but rarely allowed out to school.

‘Visitors round corner of verandah. Exodus of inhabitants.’ The Jebb children escape from The Lyth when dull visitors call, c.1895

As Lionel showed me round the house, half home, half fire-hazard, I began to feel like a fictional biographer in a post-modern satire. Assorted owls, hawks and herons observed our progress from glass cases, venerable ancestors peered down from gilt-frames, and a poster-sized photograph in the downstairs loo showed Lionel leaning dangerously into a hedge in 1830s costume, dressed for a party as the first Jebb to live at The Lyth. We eventually arrived, through lofty outer and inner halls, at the magnificent morning room where Lionel had stacked about twenty large boxes containing the family archive, or at least that part of it pertaining to Eglantyne. Here, surrounded by extraordinary hand-block-printed French wallpaper depicting rather frolicking scenes of ‘airily clad virgins and noble Romans in helmets’ – a design which would later reappear on the bedroom walls of one of Eglantyne’s fictional heroines – I set to work poring over great bundles of letters, diaries and journals, photographs and press-clippings.

Born in 1876, Eglantyne grew up in an active and intellectual household. As a child she created her special place among her five siblings as the family storyteller, otherwise joining in the general melee as they melted lead soldiers to make bullets, milked cows to make cheese, collected butterflies, flew kites, read Scott and rode horses. Drawings by the Jebb children showed them piling out of the dining-room on to the veranda when tedious visitors called, diaries and letters had them staging battles in the gardens and passing the hours on wet afternoons writing poems about illustrious and romantic ancestors. ‘You should see me,’ Eglantyne wrote to a friend, ‘sitting on a table on account of the mice, surrounded by a pile of books and all the ghosts clanking around.’

Eglantyne’s father, Arthur Jebb, whom she characterised as ‘a barrister, distressed landlord and father, Liberal-Unionist and grand old Tory’, and her mother, Tye, founder of the ‘Home Arts and Industries Association’, were Anglican Conservatives who instilled a strong social conscience and commitment to public service in their children. The son of a wealthy landowner and grandson of a Mayor of Oswestry, Oxford-educated Arthur was an influential member of the Shropshire gentry. But he was also a gentle and somewhat self-effacing intellectual; ‘sensitive as a woman’, his eldest daughter once commented.2 Arthur’s grandmother had been a pupil of the great portrait painter George Romney and his mother had inherited her artistic, poetic and deeply religious sensitivities. Although she died young his mother had a great influence on Arthur, who grew up with a love of literature and culture; interests that did not always sit easily with his position of country squire. As a young man Arthur found himself and his two sisters, Nony and Bun, the subjects of some gentle satire in the popular novel Gracechurch by John Ayscough.3 ‘Melancholy Launcelot’, as Arthur was monikered, ‘had been the old man’s pride, and was now his special irritation. He did not care much for radical politics – only just enough to prevent his being popular with the Tory squires around and their sons: nor was he horsey, or doggy.’ It was a sufficiently accurate picture to cause some mild local embarrassment, but Arthur accepted it gracefully enough for a copy of Gracechurch to find its way into the library at The Lyth.

Arthur’s strong sense of family connection to Shropshire, and to Wales where he also owned farms, stimulated a life-long interest in local history, place names and folklore, and his traditional ideas about social responsibility focused him on the livelihoods of his tenants and the welfare of the local community more widely. He was a sympathetic landlord who refused to raise rents in bad years, and often when he went rent collecting in Wales he would come back with plenty of game from his shoots, but rhymes of his own in place of the rents he was due. Given that ‘good hearts’ was a term for empty pockets, one such verse ran rather sweetly:

‘Silver and gold we are not rich in’

Said Mary dancing in the kit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Family Trees

- Illustrations

- Cast of Characters

- 1. Imagining Eglantyne, 2009–1876

- 2. Meeting the Family, 1876–1894

- 3. Unravelling Her Surroundings, 1895–1898

- 4. Testing the Maternal Impulse, 1898–1900

- 5. Happy Days, 1901–1902

- 6. Brief Studies in Social Questions, 1902–1910

- 7. Love Letters, 1907–1913

- 8. Relief in ‘The Barbarous Balkans’, 1913

- 9. Conversations with the Dead, 1914–1915

- 10. Surrounded by Action, 1914–1916

- 11. Found in Translation, 1917–1919

- 12. Save the Children, 1919

- 13. Hearts and Minds, 1919–1920

- 14. ‘Supranationalism’, 1920–1923

- 15. The Rights of the Child, 1922–1925

- 16. Blue Plaques, 1920–2009

- Epilogue: Truths and Lives

- The International Save the Children Alliance

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plates