- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A Sunday Times Book of the Year

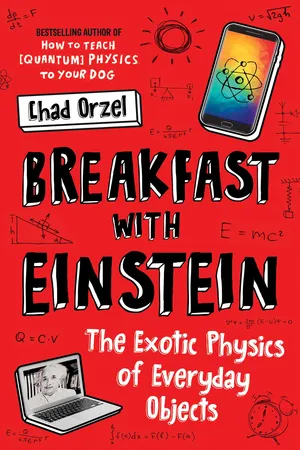

From the author of the international bestseller How to Teach Quantum Physics to Your Dog

Your humble alarm clock, digital cameras, the smell of coffee, the glow of a grill, fibre broadband, smoke detectors… all hold secrets about quantum physics.

Beginning at sunrise, Chad Orzel reveals the extraordinary science that underpins the simplest activities we all do every day, from making toast to shopping online. It’s all around us, the wonderful weirdness of quantum – you just have to know where to look.

From the author of the international bestseller How to Teach Quantum Physics to Your Dog

Your humble alarm clock, digital cameras, the smell of coffee, the glow of a grill, fibre broadband, smoke detectors… all hold secrets about quantum physics.

Beginning at sunrise, Chad Orzel reveals the extraordinary science that underpins the simplest activities we all do every day, from making toast to shopping online. It’s all around us, the wonderful weirdness of quantum – you just have to know where to look.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Sunrise: The Fundamental Interactions

The sun comes up not long before my alarm clock starts beeping, and I get out of bed to start the day …

It might seem like cheating to start a book on the quantum physics of everyday objects by talking about the sun. After all, the sun is a vast sphere of hot plasma, a bit more than a million times the volume of Earth, floating in space ninety-three million miles from here. It’s not an everyday object in the same way as, say, an alarm clock that you can pick up and throw across the room when it wakes you after a too-short sleep.

On the other hand, in a sense the sun is the most important everyday object of all, even beyond the glib observation that a day doesn’t start until the sun rises. Without the light we receive from the sun, life on Earth would be utterly impossible—the plants we rely on for food and oxygen wouldn’t grow, the oceans would freeze, and so forth. We’re dependent on the light and heat of the sun for our entire existence.

For the purposes of this book, the sun is also a useful vehicle for a kind of dramatis personae, introducing the key players of quantum physics: the twelve fundamental particles that make up ordinary matter, and the four fundamental interactions between them.

The twelve fundamental particles—particles that cannot be broken down any further into even smaller parts—are divided into two “families,” each with six particles. The quark family consists of the up, down, strange, charm, top, and bottom quarks, and the lepton family contains the electron, muon, and tau particles, along with electron, muon, and tau neutrinos. The four fundamental interactions are gravity, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear interaction, and the weak nuclear interaction. You can often find these particles and interactions enumerated on a colorful chart hanging in a physics classroom, collectively referred to by the sadly generic name “The Standard Model of physics.” The Standard Model encapsulates everything we know about quantum physics (and also about the ability of physicists to come up with catchy names), and ranks as one of the greatest intellectual achievements of human civilization.1 The sun is a perfect introduction to the Standard Model, because all four of the fundamental interactions have a role to play in order for the sun to shine.

So, we’ll start our story with the sun, taking a whirlwind tour of its inner workings to illustrate the essential physics that powers everything else we do. We’ll go through each of the fundamental interactions in turn, beginning with the best known and most obvious of these forces: gravity.

Gravity

If you were to generate sports-radio-style “power rankings” of the fundamental interactions of the Standard Model, three of the four have a decent case for claiming the top spot. If pressed to make a choice, though, I’d probably give the honors to gravity, because gravity is ultimately responsible for the existence of stars, and thus for most of the atoms making up our bodies and everything around us, enabling our silly conversations about ranking fundamental forces.

In our everyday lives, gravity is probably the most familiar and inescapable of the fundamental interactions. It’s gravity that you fight against when getting out of bed in the morning, and gravity that keeps me from being able to dunk a basketball (well, gravity, and being woefully out of shape …). We spend the vast majority of our lives feeling the pull of gravity, which makes its temporary absence—as in amusement park rides featuring sudden drops—fascinating, and even thrilling.

That familiarity also makes gravity one of the most-studied forces in the history of science. People have been thinking about how and why objects fall to the earth for at least as long as we have records of people pondering the workings of the natural world at all. Popular legend traces the origin of physics to a young Isaac Newton being struck (literally, in some versions) by the fall of an apple from a tree, and thus impelled to invent a theory of gravity. Contrary to the image conjured up by this apocryphal tale, though, scientists and philosophers were already well aware of gravity, and had devoted significant thought to how it works. By Newton’s day, experiments by Galileo Galilei, Simon Stevin, and others had even made some quantitative headway on the subject, establishing that all dropped objects, regardless of their weight, fall toward the earth with the same acceleration.

As an old man, Newton himself recounted a version of his apple encounter to younger colleagues. It isn’t mentioned in his papers from the time when he was actually working on gravity, but he did spend an extended time during that period at his family’s farm in Lincolnshire, when the universities were closed due to an outbreak of plague. To the extent that there’s truth to the story however, the most popular telling misidentifies the nature of Newton’s insight. Newton’s epiphany was not about the existence of gravity but its scope: he realized that the force pulling an apple to the ground is the same force that holds the moon in orbit about the earth, and the earth in orbit around the sun. In the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Newton proposed a universal law of gravitation, giving mathematical form to the attractive force between any two objects in the universe having mass. This form, combined with his laws of motion, allowed physicists to explain the elliptical orbits of the planets in the solar system, the constant acceleration of objects falling near the earth, and a host of other phenomena. It established a template for physics as a mathematical science, one that is followed right up to the modern day.

The crucial feature of Newton’s law of gravity is that the force between masses depends on the inverse of the distance between them squared—that is, if you halve the distance between two objects, you get four times the force. Objects that are closer together experience a stronger pull, which explains why the inner planets of the solar system orbit more rapidly. It also means that a diffuse collection of objects will tend to be drawn together, and as they grow closer, they are compressed ever more tightly by the increasing force of gravity.

This increasing force is critical for the continued existence of the sun, and it’s the ultimate source of its light. The sun is not a solid object, but rather a vast collection of hot gas, held together only by the mutual gravitational attraction of all the individual atoms making it up. While it may top our list in terms of everyday impact, gravity is the weakest of the fundamental interactions by a mind-boggling amount—the gravitational force between a proton and an electron is a mere 0.000000000000000000000000000000000000001 times the electromagnetic force that holds them together in an atom. The enormous quantities of matter present in the sun, however—some 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 kg—build up a gigantic, collective gravitational force, pulling everything nearby inward.

A star like the sun begins life as a small region of slightly higher density in a cloud of interstellar gas (mostly hydrogen) and dust. The extra mass in that region pulls in more gas, increasing its mass, and thus increasing the gravitational attraction to pull in more gas still. And, as new gas falls in toward the growing star, it begins to heat up.

At the microscopic scale, a single atom drawn toward a protostar speeds up as it falls inward, just like a rock dropping toward the surface of the earth. You could, in theory, describe the behavior of the gas in terms of the speed and direction of each of the individual atoms, but that’s ridiculously impractical even for objects vastly smaller than a sun-sized ball of gas—not just because of the number of atoms, but because the atoms interact with each other. A non-interacting atom would be drawn in toward the center of the gas cloud, speeding up as it went, then would pass out through the other side, slow down, stop, and turn around to repeat the process. Real atoms, though, don’t follow such smooth paths: they hit other atoms along the way. After a collision, the colliding atoms are redirected, and some of the energy gained by the falling atom as it accelerated due to gravity is transferred to the atom it hit.

For a large collection of interacting atoms, then, it makes much more sense to describe the cloud in terms of the collective property known as temperature. Temperature is a measure of the average kinetic energy of a material as a result of the random motion of the components making it up—for a gas, this is mostly a function of the speed of the atoms zipping around.2 An individual atom is pulled inward and accelerates, gaining energy from gravity and increasing the total energy of the gas. When it collides with other atoms, that energy is redistributed, raising the temperature. The total energy doesn’t increase, but rather than having a single, fast-moving atom passing through a bunch of slower ones, after many collisions, the average speed of every atom in the sample increases by a tiny amount.

The increasing speed of the atoms in the cloud of gas tends to push it outward, as a faster-moving atom can travel a greater distance from the center before gravity turns it around and brings it back in. The redistribution of energy from new atoms, though, means that this increase isn’t enough to stop the collapse, and as new atoms are pulled in, the mass of the protostar increases, increasing the gravitational force. This, in turn, draws in more gas, bringing in more energy and more mass, and so on. The cloud continues to increase in both temperature and mass, becoming denser and denser, and hotter and hotter.

Left unchecked, the growing force of gravity would crush everything down to an infinitesimal point, forming not a star but a black hole. While these are fascinating objects, warping space and time and presenting a major challenge to our most fundamental theories of physics, the environment near a black hole is not a hospitable place to have a weekday morning breakfast.

Happily, the other fundamental interactions have their own roles to play, halting the star’s collapse and allowing the formation of the sun we know and love. The next to kick in is the second most familiar: electromagnetism.

Electromagnetism

We regularly encounter the electromagnetic interaction in everyday life, whether in the form of static electricity crackling in a load of socks fresh from the dryer, or that of magnets holding grade-school artwork to the refrigerator. Unlike gravity, which is always attractive, electromagnetism can be either attractive or repulsive—electric charges come in both positive and negative varieties, and magnets have both north and south poles. Opposite charges or poles attract each other, while like poles or charges repel. The electromagnetic interaction is even more ubiquitous than static charges and magnets, though—in fact, it’s responsible for our ability to see, well, anything.

In the early 1800s, electromagnetism was a ...

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 • Sunrise: The Fundamental Interactions

- Chapter 2 • The Heating Element: Planck’s Desperate Trick

- Chapter 3 • Digital Photos: The Patent Clerk’s Heuristic

- Chapter 4 • The Alarm Clock: The Football Player’s Atom

- Chapter 5 • The Internet: A Solution in Search of a Problem

- Chapter 6 • The Sense of Smell: Chemistry by Exclusion

- Chapter 7 • Solid Objects: The Energy of Uncertainty

- Chapter 8 • Computer Chips: The Internet Is for Schrödinger’s Cats

- Chapter 9 • Magnets: How the H*ck Do They Work?

- Chapter 10 • Smoke Detector: Mr. Gamow’s Escape

- Chapter 11 • Encryption: A Final, Brilliant Mistake

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Breakfast with Einstein by Chad Orzel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Physics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.