- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The universe is literally made of light

One hundred years after they were written, Marie Curie’s notebooks are still too radioactive to handle

In 1974 we sent a message to star cluster M13. If any aliens respond promptly, we’ll hear from them in 52000

From world-altering discoveries of the past to the wonderful science of the present, Bob Berman zooms across the universe to tell the story of invisible light. He reveals what microwaves from smartphones do to our brains, how birds use ultraviolet light to track prey, why gamma rays are the most powerful form of light, and so much more. Replete with amazing characters and mindboggling quantum leaps, Zapped offers a teasing peek into the future and some of the startling technologies we might yet live to see.

One hundred years after they were written, Marie Curie’s notebooks are still too radioactive to handle

In 1974 we sent a message to star cluster M13. If any aliens respond promptly, we’ll hear from them in 52000

From world-altering discoveries of the past to the wonderful science of the present, Bob Berman zooms across the universe to tell the story of invisible light. He reveals what microwaves from smartphones do to our brains, how birds use ultraviolet light to track prey, why gamma rays are the most powerful form of light, and so much more. Replete with amazing characters and mindboggling quantum leaps, Zapped offers a teasing peek into the future and some of the startling technologies we might yet live to see.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Zapped by Bob Berman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Optics & Light. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Optics & LightCHAPTER 1

Light Fantastic

If God really did say, “Let there be light,” it was no small housewarming present. There is a lot of light in the universe — one billion photons of light for every subatomic particle. In terms of individual items in the cosmos, including the components of atoms, photons constitute 99.9999999 percent of everything. The universe is literally made of light. And that includes not only ordinary everyday visible light but also the vast majority of light — the kind we cannot see.

Light is an astonishing entity, and the quest to understand it has obsessed the greatest thinkers in disparate cultures through the centuries. The ancient Greeks, probably by sheer dumb luck, were the first to hit upon a key aspect of visible light — that it does not exist independent of us as observers. Physics now tells us that light is made up of intertwined magnetic and electrical fields. Since neither magnetism nor electricity is visible to our eyes, light is inherently invisible.

When we look at a bright orange sunset, we’re not directly perceiving actual light. Rather, the energy reaching us from those electromagnetic pulses stimulates billions of neurons in our retinas and brains, which then fire to arouse a complex neurological architecture that produces in us the sensation of orange. An entire biological empire is thus as essential to the existence of brightness and colors as the photons themselves.

The Greeks didn’t know anything about brain structure, of course, yet they still figured out that light is a sensation, with no existence independent of the observer — which was either amazingly perceptive or just a lucky guess. But the Greeks had light’s direction wrong. Knowing that its speed appeared instantaneous, they didn’t imagine that a pulse of light originating in a candle sped in our direction until it struck our eyes. On the contrary, they regarded light as a ray traveling outward from our pupils. This belief, that our eyes project an illuminating beam, was universally embraced for more than a millennium. Even so, a few early iconoclasts envisioned eyesight as an interplay between this supposed eye ray and something emitted by other sources.

The classical thinker who came closest to the truth about light was the Roman Lucretius, who in the first century BCE, in his On the Nature of Things, wrote, “The light and heat of the sun are composed of minute atoms which, when they are shoved off, lose no time in shooting right across the interspace of air.”

Lucretius’s view of light as particles — later supported by Isaac Newton — included that profound “lose no time” characterization, showing that he believed light moved immeasurably fast. But whether scientists considered its speed merely super-quick or instantaneous, light remained popularly regarded as a phenomenon that originates in the eye for centuries to come.

The first true breakthrough came from the mathematician and astronomer Alhazen — formally known as Abu Ali al-Hasan ibn al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham — who lived in Egypt during the golden age of Arab science. Around the year 1020, when the rest of the world was in the intellectual coma of the Dark Ages, Alhazen said that vision results solely from light entering the eye; nothing emanates from the eye itself. His popular pinhole camera obscura, which drew astonished yelps of wonder when visitors observed the phenomenon, gave weight to his arguments, for here was a full-color “motion picture” of nature splayed out on the walls. But Alhazen went much further. Light, he said, consists of streams of tiny, straight-moving particles that come from the sun and are then reflected by various objects. Sounds simple, perhaps, but Alhazen’s spot-on conclusions were six centuries ahead of anyone else’s.

The Renaissance turned up the juice on the “What is light?” debate, which eventually took on the quality of a food fight. In the late seventeenth century, Newton joined astronomer Johannes Kepler in arguing that light is a stream of particles, while men such as Robert Hooke, Christiaan Huygens, and, soon, Leonhard Euler insisted that light is a wave. But what is it a wave of? They thought there had to be a substance doing the waving, so these Renaissance scientists decided that space was filled with a plenum (later called an ether), an invisible substance that facilitated the movement of magnetic and electrical energy.

One obvious fact managed to sway many in favor of Newton’s particle idea. When light from the sun passes a sharp edge, such as the wall of a house, it casts a sharp-edged shadow on nearby objects. That’s what particles moving in a straight line should do. If instead light were made of waves, it ought to spread out — diffract — as ocean waves do when passing a jetty. To the particle proponents, the existence of sharp-edged shadows, combined with Newton’s reputation as a genius, made the wave proponents seem like nut jobs.

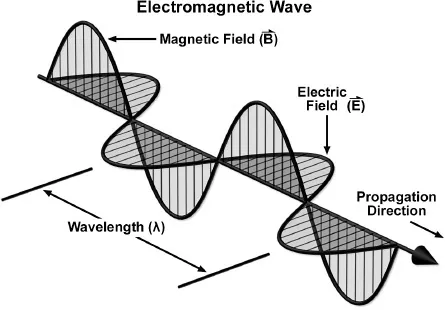

The particles-versus-waves controversy eventually took a curious turn. As if some wise King Solomon ruled nature, everyone was soon declared right. The biggest breakthrough came from Scottish physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell, who in 1865 showed that all light is a self-sustaining wave of magnetism with an electric pulse wiggling at right angles to it. One type of pulse stimulates the other, so that both the electrical and the magnetic waves continue indefinitely. From then on, science called light an electromagnetic phenomenon.

All light consists of a dual wave. A magnetic pulse is accompanied by an electric pulse positioned at a ninety-degree angle to it. (Molecular Expressions at Florida State University)

But where did this phenomenon come from? In 1896, the Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz figured out that the existence of a strange phenomenon — light splitting itself in two within a strong magnetic field — must mean that the rapid motion of some tiny, unknown, negatively charged particle has to be the source of all light everywhere in the universe. A year after he drew this astoundingly prescient conclusion, the first subatomic particle was discovered. This was the electron, whose movements are indeed the sole creator of all light. For predicting the existence of the electron before its actual discovery, Lorentz won the Nobel Prize in 1902.

How exactly is light — any light, all light — created? When an atom gets struck by energy — from a quick zap of electricity or a collision with a stray electron or the introduction of heat — its wiggling motion is jolted into a greater speed. This extra energy excites the atom’s electrons, which give a figurative yelp and jump to an orbit farther from the nucleus. They don’t like to be there, so in a fraction of a second they fall back into a closer, smaller orbit. As they do so, the atom surrenders a bit of energy. Since energy is never lost under any circumstances, this energy must manifest itself in some other way. And it does. A bit of light, a photon, materializes out of the emptiness as if by magic — then instantly rushes away at its famous breakneck speed. That’s the only way light is ever born. Out of seeming nothingness, whenever an electron moves closer to its atom’s center. Simple, really.

So light can be thought of as a set of two waves, one of electricity and one of magnetism, or as a weightless particle called a photon. Taking our cue from Albert Einstein, we might visualize a photon as a tiny bullet, an energetic speck with no mass, weighing nothing and with the curious property of being unable to ever stop moving. Nowadays, most people who think about such things (we science nerds) find it easiest to visualize light as a wave when it’s en route from point A to point B and as a photon when it finishes its journey by crashing into something. But one may call light a photon or a wave and be equally correct.

The twentieth century brought us quantum theory, which — in addition to showing that solid objects such as electrons can behave as energy waves, too — revealed something extremely weird: when an observer uses an experimental apparatus to determine the location of photons or subatomic particles such as electrons, these entities always behave as particles and do things only particles can do, such as pass through one little hole or another but not both at once. But when no one’s measuring where exactly each photon is situated, they behave as waves that blurrily pass through both holes in a barrier simultaneously to create an interference pattern on a detector located beyond the openings — which only waves can do.

Thus the observer and, weirdly, the information in his or her mind plays a critical role in whether light exists as a wave or as a tiny discrete object. The same is true for particles of matter. What you see depends on how you observe and what you know. Most physicists now think that a human consciousness is required to make a photon or an electron’s “wave function” collapse so that it occupies a particular place as a particle. Otherwise it’s just a theoretical object with neither location nor motion.

Just a century ago, the local realism mind-set of science, and even common sense, held that all objects, including atoms and photons, have an existence independent of our observation of them. But that’s been replaced by a more modern view — that our observation itself is necessary for the very existence of photons and electrons, a spooky prospect.

But does an electron’s wave function collapse and turn into an actual particle if a cat is watching? Would light always be waves and never discrete photons if no humans were around? Our best answers are “Who knows?” and “Yes” respectively, but obviously this whole business is Wonderland-strange.*

Let’s make this strangeness clearer. A century ago, if we detected a bit of light (or even a physical particle) arriving at an instrument with which we could measure its incoming direction, we’d have confidently plotted out its previous path. No longer. Now we say that it had no path before we started to observe it. It possessed no real existence as an actual photon or electron or whatever it was. Rather, its observed existence is its only existence. Observation establishes reality. Nothing else is certain. As the late physicist John Wheeler put it, “No phenomenon is a real phenomenon until it’s an observed phenomenon.”

Which brings us to our next question: why can we observe some kinds of light with the naked eye and not others?

* My friend Matt Francis, an electron microscopist, is training his dog to recognize and respond to light displayed as a wave pattern on a screen as opposed to a series of particles. If he succeeds in teaching the dog to bark when observing waves and remain silent when observing only particles, he may be able to settle the matter and determine whether a dog’s consciousness can “collapse” a photon into its particle configuration. Yes, such issues actually obsess some of us.

CHAPTER 2

Now You See It, Now You Don’t

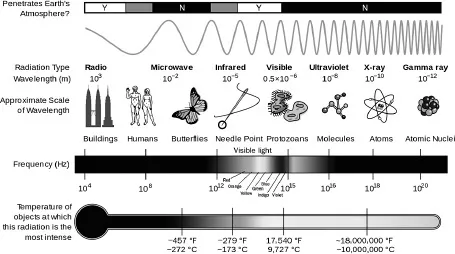

All forms of light, from the visible to the invisible, reside on the electromagnetic spectrum. Along this range there are many kinds (and colors) of light, and each variety can be distinguished from the others by two straightforward properties.

The first is wavelength. The length of each individual light wave varies from the tiniest fraction of an inch to more than a mile and spans everything in between.

The second is frequency, meaning the period of time it takes the wave to pass you and be replaced by the next wave, as if you were seated in a reviewing stand watching the light parade before your eyes.

Think of an ocean wave. In the open sea, a typical wave is around one hundred yards, or ninety-one meters, long — roughly the length of a football field. Its frequency is a bit less than one second. This means that each wave’s peak requires nearly a second to pass any given point and be replaced by a trough, which in turn is followed by the peak of the next wave.

Science can identify any wave, or any particular type of light, by either its length or its frequency. For example, each wave of green light at a traffic signal has a length of 530 nm (or nanometers, meaning 530 billionths of a meter), which is about one millionth of an inch. These tiny waves have a frequency of 530 THz, or terahertz, which means that 530 trillion of them pass your eye each second. (That the number 530 appears in both wavelength and frequency is a coincidence; the matchup is true of green light but not of any other color).

When the signal turns red, you perceive waves of a longer length — twice as long, in fact. Each crimson-light wave is around two millionths of an inch from crest to crest. Red light has the longest waves of all visible light, but they’re still smaller than most germs in our body. These waves vibrate more slowly than green light, too, with “just” 450 trillion wave pulses occurring per second. What’s important is that all the light we see has wavelengths somewhere between 400 and 700 nm, which used to be expressed as 4, 000–7,000 angstroms. The light we cannot see has wavelengths either shorter or longer than that.

Short waves pulse, or change, more quickly than long ones, and this gives them more power, or energy. As a result, while the light we can see is too weak to break atoms apart, fast-vibrating light such as ultraviolet light can indeed strip an atom of one or more of its electrons, which alters molecules and can lead to consequences such as carcinogenesis.

Invisible light has generally been named according to either its wave size or its position on the spectrum compared to the visible colors. Thus infrared light occupies a place just before the visible red light in the spectrum, meaning its waves are a bit longer than the red-light waves coming at you when you’re stopped at a traffic light. By contrast, ultraviolet light lies just after violet light, and its waves are slightly shorter.

The weakest kind of light is a radio wave. The longest radio waves measure a thousand miles from crest to crest. By contrast, the distance from one visible light wave to the next is just one millionth of a meter, or one hundred-thousandth of an inch. A few hundred trillion visible waves pass you every second. Even more mind-bogglingly short and fast are gamma rays, the strongest kind of light, with crests spaced just a trillionth of a meter apart and frequencies of a billion trillion per second. All other parts of the spectrum lie in between radio waves and gamma rays.

Visible light occupies only a tiny part of the electromagnetic spectrum. (Wikimedia Commons)

Except for the dim glow of the stars, all light is ultimately solar. Moonlight is reflected sunlight. The aurora borealis results from solar particles electrically stimulating the sparse oxygen atoms a hundred miles up. Candlelight and other kinds of flame require combustible materials such as coal, wood, and oil, which are forms of stored energy from long-dead plants and animals that would never have existed without the sun.

In our era we also create light using electricity, but that, too, comes from burning oil, gas, coal, or hydropower generated by falling water, which would never circulate back to higher altitudes without everyday solar warmth. Only nuclear power and starlight are independent of the sun, and stars emit exactly the same visible and invisible rays as our own sun does. Stars differ only in their proportions: hot, massive stars emit copious ultraviolet rays and blue light, whereas the more numerous lightweight stars give off copious reds, oranges, and infrared radiation, with very few UV rays. Rather poetically, our eyes see only the colors the sun emits most strongly. Our retinas are designed to perceive sunlight’s most abundant energies and nothing else. So we really do have a sun bias. In a way, we scan the universe through the sun’s eyes.

As we learned in science cla...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1: Light Fantastic

- CHAPTER 2: Now You See It, Now You Don’t

- CHAPTER 3: The Green Planet and the Red Heat

- CHAPTER 4: Hot Rays

- CHAPTER 5: Ultraviolet Brings the Blues

- CHAPTER 6: Danger Beyond the Violet

- CHAPTER 7: Energy Rhythms

- CHAPTER 8: The Exploding Sun

- CHAPTER 9: No Soap

- CHAPTER 10: Turning On and Tuning In

- CHAPTER 11: The Speed That Destroyed Space and Time

- CHAPTER 12: Microwaves Everywhere

- CHAPTER 13: The Man with the X-ray Vision

- CHAPTER 14: Röntgen Rays for Everyone

- CHAPTER 15: What’s in Your Basement?

- CHAPTER 16: The Atomic Quartet

- CHAPTER 17: Gamma Rays: The Impossible Light

- CHAPTER 18: Cell-Phone Radiation

- CHAPTER 19: Cosmic Rays

- CHAPTER 20: Beams from the Universe’s Birth

- CHAPTER 21: Energy from Our Minds

- CHAPTER 22: Ray Guns

- CHAPTER 23: The Next Frontier: Zero-Point and Dark Energies

- CHAPTER 24: Total Solar Eclipse: When the Rays Stop

- CHAPTER 25: ETs May Be Broadcasting, but What’s Their Number?

- CHAPTER 26: Does Light Have a Bright Future?

- Index

- Copyright