- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Written by the world's leading experts and campaigners, Modern Slavery: A Beginner's Guide blends original research with shocking first-hand accounts from slaves themselves around the world to reveal the truth behind one of the worst humanitarian crises facing us today. Only a handful of slaves are reached and freed each year, but the authors offer hope for the future with a global blueprint that proposes to end slavery in our lifetime All royalties will go to Free the Slaves.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Perpetual chains: slavery throughout history and today

Wherever I go ... I’m a slave, chained in perpetual servitude. I may go to your deepest valley, to your highest mountain, I’m still a slave, and the bloodhound may chase me down.

Frederick Douglass, 1845

As the last phrases of the “Declaration of Independence” died away in Rochester’s Corinthian Hall on 5 July 1852, the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass rose to speak. He had insisted upon giving his Fourth of July speech, marking American independence, a day late, to remind his white audience that slavery was an anachronism – a rupture in American progress. While acknowledging the Declaration’s ideals of liberty and equality, he would protest the long delay in fully realizing them. Sure enough, his speech that day addressed the division between black and white, slave and free, in antebellum America. The nation, Douglass said, is “your nation,” its fathers are “your fathers.” Then he asked his audience: “What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July?” It is a cruel sham, he answered. A day of boasted liberties and empty rejoicing that renders slavery “more intolerable.”

Today, during bicentennial celebrations of the 1807 and 1808 acts that abolished the British and American external slave trades, Douglass’s question rings loud across the years. What, to the modern slave, is the bicentennial? What is the meaning of bicentennial celebrations when slavery still exists – 200 years after those acts, 175 years after the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, and more than 140 years after the American Emancipation Proclamation? And what was the historical journey that brought us to this point, with twenty-seven million people enslaved around the world? Just as Douglass set nineteenth-century slavery in its historical context, pointing to the Declaration of 1776, so we can trace a long pre-history for contemporary forms of slavery.

Slavery throughout history

Long before Douglass himself escaped slavery in 1838, slavery was part of our world. The practice is as old as human history and predates both laws and money. It was part of the Nile cultures from their earliest records; in the First Dynasty, around 7000 BC, slaves were sacrificed in the burials of nobles. Then, in ancient Mesopotamia, drawings in clay from 4000 BC show captives taken in battle by ancient Sumerians, tied, whipped, and forced to work. Sumer’s surviving records show a society ruled by a king claiming divine authority over a tightly organized city-state that rested on both serfs and slaves. The records point to wartime raids justified by religion as an important source of slaves.

Slavery continued to thrive in Babylon, a city-state in ancient Mesopotamia and the largest city in the world from 1770 to 1670 BC. Around 1790 BC, the Code of Hammurabi introduced the legal status of a slave. The Code laid out the first complete legal system and reveals the early inter-relationship of religion, law, and slavery in its prologue:

Bel, the lord of Heaven and earth, who decreed the fate of the land … called by name me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince … so that I should rule over the black-headed people like Shamash, and enlighten the land, to further the well-being of mankind. Hammurabi, the prince, am I … the shepherd of the oppressed and of the slaves.

In this earliest written code of laws the themes of divine approval, conquest, domestication (“shepherd … of the slaves”) and slavery are woven together.

The Code outlines a slave system in full operation. There are 282 separate laws regulating most of civil life, and thirty-five of them concern slavery. All are crystal clear: a slave is not a real human being. For example, one of these Babylonian codes explains that if a physician makes a fatal mistake on a patient, his hands are to be cut off – unless the patient is a slave, in which case the physician only has to replace the master’s property. Another mandates that if a man strikes a pregnant woman so that she loses her child, the man’s own daughter must be killed – unless the woman is a slave, in which case the offender need only pay her master two silver coins.

One of these ancient laws anticipates the United States’ infamous Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (which ordered that any person who helped a fugitive slave to avoid recapture was subject to a fine and imprisonment), instructing that anyone hiding a runaway slave “shall be put to death.” And Babylonian slavery shared another major characteristic with American chattel slavery: the free use of violence for control or punishment. The Code of Hammurabi notes that if “a slave strike a free man, his ear shall be cut off,” while the Louisiana Slave Code of 1724 explains that a “slave who will have struck his master … will be punished by death.”

In Egypt, the period known as the New Kingdom (1570–1070 BC) brought increased military expansion by the Pharaohs and a corresponding explosion of slavery. The most successful military leader of this period, Pharaoh Tutmose, campaigned every year into Syria and Palestine, and claimed to have enslaved more than 100,000 people. Paintings and carvings that survive from this period show ranks of bound captives, from the area that is now Israel and Palestine, and from further south in Africa. The Pharaoh used slave labor for large-scale public works projects, thereby reducing pressure on the peasants and farmers who worked in food production.

As the city-state structure emerged and spread, more societies became hierarchical, militaristic, and slaveholding. Control of farmland and animals was combined with the “domestication” and enslavement of human beings. At their pinnacle, the Greek city-states had large numbers of slaves. Around 400 BC, Athens and its companion port city of Pireaus contained around 60,000 citizens, 25,000 non-citizens, and 70,000 slaves. “With little exception,” notes one historian, “there was no activity, productive or unproductive, public or private, pleasant or unpleasant, which was not performed by slaves … in the Greek world.” Slaves were seen as essential for the perilous and often deadly work in silver mines that helped to fuel the growth of Athens. About the same time, the work of Plato was building a solid rationalization for slavery based on the inherent inferiority of “barbarians.” His pupil Aristotle enlarged this justification, arguing that slavery was good for both slave and master, since each were achieving their true function.

Rome’s economy was even more solidly based on slavery and the expansion of the Roman Empire led to a vast slave trade, mainly in captives from foreign conquest and their descendants. But over a period of about seventy years, from 135 BC to 70 BC, the Roman world was rocked by three large-scale slave revolts involving many thousands of slaves. The last of these uprisings, sometimes called the Gladiator War or the War of Spartacus, was initiated by a small band of enslaved gladiators and grew to an army of some 120,000 men that defeated the Roman army several times over a three-year period before being wiped out. Roman laws then became progressively more humane regarding the treatment of slaves in the first century AD. This change reflected an emerging philosophy that held slavery to be against “natural” law. Roman jurists, basing their ideas on the philosophy of the Stoics, suggested that while slavery was universally practiced it was also contrary to nature. With the contraction and fall of the Roman Empire, slavery diminished in proportion to the population held in serfdom.

Between 320 AD and 1453 AD, slavery was a large part of the Byzantine Empire’s economy. The expansion by force of the Empire flooded Constantinople with slaves. The emergence of agricultural surplus and ruling elites had established the three main supports of institutionalized slavery: an armed military that could use violence to enslave, a business market for slaves, and a religious elite that provided divine approval for slavery. One element of this approval involved the Judeo-Christian creation myth, namely the Curse of Ham. After the world is washed clean by a great flood, only the family of Noah survives to repopulate the world. Noah’s son Ham and his descendents are cursed to be the “servant of servants … unto his brethren,” and while the Biblical account makes no mention of skin color, a strong narrative emerged that named Africans as the descendents of Ham. A religious commentary written around 350 AD explains: “[Ham] became a slave, he and his lineage, namely the Egyptians, the Abyssinians, and the Indians.”

Slavery also appears in the Jewish Torah, which provides rules for how Jews should treat their slaves. Jews were not supposed to enslave Jews, and if a Jewish person was taken into slavery because of debt, the bondage was limited to six years. But non-Jews could be enslaved for life and their enslavement could be passed on to their children. Around 2100 years ago, however, some Jewish communities began to reject slavery. The Essenes were the first Jewish faith community to outlaw slavery, and the Therapeutae, a Jewish people living near Alexandria, were described by a contemporary in this way: “They do not have slaves to wait upon them as they consider that the ownership of servants is entirely against nature. For nature has borne all men to be free.” In fact, practitioners of Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Judaism, and Confucianism all began to build theologies that were radically different to the past and emphasized compassion and justice.

But the Crusades opened up new Eastern populations to European enslavement. Genoa, Venice, and Verdun became major slave markets, especially after plague decimated the European workforce in the thirteenth century. Slavery became central to the economy of Tuscany. The position of the Church throughout this period was to condemn sales of Christians and to prohibit the buying of any Christians by Jews, while accepting slavery as an institution. Islam promulgated similar rules, forbidding the enslavement of Muslims by Muslims. Then, as the expansion of the European empires into Africa and the Americas began in the fifteenth century, the Church continued its support of slavery in both policy and trade.

Slavery in the British Empire and the United States

Just as the Roman and Byzantine empires had grown on the backs of newly enslaved people, so the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade marked the beginning of a global Europe. From the 1400s onward, European ships brought captured Africans to Europe as slaves. With the conquest and colonization of the Americas, the trade expanded to include North and South America and became triangular. Ships traveled from Europe to Africa, traded goods for captured Africans, and shipped these African captives to the Americas. The slaves who survived the journey were sold to the colonists, primarily for agricultural work, and the ships were reloaded with tobacco, sugar, cotton, and rum to head back to Europe, where the process would begin again. By 1888, when the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade finally came to an end with the abolition of slavery in Brazil, between eleven and twenty-eight million people had been taken from Africa.

Many millions of slaves were brought to the North American colonies. Enslaved Africans made up one-fifth of the population of New Amsterdam in 1664, when it was handed over to the British and renamed New York, and by the time of the American Revolution in 1775, the states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York held, together, almost 40,000 slaves. And the slave trade did not cease with the American Revolution. Concepts of free religious thought that had emerged in the Protestant Reformation were central to the ideas of equal citizenship and personal freedom in the founding of the new republics of the late eighteenth century. Squaring these beliefs with the powerful economic institution of slavery proved impossible and the result was a series of confused compromises. The constitution of the new United States guaranteed freedom and equality to all citizens, but denied these benefits to slaves. It was a continuing paradox: the first global empires were based on the economic power of slavery yet spread the countervailing ideals of the Enlightenment. Their culmination in the American republic was a revolution for liberty that preserved a slave system.

But as the ideas of the Enlightenment spread, so did a redefinition of slavery. As early as 1769, Adam Ferguson, a Scottish professor of philosophy, argued that “no one is born a slave; because everyone is born with his original rights.” Religious bodies began to reject slavery. The first moral tracts against slavery published by Quakers appeared in the early 1700s, and by 1758, Quakers in the American colonies and in Britain had condemned both the slave trade and slaveholding. In 1767 Quaker activists brought a proposed law against slavery into the Massachusetts legislature. The bill failed but the potential for the codification of a human right to freedom was established. Persistent activism by Quakers included the organization of “little associations” against slavery in the American colonies, which laid the groundwork for the debates over slavery that followed the American Revolution.

Then, in 1787, a handful of Quakers and a young Anglican, Thomas Clarkson, formed the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade (re-named the Anti-Slavery Society in 1823). Based in London, it was the world’s first human rights organization. Its goal was the complete abolition of the slave trade and the emancipation of the slaves throughout the Empire. Although England itself had few slaves – unlike the Caribbean and the North American colonies – English capitalists were deeply involved in the trade.

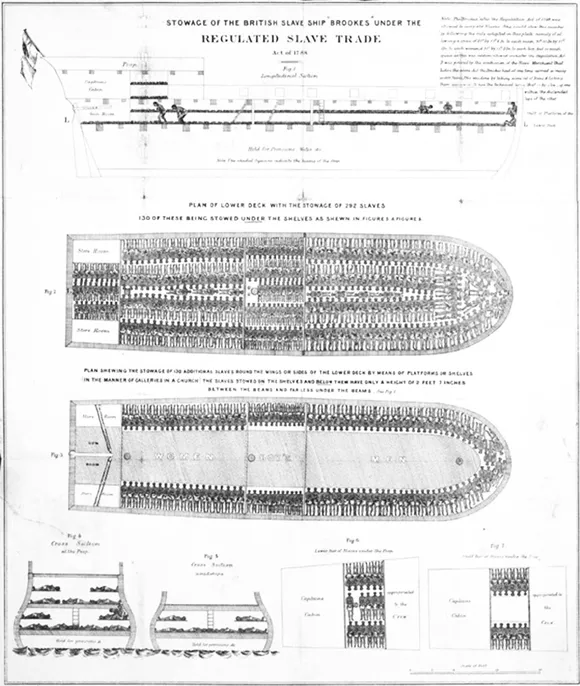

By 1791 the Committee had 1300 local branches across Great Britain. The campaign boycotted products produced by slavery, such as sugar from colonies in the Caribbean, raised public awareness, circulated petitions, and lobbied the government to outlaw the slave trade. One lobbyist was the former slave Olaudah Equiano, who published his autobiography in 1789. Here he protested the conditions of the middle passage, explaining that the “closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship … almost suffocated us.” Other abolitionists confirmed the realities of Equiano’s description by using technical diagrams of this “place” within their print culture. After an abolitionist group in Plymouth produced a diagram of a slave ship, Clarkson and other abolitionists modified it to show the ship loaded with 482 slaves. In 1789, they printed and circulated 7000 posters of the image, which quickly became iconic (see figure 1).

In 1807, the British slave trade was legally abolished. After the end of the Napoleonic wars, the anti-slavery campaign began again, this time aimed at abolishing the institution of slavery itself. Legal slavery in the British Empire ended in 1833. But as one abolitionist movement came to an end, another was just getting started. In the United States, slave importation was legally (if not functionally) ended in 1808, but the US South continued to maintain and grow its slave population by natural increase. Linked to the plantation system and an explosive growth in demand for cotton, the slave population in the southern states of North American grew to about four million by 1860. And as slavery grew in the southern states, so too did American slave resistance.

In 1791, the former Haitian slave Toussaint L’Ouverture had transformed a slave revolt into a revolution, the abolition of slavery, and – eventually – the proclamation of the Haitian Republic in 1804. The success of the Haitian revolution instilled fear into the slaveholders of the southern US and this fear was well founded. By the time of the Civil War, more than 250 small-scale slave revolts had occurred in the South. The most significant of these was Nat Turner’s revolt of 1831 in Virginia. Turner led seventy other slaves in a rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia, and the rampage left dead sixty whites and one hundred blacks. It remains the most famous slave revolt in American history.

Beyond this violent slave resistance in the US South itself, Africans also mutinied on slave ships 392 times by 1860 – on as many as ten percent of slave-ship voyages. Most famous were the Amistad and Creole revolts of 1839 and 1841. In late June 1839, captive West Africans rebelled and seized control of the Spanish slave-ship Amistad, which was traveling along the coast of Cuba. The rebel leader was Sengbe Pieh (popularly known as Joseph Cinque) and he ordered the surviving crew members to sail the ship, with its fifty-three slaves, to Africa. But for two months the crew moved the ship back west at night, until it was sighted and seized by the US Navy off the coast of Long Island in late August. The Africans were charged with murder and abolitionists took up their cause. They were declared legally free by a federal trial court in 1840 and by the Supreme Court in 1841. By 1842 they had returned to Africa.

Figure 1 Stowage of the British slave ship Brookes

Around the same time, in 1841, Madison Washington led a slave revolt onboard the US brig Creole and brought into sharp relief the now divergent paths of Britain and America around the question of slavery. The ship left the port of Richmond, Virginia on 25 October 1841, with 135 slaves. It was bound for New Orleans, Louisiana, where the slaves would be sold at auction. As it neared Abaco Island in the Bahamas, Washington and eighteen other slaves seized pistols and knives, subdued the crew, and sailed for British-controlled Nassau, a port in the Bahamas. The British Emancipation ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Illustrations

- 1. Perpetual chains: slavery throughout history and today

- 2. By yet another name: definitions and forms of modern slavery

- 3. A money-making system: modern slavery and the global economy

- 4. Their own sufferings: modern slavery for women and girls

- 5. Of one blood: racial, ethnic, and religious aspects of modern slavery

- 6. Subjugated soldiers, terrorized terrain: armed conflict and environmental destruction as factors in modern slavery

- 7. The suffering of multitudes: modern slavery’s health risks and consequences

- 8. To effect its abolition: ending slavery in our lifetimes

- Notes

- Further reading

- Glossary

- Appendix A: timeline

- Appendix B: anti-slavery legislation

- Appendix C: anti-slavery organizations

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Modern Slavery by Kevin Bales, Zoe Trodd, Alex Kent Williamson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Slavery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.