- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

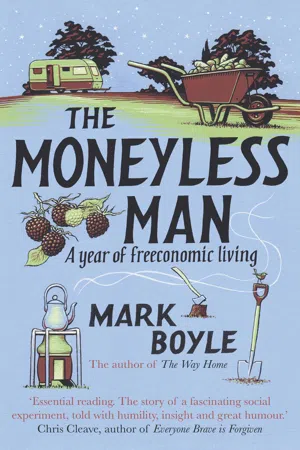

About this book

The astonishing reality of living without our most important resource: money.

'An inspiring and entertaining guide to escaping the money trap and reconnecting with reality.' Paul Kingsnorth, author of Real England

Imagine a year living without spending money...

Former businessman Mark Boyle undertook this extraordinary challenge and recounts the amazing adventure it led him on. Going back to basics and following his own strict rules, Mark learned ingenious ways to eliminate his bills and discovered that friendship has no price.

Encountering seasonal foods, solar panels, skill-swapping schemes, caravans, compost toilets, and – the unthinkable – a cash-free Christmas, Boyle puts the fun into frugality and offers some great tips for economical (and environmentally friendly) living. A testament to Mark’s astounding determination, this witty and thought-provoking book will make you reevaluate what is most precious in life.

'An inspiring and entertaining guide to escaping the money trap and reconnecting with reality.' Paul Kingsnorth, author of Real England

Imagine a year living without spending money...

Former businessman Mark Boyle undertook this extraordinary challenge and recounts the amazing adventure it led him on. Going back to basics and following his own strict rules, Mark learned ingenious ways to eliminate his bills and discovered that friendship has no price.

Encountering seasonal foods, solar panels, skill-swapping schemes, caravans, compost toilets, and – the unthinkable – a cash-free Christmas, Boyle puts the fun into frugality and offers some great tips for economical (and environmentally friendly) living. A testament to Mark’s astounding determination, this witty and thought-provoking book will make you reevaluate what is most precious in life.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Personal DevelopmentSubtopic

Social Science Biographies1

WHY MONEYLESS?

Money is a bit like love. We spend our entire lives chasing it, yet few of us understand what it actually is. It started out, in many respects, as a fantastic idea.

Once upon a time, people used barter, instead of money, to look after many of their transactions. On market day, people walked around with whatever they had produced; the bakers took their bread, the potters brought their earthenware, the brewers dragged their barrels of ale and the carpenters carried wooden spoons and chairs. They negotiated with the people they hoped would have something of value to them. This was a really great way for people to get together but it wasn’t as efficient as it could have been.

If Mr Baker wanted some ale, he went to see Mrs Brewer. After a chat about the kids, Mr Baker would offer some bread in return for some of Mrs Brewer’s delicious ale. A lot of the time, this would be perfectly acceptable and both parties would come to a happy agreement. But – and here is where the problem began – sometimes Mrs Brewer didn’t want bread or didn’t think her neighbour was offering enough in exchange for her beer. Yet Mr Baker had nothing else to offer her. This problem has become known as ‘the double coincidence of wants’: each person in a transaction has to have something the other person wants. Perhaps Mrs Brewer had discovered her husband was glutenintolerant and so Mr Baker had been contributing to her lesser half’s irritable bowel syndrome. Or that rather than bread, she really wanted a new spoon from Mrs Carpenter and some fresh produce from Mrs Farmer. This was all very confusing for poor Mrs Brewer.

One day, a man in an exquisite top hat and tailor-made pinstriped suit entered the small town. The people had never seen him before. This new chap – he introduced himself as Mr Banks – went to the market and laughed as he watched the hustle and bustle as everyone chaotically mingled and tried to get what they needed for the week. Seeing Mrs Farmer unsuccessfully trying to swap her vegetables for some apples, Mr Banks pulled her aside and told her to get all the townspeople together that evening in the Town Hall, as he knew a way in which he could make their lives so much easier.

That evening, the entire community came, jostling with excitement and intrigued to know what this charismatic stranger in the top hat and beautiful suit was going to say. Mr Banks showed them ten thousand cowry shells, each stamped with his own signature, and gave one hundred shells to each of the one hundred townspeople. He told them that, instead of carrying around awkward beer barrels, loaves, pots and stools, the people could use these shells to trade for their goods. All everyone would have to do was decide how many shells their wares and produce were worth and use the little tokens to do the exchanging. ‘This makes a lot of sense’, said the people, ‘our problems have been solved!’

Mr Banks said he would return in a year and that when he did, he wanted the people to bring him one hundred and ten shells each. The ten extra shells, he said, would be a token of their appreciation for how much time he had saved them and how much easier he had made their lives. ‘That sounds fair enough but where will the ten extra shells come from?’ said the very smart Mrs Cook, as he climbed off the stage. She knew that the villagers couldn’t possibly all give back ten extra shells. ‘Don’t worry, you’ll figure it out eventually’, said Mr Banks as he walked off to the next town.

And that, by way of simple allegory, was how money came into being. What it has evolved into is far removed from such humble beginnings. The financial system has become so complicated that it almost defies explanation. Money isn’t just the notes and coins we carry in our pockets; the numbers in our bank accounts are only the start. There are futures and derivatives, government, corporate and municipal bonds, central bank reserves and the mortgage-backed securities that so famously caused the world-wide collapse of financial institutions in the 2008 credit crunch. There are so many instruments, indices and markets that even the world’s experts can’t fully understand how they interact.

Money no longer works for us. We work for it. Money has taken over the world. As a society, we worship and venerate a commodity that has no intrinsic value, to the expense of all else. What’s more, our entire notion of money is built on a system which promotes inequality, environmental destruction and disrespect for humanity.

DEGREES OF SEPARATION

By 2007, I had been involved in business in some way for nearly ten years. I had studied business and economics in Ireland for four years, followed by six years managing organic food companies in the UK. I had got into organic food after reading a book about Mahatma Gandhi during the final semester of my degree. The way this man lived his life convinced me that I wanted to attempt to put whatever knowledge and skills I had to some positive social use, instead of going into the corporate world to make as much money as I could as quickly as possible, which was my original plan. One of Gandhi’s sayings, which struck a chord with me, was ‘be the change you want to see in the world’, whether you are a ‘minority of one or a majority of millions’. The trouble was, I had absolutely no idea what that change was. Organic food seemed (and in many respects still does) to be an ethical industry, so that looked a good place to start.

After six years deeply involved in the organic food industry, I began to see it as an excellent stepping-stone to more ecologically-sound living, rather than the Holy Grail of sustainability I had once believed it. It had many of the problems rife in the conventional food industry: food flown across the world, convenience goods packed in too many layers of plastic and large corporations buying up small independent businesses. I became disillusioned and began exploring other ways to join the growing movement of people world-wide who were concerned about issues such as climate change and resource depletion and wanted to do something about them.

One evening, chatting with my good friend Dawn, we discussed some of the major issues in the world: sweatshops, environmental destruction, factory farms, resource wars and the like. We wondered which we should dedicate our lives to tackling. Not that either of us felt we could make much difference; we were just two small fish in a hugely polluted ocean. That evening, I realised that these symptoms of global malaise were not as unrelated as I had previously thought and that the common thread of a major cause ran through them: our disconnection from what we consume. If we all had to grow our own food, we wouldn’t waste a third of it (as we do now in the UK). If we had to make our own tables and chairs, we wouldn’t throw them out the moment we changed the interior décor. If we could see the look on the face of the child who, under the eyes of an armed soldier, cuts the cloth for the garment we contemplate buying on the high street, we’d probably give it a miss. If we could see the conditions in which a pig is slaughtered, it would put most of us off our bacon butty. If we had to clean our own drinking water, we sure as hell wouldn’t shit in it.

Humans are not fundamentally destructive; I know of very few people who want to cause suffering. But most of us don’t have the faintest idea that our daily shopping habits are so destructive. Trouble is, most of us will never see these horrific processes or know the people who produce our goods, let alone have to produce them ourselves. We see some evidence through news media or on the world-wide web but these have little effect; their impact is seriously reduced by the emotional filters of a fibre-optic cable.

Coming to this conclusion, I wanted to find out what enabled this extreme disconnection from what we consume. The answer was, in the end, quite simple. The moment the tool called ‘money’ came into existence, everything changed. It seemed like a great idea at its conception, and 99.9% of the world’s population still believe it is. The problem is what money has become and what it has enabled us to do. It enables us to be completely disconnected from what we consume and from the people who make the products we use. The degrees of separation between the consumer and the consumed have increased massively since the rise of money and, through the complexity of today’s financial systems, are greater than ever. Marketing campaigns are specifically designed to hide this reality from us; and with billions of dollars behind them, they’re very successful at it.

MONEY AS DEBT

In our modern financial system, most money is created as debt by private banks. Imagine there is only one bank. Mr Smith, who up to now has kept his money under the bed, decides to deposit his life savings, 100 shells, in this bank. Naturally, the bank wants to make a profit, so decides to lend out a proportion of Mr Smith’s shells, let’s say 90 of them, keeping ten in their coffers in case Mr Smith wants to make a small withdrawal. Another gentleman, Mr Jones, needs a loan. He goes to the bank and is delighted to be given Mr Smith’s 90 shells, which he’ll eventually have to pay back with interest. Mr Jones takes the shells and elects to spend them on bread, bought from Mrs Baker. At the close of the day, Mrs Baker takes her newly-acquired 90 shells to the bank. Do you see what’s happened? Originally, Mr Smith deposited 100 shells in the bank. Now, in addition to Mr Smith’s 100 shells, the bank has Mrs Baker’s 90 shells. One hundred shells has become 190. Money has been created. What’s more, the bank can now lend out a proportion of Mrs Baker’s deposit! The process can start again.

Of course, the physical number of shells hasn’t changed. If both Mr Smith and Mrs Brown wanted their shells back at the same time, the bank would be in a fix. However, this rarely happens and if it did, the bank would have shells from other depositors to use. The problems start when the bank lends out 90% of all their depositors’ shells. The result is that of all the shells in all the bank accounts of this fictional world, only 10% exist! If all the depositors wanted more than 10% of the total amount of shells at the same time, the bank would collapse (a bank run) and people would realise that the bank was creating imaginary money.

This system may seem ridiculous but it is what happens today, every day, in every country of the world. Instead of one bank, there are thousands. Instead of shells, we have the world’s myriad currencies. But the principle is the same: most money is created by private banks’ lending. Our most precious commodity doesn’t represent anything of value and the figures in your bank account are mostly someone else’s debt, which itself is funded indirectly by another person’s debt and so on. Neither are bank runs fictional. Recent bank crises, from Northern Rock in the UK to Fannie Mae in the US, show the inherent instability that comes from basing our financial system on an imaginary resource. The edifice is built on pretence and, as shown by 2009’s bank bail-outs across the world, tax-payers inevitably have to subsidise with billions to keep the pretence alive when the system implodes.

DEBT FORCING COMPETITION, NOT CO-OPERATION

In the current financial system, if deposits stay in banks, the banks make no interest and therefore no money. Therefore, banks have a huge incentive to find borrowers by whatever means possible. Whether by advertising, offering artificially low interest rates or encouraging rampant consumerism, banks share an interest in lending out almost all of their deposits. The credit this creates is, in my opinion, responsible for much of the environmental destruction of the planet, as it allows us to live well beyond our means. Every time a bank issues a human with a credit note, the Earth and its future generations receive a corresponding debit note.

It seems we can’t get enough of it. According to a Credit Action report published in 2010, there are now 70 million credit cards in the UK; the UK has more ‘flexible friends’ than people. The average household debt (excluding mortgages) is over £18,000 and to compound the situation, at the time of writing the UK’s national debt is growing by an astonishing £4,385 every second. Payback time, in both economic and ecological terms, will inevitably come. Whilst all this money creation is great for the economy, it is not so good for the people that the economy was originally intended to serve. Every day, the UK charity Citizens’Advice helps more than 9,300 people who need professional support to deal with their debts, one person is declared bankrupt or insolvent every four minutes and a house is repossessed every eleven and a half minutes.

In the end, the process of money creation inevitably means the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. Banks lend out money that, by any objective measure, they didn’t have in the first place and at every stage, accrue interest and keep the right to repossess real assets if loans are not repaid. Is there any wonder that huge inequality exists in the world?

Let’s return to our little town. In the past, at times such as harvest, it was common practice for the people to often help each other out on an informal, non-exchange basis and the people there co-operated a lot more than they do today. This cooperation provided them with their primary sense of security; indeed, a culture of collaboration still exists in parts of the world where money is deemed less important. However, the pursuit of money and humans’ insatiable desire for it has encouraged us to compete against each other in a bid to get ever more. In our little town, competition replaced the co-operation that once prevailed. Nobody helped their neighbours bring in the harvest for free any more. This new competitive spirit was partly responsible for many of the town’s problems, from feelings of isolation to a rise in suicide, mental illness and anti-social behaviour. It has also contributed to environmental problems, such as the depletion of resources and the climate chaos that currently go hand-in-hand with relentless economic growth.

MONEY REPLACING COMMUNITY AS SECURITY

For most of us, money represents security. As long as we have money in the bank, we’ll be safe. This is a precarious position to adopt, as countries such as Argentina and Indonesia, which have recently suffered hyper-inflation, will attest. The boom period the world experienced at the start of the twenty-first century – a bubble inflated by highly-pressurised bank executives – has been punctured. Many politicians, economists and analysts are still not sure if there was only one thorn.

Whilst I’ve no doubt that we’ll make it through this downturn and maybe even a few more, future economic crises will not be so easy to manipulate and stimulating recovery will be harder, as these challenges will be affected by real-world problems. The banking industry is inherently unstable and two of the pillars of our economy, the insurance and oil industries, will eventually take a huge hit from two massive and evolving problems: climate change and ‘peak oil’.

CLIMATE CHANGE

Whatever your beliefs about why the climate is changing, it’s undeniable that it is. It’s also certain that the damage it will cause is going to cost someone an incredible amount of money. In 2006, Rolf Tolle, a senior executive of Lloyd’s of London, warned that insurance companies could become extinct unless they seriously addressed the threats climate change poses to their business. Ultimately, there are two scenarios: either the insurance companies continue to cover ‘acts of God’ (or, more accurately, ‘acts of humanity’) and drastically increase our premiums to protect themselves – yet still risk extinction; or they stop covering them and the people whose homes and possessions are wiped out pick up the tab, ruining local economies and creating one humanitarian crisis after another.

PEAK OIL

‘Peak oil’ – a huge subject – boils down to one simple fact: our entire civilisation is based on oil. If you don’t believe me, take a look around wherever you are now and try to find one thing that either isn’t made from oil (remember plastics are oil-based) or wasn’t transported using it. Oil is a finite resource: when it will run out is up for discussion but the fact that it will run out is not. What’s more, even before the wells run dry, speculation will push up prices, so that oil will increasingly become unaffordable for more and more people. According to Rob Hopkins, founder of the Transition Network, we are using four barrels of oil for every one we discover, meaning that we are already moving rapidly towards this scenario. To highlight how critical oil is in our lives, Hopkins adds that the oil we use today is the equivalent of having 22 billion slaves hard at work – or each person on the planet having just over three. Oil is the sole reason that we in the West can live the lives we do; lives which are unsustainable in every sense of the word.

Governments may be able to bail out banks during times such as the 2008 credit crunch; unfortunately, we are also approaching what George Monbiot calls the ‘Nature Crunch’. As he correctly points out, nature doesn’t do bail-outs. Pavan Sukhdev, a Deutsche Bank economist who led a study of ecosystems, reported that we are ‘losing natural capital worth somewhere between $2 trillion and $5 trillion every year as a result of deforestation alone’. The credit-crunch losses incurred by the financial sector amount to between $1 trillion and $1.5 trillion; these pale in comparison to the total amount we lose in natural capital every year. As we lurch towards environmental disaster and the economy contracts, will money continue to be seen as security? Or will living in a closelyknit community that has re-learned its ability to work together and share for the common good take its place?

This became apparent to me when I went back to Ireland, to visit my parents, in 2008. In the six years I’d been away from my homeland, working in the UK, the country had changed beyond recognition. The growth that Irish people experienced during the ‘Celtic Tiger’ economic period had radically affected their culture. Twenty years earlier, when I was growing up at the end of the eighties, it had seemed very different. My memories were symbolised by the street where my parents still live. When I lived there, everyone knew each other; it could take fifteen minutes to get ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 Why moneyless?

- 2 The rules of engagement

- 3 Preparing the foundations

- 4 Buy Nothing Eve

- 5 The first day

- 6 The moneyless routine

- 7 A risky strategy

- 8 Christmas without money

- 9 The hungry gap

- 10 A spring in my step

- 11 Unwelcome visitors and distant comrades

- 12 Summer

- 13 The calm before the storm

- 14 The end?

- 15 Lessons from a moneyless year

- Epilogue

- Useful websites

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Moneyless Man by Mark Boyle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.