- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

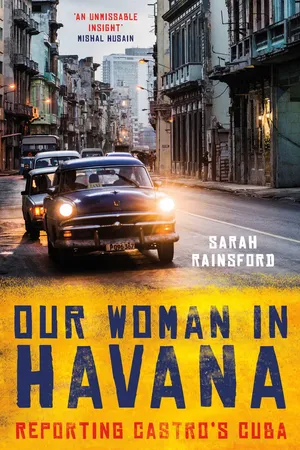

Graham Greene saw the Castros rise; Sarah Rainsford watched them leave.

From the street where Wormold, the hapless hero of Greene’s Our Man in Havana, plied his trade, BBC foreign correspondent Rainsford reports on Fidel’s reshaping of a nation, and what the future holds for ordinary Cubans now that he and his brother Raul are no longer in power.

Through tales of literary ghosts and forgotten reporters, believers in the revolution and dissidents, entrepreneurs optimistic about the new Cuba and the disillusioned still looking for a way out, Our Woman in Havana paints an enthralling picture of this enigmatic country as it enters a new era.

From the street where Wormold, the hapless hero of Greene’s Our Man in Havana, plied his trade, BBC foreign correspondent Rainsford reports on Fidel’s reshaping of a nation, and what the future holds for ordinary Cubans now that he and his brother Raul are no longer in power.

Through tales of literary ghosts and forgotten reporters, believers in the revolution and dissidents, entrepreneurs optimistic about the new Cuba and the disillusioned still looking for a way out, Our Woman in Havana paints an enthralling picture of this enigmatic country as it enters a new era.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Our Woman in Havana by Sarah Rainsford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Media & Communications Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Without Haste

‘Psssst! Papa quiere?’ I jumped as the man passing me hissed suddenly under his breath. Do I want a Daddy? I wondered, confused as the man beckoned. It was the middle of the day in a busy street so I calculated that this stranger wasn’t about to force ‘Daddy’ onto me and I followed. Round the corner he thrust a lumpy carrier bag towards me and named his price. Inside were a couple of kilos of potatoes, or papas. It clearly wasn’t only Cuban Spanish I needed an induction in, but how to shop.

The man had approached me outside the best farmers’ market in Havana: the socialist, not the hipster sort. When we made it inside my husband was accosted by a tall black transvestite in a skin-tight top calling him guapo near a table displaying a pig’s head split in two. She persisted in trying to lure him away until the pork sellers took pity and disentangled him.

The markets were one of communist-run Cuba’s earliest liberalising economic experiments, freeing up farmers to sell some produce direct to customers and not just the state. The stalls were heaped with giant avocados, mangoes and more, depending on the season, but I could never find potatoes. I eventually discovered that what didn’t go to the all-inclusive tourist resorts was usually diverted to the black market. On the rare occasions potatoes did make it to the shops there’d be enormous queues and even fights. The deficit spawned a very Cuban joke when Pope Benedict visited the island in 2012. ‘Papa’s arrived!’ people would say. ‘How much per pound?’ was the reply.

The dearth of potatoes was one of the many mysteries of Cuba I had to adjust to when I arrived to report from the island. I’d landed in Havana on a sweltering Christmas Eve to an airport full of border guards in short skirts and extravagantly patterned tights. As they flicked unhurriedly through our passports, the women teased and called out to one another as mi amor. One of them, perhaps the girl with pink-dyed hair, then handed our documents back and waved me and my husband through. Welcome to Cuba. After encountering my first communist entrepreneur in the Ladies’ – requesting ‘notes please, not coins’ for a square of toilet tissue – we were soon squeezing through the crowds into the street.

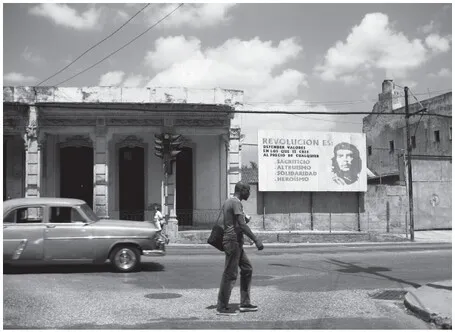

The drive was my first sight of Havana, a sprawling city of over two million people or around a fifth of Cuba’s population. On the outskirts we passed low-rise houses in bright clashing colours and a maternity hospital shaped like a woman’s ovaries when viewed from above. Overtaking the hulking 1950s American cars that run through the city as shared taxis, we soon pulled into the upmarket neighbourhood of Miramar. Before the revolution this was where Havana’s English-speaking expat community rubbed shoulders with the white Cuban elite. In modern-day Cuba some people were scraping by in cramped rooms down shadowy passageways while others kept neat detached homes behind tall fencing and cactus hedges on Calle 70, a two-lane street that swept down to the sea.

For the first few weeks, as we looked for long-term accommodation, we made our base there in a hotel-cum-apartment complex with a psychedelic paint job. My advance impressions of Havana had been heavily influenced by the steamy Dirty Havana Trilogy of Pedro Juan Gutierrez, a novel that gave me visions of a city oozing with sweaty sexuality. Our own dazed and jet-lagged first evening in Havana was spent eating deep-fried cheese sticks dipped in brown sauce in a lobby bar hung with images of Laurel and Hardy alongside Cuba’s revolutionaries.

Tranquil Miramar was far from the dirty realist world of Gutierrez. There was a park where children could take horse rides and teenagers got free martial arts classes. Some weekends souped-up vintage American cars would challenge Soviet Ladas to drag races along a side road lined by a cheering crowd. Walking anywhere at night was an obstacle course with minimal street lighting and paving stones ripped apart by giant ceiba tree roots stretching like gnarled fingers. Most of the manhole covers were missing, presumably taken to sell for scrap like the metal inscription picked off an unflattering bust of Yasser Arafat the very first night it appeared on our street.

I did have ideas of moving out of the suburbs for what I imagined then would be a more ‘authentic’ Cuban experience. I’d pictured us renting a flat in a Spanish colonial-era building in Old Havana with shutters and wooden ceiling fans, and son music floating up from some neighbourhood bar. But the reality of life in the old city turned out to be less romantic, all power cuts and tourists and bands strumming ‘Guantanamera’ on a relentless loop. As a foreign correspondent I didn’t have much choice of accommodation in any case. We had to rent from the state, a rule I assumed was to help the authorities keep tabs on us as well as being an easy source of cash. Some journalists would take on entire rundown houses and spend months repairing and kitting them out at great stress and cost. When they left, those revamped homes would revert to the state. With neither the budget nor the patience for such a deal, we ended up moving into a modern apartment block reserved for foreigners. Instead of the Buena Vista Social Club it was the anguished hits of Adele that wafted up to my balcony.

***

Apart from the farmers’ markets, the clearest sign of reform in those early days was the privately run house-restaurants, or paladares. They first appeared in the 1990s as Cuba reluctantly reopened the island to mass tourism. Prising the economy open to private business was equally uncomfortable for the revolutionary government, but it was forced to adapt to survive. The collapse of the USSR had deprived Cuba of an economic prop worth an estimated $5 billion per year, and the state alone could no longer provide.

In the early days the paladares were so encumbered by regulations that many went to the wall. When I arrived in Havana, there were only a handful in my neighbourhood and most served dry fish fillets or pork on oversized plates with a swirl of jam to appear cutting-edge. Over the next three years, the change was dramatic. As Raul Castro allowed the private sector to expand, Miramar got good Italian restaurants, nightclubs and burger bars. On Calle 70, people began selling CDs and offering haircuts on their porches, and one house was partially converted into a gym.

While private enterprise took off, Cuba’s centrally planned state economy remained inefficient and underfunded. It was also struggling under an economic embargo first imposed by the US in 1960 and intended to strangle the revolution at birth. Underestimating the impact of all that on daily life, I’d arrived from Madrid with just a couple of suitcases. I then spent weeks scouring Havana’s ill-stocked stores trying to replace what I’d blithely left in storage. ‘Excitement today as I found sponges in a shopping centre’, I noted one day in the diary I kept sporadically.

Hunting for the basics, I also had to get my head round the dual currency system. State workers were paid in Cuban pesos, or CUP, earning the equivalent of around $20 a month. But all stores selling anything worth buying operated in convertible pesos, or CUC, and the prices were at least as high as in Europe. The system dated back to the 1990s when the government legalised use of the US dollar so that tourists could inject some hard currency into the local economy. The dollar was eventually replaced by the CUC, pegged to the US currency, and by my time on the island almost everything from cooking oil to clothes was sold in CUC. The farmers’ markets were a rare exception but that didn’t make them cheap. A pound of onions would cost fifteen CUP, roughly a day’s wage for a state worker. When I asked Cubans how they coped, they’d shrug and smile, and then utter what I learned was the national mantra. No es facil. It’s not easy.

My early weeks in Havana continued in a blur of impressions and shattered stereotypes. There was a trip to immigration to be fingerprinted for my ID card by cheerful women in military miniskirts and a Jehovah’s Witness taxi driver who presented me with a dog-eared copy of The Watchtower. There were girls in Lycra leggings printed with the American flag and an elderly Cuban woman wandering Miramar in a ‘Crimestoppers UK’ T-shirt. Then there was a former Havana correspondent who warned me that I should trust no one, recounting a story about being befriended by a ‘spy’ who stole his wife’s underwear. Back at our state-owned flat, I began to wonder whether the drawer of the cabinet beside our bed was glued shut to conceal a listening device or just because the front was dodgy and would otherwise fall off.

***

Early on in my stay I dreamed about a chance meeting with Fidel. ‘Offered an exclusive up-close-and-personal documentary’, I scribbled down when I woke. ‘Excited at the chance of access’. But such dreams were the closest I got to the ailing, reclusive Comandante. His brother Raul proved to be only slightly more accessible. I once arrived at Havana airport at 6 a.m. for the chance to see him as he accompanied the Iranian president to his plane after an official visit. I spent three hours drinking grainy coffee in a stuffy room with other foreign journalists before a Communist Party official released us onto the tarmac with stern instructions to conduct ourselves ‘respectably’ and give a ‘good impression’ of Cuba.

Our small press pack ended up behind a rope close to Ahmadinejad’s plane. ‘Shall we take a question?’ Raul wondered out loud as the two men approached our huddle, and we all began to shout. ‘Ah yes, TeleSur!’ he exclaimed, directing his guest towards the TV channel co-sponsored by Cuba and Venezuela, its socialist ally. There was growing talk in the West at the time of tightening sanctions against Iran over its nuclear programme. But the TeleSur correspondent had his own concern. ‘How was Fidel, when you saw him?’ Assuring the cameras that the elder Castro was ‘fit and well’, Ahmadinejad was then led off to his plane, my own shouted question left hanging.

Moments later, though, Raul was heading back towards us. Fidel was famous for making long public speeches in his healthy days but his brother usually kept his distance from the TV cameras. This then was a rare opportunity. But just as Raul began to reply to our questions, Ahmadinejad’s plane revved its engines and drowned out almost every word. Cuba’s leader was soon whisked away by his bodyguards. Back inside the airport terminal I crouched over my recording. I could just about hear Raul joking about his brother’s good health over the roar of the plane engines, but when answering a question on economic reform, his comments sounded cautious. For many Cubans the pace of change Raul had initiated was excruciatingly slow and that day their president gave no hope that it would pick up. As Ahmadinejad’s plane taxied along the tarmac, Raul told us that change would come ‘without pause, but without haste’.

***

‘Without haste’ was a phrase that seemed to sum up my work life in Cuba. A team linked to the Foreign Ministry known as the Centro de Prensa Internacional, or CPI, handled all requests for access or interviews. As the overwhelming majority of activities and institutions in Cuba were still state-controlled, I needed CPI permission to film everything, from farms to dance studios to supermarkets. I soon learned not to promise my editors in London anything until I had most of the footage in the bag.

In my first month I sent a long wish list to the CPI including requests for interviews about an anti-corruption drive. I asked about the restrictions on emigration as one of Cuba’s best-known dissidents, the blogger Yoani Sanchez, was repeatedly blocked from leaving the island. I also tried to get comment on new efforts to drill for oil, potentially rescuing the economy from crisis. I was rarely denied access outright; requests judged unsuitable were simply left pending. Meanwhile, I’d get regular emails from the CPI inviting me to events they imagined I might care to cover.

Email Invitation, 15 October 2012

Esteemed colleague:

The Ministry of Construction (MICONS) invites you to participate in a meeting on . . . perspectives for production of new construction systems using expanded polystyrene.

Taxi drivers were among my favourite conversation targets in the early days as I tried to learn as much about the island as I could, though my over-earnest efforts weren’t always productive. Attempting to get a Lada driver’s thoughts on the new oil rig one day, I realised he was more interested in catching my eye in his rear-view mirror. ‘He stared at me and proclaimed, “You’re so pretty, you have lovely eyes!” ’ I recorded in my diary....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Endings

- Part I

- 1 Without Haste

- 2 The Ruins of Havana

- 3 Confessions of a Martini Drinker

- 4 Consumption Anxiety

- 5 Connecting Cuba

- 6 The Sleeping Faith

- 7 Red Lines

- 8 Entertainments and Commitments

- 9 Condoms and Cricket

- 10 Adela

- 11 The Forgotten Reporter

- 12 Ways of Escape

- Part II

- 13 Film Crews and Firing Squads

- 14 Love not Money

- 15 Enemies and Allies

- 16 Cuba Libre

- 17 Athenian Forum

- 18 Sympathetic Visitor

- 19 The Case of Oswaldo Paya

- 20 Exile

- 21 Let’s Dance

- 22 The End of the Affair

- 23 Nice Girl from Vedado

- 24 Sierra Maestra

- Slow Erosion

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Imprint Page