- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

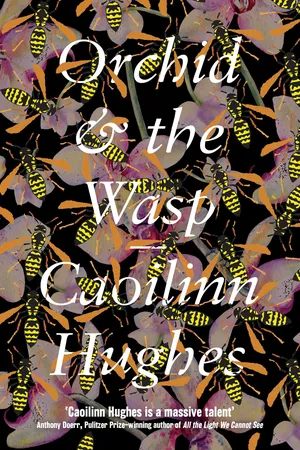

‘A gem of a novel’ Elle

‘A winning debut’ The New Yorker

‘Caoilinn Hughes is a massive talent.’ Anthony Doerr, Pulitzer Prizewinning author of All the Light We Cannot See

WINNER OF THE COLLYER BRISTOW PRIZE

Orchids are liars.

They use pheromones to lure wasps in to become unwitting pollinators. In nature, such exploitative systems are rare. In society, they are everywhere.

Gael Foess is a heroine of mythic proportions. Raised in Dublin by single-minded, careerist parents, she learns from an early age how ideals and ambitions can be compromised. When her father walks out during the 2008 crash, her family falls apart. Determined to build a life-raft for her loved ones, Gael sets off for London and New York, proving how little it takes to game the system - but is it really exploitation if the loser isn't aware of what he's losing?

Written in electric, heart-stopping prose, Orchid & the Wasp is a dazzlingly original novel about gigantic ambitions and social upheaval, chewing through sexuality, class and politics with joyful, anarchic fury, announcing Caoilinn Hughes as a rising star of literary fiction.

SHORTLISTED FOR THE BUTLER LITERARY AWARD * SHORTLISTED FOR THE HEARST BIG BOOK AWARDS 2019 * LONGLISTED FOR THE AUTHORS' CLUB BEST FIRST NOVEL AWARD * LONGLISTED FOR THE INTERNATIONAL DUBLIN LITERARY AWARD 2020

‘A winning debut’ The New Yorker

‘Caoilinn Hughes is a massive talent.’ Anthony Doerr, Pulitzer Prizewinning author of All the Light We Cannot See

WINNER OF THE COLLYER BRISTOW PRIZE

Orchids are liars.

They use pheromones to lure wasps in to become unwitting pollinators. In nature, such exploitative systems are rare. In society, they are everywhere.

Gael Foess is a heroine of mythic proportions. Raised in Dublin by single-minded, careerist parents, she learns from an early age how ideals and ambitions can be compromised. When her father walks out during the 2008 crash, her family falls apart. Determined to build a life-raft for her loved ones, Gael sets off for London and New York, proving how little it takes to game the system - but is it really exploitation if the loser isn't aware of what he's losing?

Written in electric, heart-stopping prose, Orchid & the Wasp is a dazzlingly original novel about gigantic ambitions and social upheaval, chewing through sexuality, class and politics with joyful, anarchic fury, announcing Caoilinn Hughes as a rising star of literary fiction.

SHORTLISTED FOR THE BUTLER LITERARY AWARD * SHORTLISTED FOR THE HEARST BIG BOOK AWARDS 2019 * LONGLISTED FOR THE AUTHORS' CLUB BEST FIRST NOVEL AWARD * LONGLISTED FOR THE INTERNATIONAL DUBLIN LITERARY AWARD 2020

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Orchid & the Wasp by Caoilinn Hughes in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Oneworld PublicationsYear

2018eBook ISBN

9781786073662Subtopic

Literature General1

The Mediocrity Principle

April 2002

It’s our right to be virgins as often as we like, Gael told the girls surrounding her like petals round a pollen packet.

‘Just imagine it,’ she said. ‘Louise. Fatima. Deirdre Concannon.’ She pronounced their names like accusations. She snuck the tip of her index finger into each of their mouths and made their cheeks go: pop. pop. pop. ‘I did mine already with this finger,’ she said. The girls flinched and wiped their taste buds on their pinafores. ‘Blood dotted the bathroom tiles but it wasn’t a lot and it wasn’t as sore as like … piercing your own ears without ice,’ she concluded ominously. ‘And now I don’t have to obsess over it like all these morons. You should all do it tonight. We’ll talk tomorrow and I’ll know if you’ve done it or not.’

Tiny hairs on their ears trembled at her inaudible breath, like Juliet’s. Gravely, she confessed: ‘Some of you will need capsules all your life. All the way to your wedding night because of being Muslim or really really Christian. Wipe your snot, Miriam. It’s a fact of life. It’s also helping people. Boys will think they’re taking something from you, when the capsule cracks. But you’ll know better,’ she said. ‘You’ll know there was nothing to take.’

Gael was eleven. It was her last term of primary school. Perhaps that was why the proposition backfired. The girls were getting ready to fly off to some other wealthy, witheringly beautiful leader. But Gael wasn’t disturbed by this. She no longer needed a posse. It would be tidier if they fell away than having to break them off.

‘Really really Christian like your brother?’ Deirdre replied. ‘Isn’t he an altar boy?’

Gael rolled her eyes so dramatically it gave her a back-of-socket headache. ‘He hasn’t got a hymen, Deirdre, so he’s obviously irrelevant.’

Deirdre and Louise’s mirth was exacerbated by the fact that Miriam’s tears had now formed a terracotta paste with the foundation she’d tried on at the bus-stop pharmacy earlier. How much would the virgin pills cost, Becca wanted to know. What would Gael price them at?

‘What-ever,’ Gael said. ‘What does that matter? Pocket money is what. Everyone’ll want them. Hundreds if not millions of people, Rebecca. So choose.’ She challenged their non-committal natures, looking from girl to concave girl. ‘Well, are you or aren’t you? In?’ She addressed the dandruffy crowns of their heads. Of late, they’d become less worthwhile spending time with. Even playing sports, they didn’t want to sweat. Headbutting nothing, the chimney-black sweep of her hair kicked forward and she thrust them off like a sudden squall that separates what’s flyaway from what’s fixture. Stupid girls, she thought as the lunch bell trilled and they straggled towards their classrooms. Back to times tables: the slow, stupid common operations.

Turning her back on the blackboard, she took a bottle of Tipp-Ex from her bag and began painting her nails a corrective white. It smelled of Guthrie’s bedroom. Acrid. Concentrated. Tissues fouled with paint from cleaning his brushes. Exoneration. Her little brother: the acolyte. On the ninth nail, she lifted her head from the fumes to find Deirdre Concannon striding into the room alongside the school counsellor, who approached Gael’s desk with a blob of tuna-mayo in the corner of her puckered mouth, a mobile phone held out and a polite invitation for Gael to take her depraved influence elsewhere. The number Gael dialled was familiar. Though, as Mum was out of town, it was to be an unfamiliar fate.

Jarleth had sent a car to collect them and take them to his work several hours ago. On the phone, his secretary had informed Gael as to the make of the car and the name of the driver. (Both Mercedes.) There’d been no chastisement thus far, other than an afternoon confined to a windowless meeting-room penitentiary in his office building.

In the same school but two years behind his sister, Guthrie had been encouraged to go home too when his whole class had concluded their post-lunch prayer in perfect unison: ‘And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil, Hymen.’ Gael was already waiting at the school gate when Guthrie had come dragging his satchel-crucifix across the tarmac, in utter distress and confusion.

His blue eyes were red-rimmed as a seagull’s by the time he finished his homework under the artificial lights of Barclays’ Irish headquarters at 2 Park Place in Dublin’s city centre, just around the corner (though worlds apart) from the National Concert Hall, where they often watched their mother yield a richer kind of equity from her orchestra.

Guthrie spoke quietly into his copybook. ‘You always do this when Mum’s gone.’

‘I said I’m sorry.’

‘But you’re not.’ He made a convincingly world-weary noise for a ten-year-old.

Their mother was principal conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra – one of Ireland’s two professional orchestras – with whom she gave some hundred concerts a year, on top of guest conductorships where she might perform eight shows in a week, hold interviews, benefits, meetings, recordings, travel … generally returning home prostrate.

Gael searched for Ys in the ends of her black hair. Absently, she said, ‘How was I to know my idea’d make all the sissies go berserk?’

Guthrie’s wispy, beige hair kissed the polished pine table where he rested his head on his arm. He was slowly translating Irish sentences from his textbook with his left hand. He was a ciotóg. A left-handed person. Meaning: ‘strange one’.

Fadó, fadó,

A long time ago

bhí laoch mór ann, ar a dtugtar Cúchulainn.

there was a great hero warrior of the name named called Cúchulainn.

He stopped writing and let the pencil tip rest on the page like a Ouija board marker. After a while, he lifted it and moved it to a blank page where he began drawing Cúchulainn in profile, sword brandished. It was a giant weapon with an intricate hilt. Guthrie gave his hero long flowing locks and a chain-mail vest and shin guards. When all the details had been filled in, Guthrie began to add squiggles all around the figure and wild loops in the air – childish in comparison to Cúchulainn’s frenzied expression.

‘Are they clouds?’ Gael asked.

A barely perceptible shift of his head.

‘Trees?’

‘Waves,’ he said softly.

‘Wait.’ She considered the sketch anew. ‘He’s in the sea? With those heavy clothes on?’

Guthrie exaggerated the hero’s grimace and drew a twisted cloak in place of saying yes. He strengthened the line of the chin and the nostril brackets, for defiance. ‘He’s fighting the ocean.’

Watching the pencil go, Gael wondered at this. Cúchulainn battling the humongous Atlantic. An invisible duel, in slow, deliberate motion. Had he no mind for reward or reputation, should he win? Or rescue, should he lose? Maybe he was just proving something to himself; testing the muscle of his character, no thought of audience. There aren’t viewing posts in towers of water. No adjudication. Why else would a person take on the tireless sea but to learn the strength of his own current? Guthrie lifted his head to reveal a pale yellow mark where his cheek had been pressed against his forearm.

‘That’s what it feels like,’ he said, evenly, erasing some lines from the drawing and brushing the grey rubber scraps to the floor. ‘The way you get dragged in the white part.’

‘What feels like that?’

Some moments passed without answer.

‘Oh,’ Gael said, realizing. ‘That doesn’t sound relaxing.’

‘It’s not.’

‘But you know it’s only gravity, dragging you down, right? It’s not like, a monster or Satan or anything.’

Guthrie seemed to think about this. ‘It’s me,’ he said.

‘The warrior?’

He shook his head and Gael half expected feathers of pale hair to come falling off, like when you shake a dead bird. ‘The one dragging.’

‘Guthrie! That’s not a good thing to think. It’s not your fault.’

Gael said this, though she knew it was a lie to make things liveable. Her parents had sat her down a few weeks ago to explain the situation. ‘Your brother doesn’t have epilepsy. He only thinks he does,’ Jarleth had said. Sive had looked dismayed by that explanation and had taken over. ‘It’s called somatic delusional disorder, Gael. I’m sure you’ll want to look it up. What’s important is that he’s physically healthy,’ she’d said, ‘but there’s one small, small part of his brain that isn’t well. The doctors say when he’s older, it might be easier to address him directly about it, with counselling. Right now, he gets extremely stressed and anxious, aggressively so, if we talk to him about the disorder. He thinks we’re telling him he’s not sick. Which he is, just not in the way he thinks. So it’s better for everyone to treat it as what Guthrie believes it to be. And that’s epilepsy.’ What Gael took from this was that her brother was too young to understand the truth and it was part of his sickness that he couldn’t.

‘Guth?’ Gael repeated, ‘It’s not your fault.’

‘Dad says so.’

A clout of anger to the chest. ‘Dad’s wrong.’

‘He’s mad at me.’

‘He’s just … frustrated to see you break something every time you have a fit.’

‘It’s not on purpose.’

‘I know.’

‘I don’t control it.’

‘I know that.’

‘If it was to … If I just wanted to skip PE, Miss McFadden would just let me do extra arts and crafts so long as I don’t plug stuff in or use scissors or knives or strong glue, she said I can. Or even something else.’

Gael made a shocked face. ‘She must’ve been drunk or something. McFadden’s a prick.’

‘She can tell that you think that. You make her mean. She said you’re arrogant but I told her you’re nicer when you’re not at school.’

‘Who cares about nice.’

‘She said, “That’s convenient.” ’

‘It’d be convenient if she got mad cow disease from a burger.’

‘Don’t, Gael.’ Tears surged in his eyes again. ‘I like her.’

‘Fine, sorry, I take it back! No mad cow disease for Miss McFadden. She’s probably vegetarian, Guthrie, don’t cry.’

‘It’s not–’ he said hoarsely.

Gael took his hand from his mouth, where he was chewing on the outer heel of his palm. ‘Don’t do that. Please tell me what’s wrong.’

He tried to explain, but sobbing hampers syntax. Gael pieced together the howled-out word clusters. Dad had warned him he’d have to be moved to Special School if he kept having fits. ‘But it’s … not special … special is … special … means …’

‘It’s a euphemism,’ Gael said. A word she’d learned recently and learned well.

Guthrie blinked at her rapidly. This was new information. ‘A what?’

‘A euphemism. Here.’ She took his pencil. ‘You learn it and say it to Dad if he ever threatens that again. You-fa-mism. It means when one word is just a nice way to say something worse. And it’s a lie, Guth. There’s no way you’d have to move schools.’

‘Dad wouldn’t just say it.’

‘He doesn’t see it as a lie. He sees it as a way to protect you. He’ll say whatever he thinks will work, to keep you safe. Does Mum know?’

‘What?’

‘Th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Mediocrity Principle

- 2 Sorry Is the Child

- 3 A Man Walks into a House

- 4 The Gates of Horn & Ivory

- 5 How to Price an Option

- 6 The Art of Integration

- 7 Opportunity, Cost

- 8 Non Zero Sum

- 9 Diminishing Returns

- Acknowledgements

- About The Author

- Copyright