- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

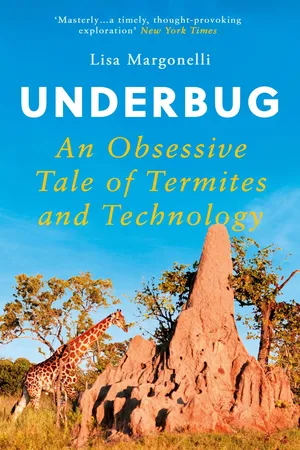

Who has the answer to the world's fuel problems? How can we bring ruined land back to life? Where do roboticists turn when they try to engineer a hive mind?

Termites.

Strange though it seems, scientists look to tiny termites for answers to some big ideas. Lisa Margonelli tracks them, deep into their mounds to find out how termites can change the world. Underbug: An Obsessive Tale of Termites and Technology touches on everything from meditation, innovation and the psychology of obsession to good old-fashioned biology.

Termites.

Strange though it seems, scientists look to tiny termites for answers to some big ideas. Lisa Margonelli tracks them, deep into their mounds to find out how termites can change the world. Underbug: An Obsessive Tale of Termites and Technology touches on everything from meditation, innovation and the psychology of obsession to good old-fashioned biology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Underbug by Lisa Margonelli in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

A TERMITE SAFARI

ARIZONA

IN JULY 2008, I RENTED a small yellow car in Tucson, Arizona, and drove it south toward Tombstone. There were three passengers in my car, and I was following a white van with government plates carrying nine more. Between these two vehicles we had eleven microbial geneticists from six countries with nearly three hundred years of collective education. We also had five hundred plastic bags, a thermos of dry ice, and three hundred fifty cryogenic vials, each the size and shape of a pencil stub. We had two days to get ten thousand termites.

I was there because I’d received an email titled “Termite Safari?” from Phil Hugenholtz, a researcher at the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (JGI). Earlier that year I’d done a story for The Atlantic about Phil and thirty-eight other scientists who sequenced a million genes from the microbes found in the guts of Nasutitermes corniger—termites they’d found in trees in Costa Rica. Because termites are famously good at eating wood, the genes in their guts were attractive to government labs trying to turn wood and grass into fuel: “grassoline.” The white van and the geneticists all belonged to JGI.

As I drove, the price of gasoline in the US was more than four dollars a gallon, the highest it had ever been. America, maybe the world, was spinning into a financial crisis, and a vicious presidential race was on. In those days, gasoline was always on my mind because I’d written a book about oil. When I received Phil’s email, I had been writing about the problems of petroleum for seven years, and I was staring at twenty open PDFs about energy on my computer’s desktop. I was at the end of my rope, both as an oil-consuming citizen and as a human being. Oil’s troubles are systemic, dating back at least a hundred years—and they’re made much nastier by modern politics. Termite Safari? Sure! Anything was better than sitting at my desk and thinking about oil.

Microbial geneticists are young and goofy: they sincerely believe in the scientific method and they blink in the sun. Phil, who led the lab with a jangly self-deprecating pride, called them “gene jockeys.” They lived in statistics and databases and thought in codes, both computer and genetic. Their organization was so antihierarchical that I sometimes had to tell them to stop bickering. “Stop it or I’ll turn this car right around,” I’d say.

Left on their own, the geneticists would never find ten thousand termites. They might not even find one hundred. North American termites are cryptic in the extreme: they live in tunnels underground and inside wood. So Rudi Scheffrahn, one of the country’s leading termite experts, sat in the passenger seat next to me, charting a course to the bugs.

He wore bifocals over his sunglasses while he scoured the last survey of termites in the area, published in 1934, around the time of the building of the Hoover Dam. Funded by a sugar refiner, along with lumber, railway, and electric companies, the survey hired entomologists to figure out which bugs might try to eat the electrical poles, bridges, and railway trestles that industry was erecting across California, Nevada, Arizona, and Mexico.

When Rudi sensed termites in the landscape, his sunburned knees began to twitch, which jiggled his head, sending little triangles of reflected light from his two pairs of glasses ricocheting around the rental car. It felt like a party.

When there were no termites, he seemed depressed. We drove past a lake. “Probably a nice place,” he said, in a flat, declining tone. “But there’s no termites there.”

Rudi is a termite chauvinist. He talked world records. Oldest insect: termite queens can live to be twenty-five years old, maybe more, no one knows. Fastest animal: some soldier termites slam their mandibles shut at 120 miles an hour, faster than a cheetah runs. Biggest terrestrial structures: mounds in Africa, Asia, and Australia can be up to thirty feet high. And about termites’ reputation as pests? Only twenty-eight out of twenty-eight hundred species are invasive pests, and Rudi believes that the first destructive drywood termites traveled from Peru on Spanish ships in the 1500s. Not their fault.

The geneticists in the back of the car laughed politely. They were not here to appreciate termites; they were here to appropriate them. Termite guts are a molecular treasure chest: 90 percent of the organisms in them are found nowhere else on Earth. The purpose of this trip was to gather the termites and their microbial mush in the vials and jam them into the dry ice before the genetic information they held deteriorated. The geneticists didn’t just want the microbes’ DNA, they also wanted the molecules of RNA, which could tell them which parts of the genetic code were in use at the precise moment the termites took their tumble into the thermos. Perhaps by seeing exactly how termites break down wood, we’d be able to do it, too.

If this trip succeeded in capturing a few good molecular moments, humans might eventually be able to power our cars without worsening climate change, or make fuel without drilling in national parks or causing oil spills. This trip could change the world—or at least the lives of the scientists in the cars.

We barreled down a long hill toward a scrub basin when Rudi’s legs began to twitch. The reflections from his glasses whizzed around the interior of the car. “I look out here and I just see billions of termites.”

JUST BEFORE I got interested in termites, they lost the identity—the distinctive order Isoptera—that they’d had for the last 175 years. In 2007 a paper was published called “Death of an Order: A Comprehensive Molecular Phylogenetic Study Confirms That Termites Are Eusocial Cockroaches.” And just like that, termites became homeless and nameless, demoted to gregarious cockroaches, very distant cousins of the praying mantis. Maybe more important, they were suddenly defined not by what they looked like, but by their genes. Their relationship to the most despised of bugs wasn’t news: it was first explored in the 1920s, and became obvious with DNA sequencing by 2000 or so, but it wasn’t considered a fact until 2007.

Here’s a possible story of how termites came to be—and why we were chasing them across Arizona. Once upon a time, cockroaches were solitary scavengers that ate fruit, rotten leaves, fungi, and bird droppings. They developed their eggs in beautiful bean-like sacs, shot them out their backsides at high speeds, and walked away, leaving their young to fend for themselves.

Sometime between 250 million and 155 million years ago, termites evolved from the chassis of these ancient roaches when some of them ate microbes that were able to digest wood. Wood was plentiful, but to survive on it the bugs needed to have those microbes handy at all times. The problem was that they regularly molted their intestines, which cleaned the microbes right out. Our evolving cockroaches started to exchange what entomologists politely call “woodshake”—a slurry of feces, microbes, and wood chips—among themselves, mouth to mouth and mouth to butt. After they pooled their digestion, it was a quick trip to constant communal living. One for all and all for one: Termites forever!

Termites’ twin innovations—wood-eating microbes and eusociality—are each worthy of an invertebrate Nobel Prize, but millions of years of evolution refined them still further. While the dinosaurs stomped around outside, these proto-termites evolved inside their dark logs, improving their togetherness by communicating through chemicals, sound, and touch. The queen, who produced all of the eggs for a colony, secreted chemicals that kept most of her children from reproductively maturing. Most of them were workers, gathering food, feeding the queen and the young, and doing tasks around the nest, but some differentiated into what we call soldiers, with ingenious strategies to better sacrifice themselves for the survival of the colony: nozzles filled with noxious chemicals on their heads, slashing mandibles, or big wedgy heads they could use to seal off passageways from invaders. Without the need to reproduce, or to venture far above ground, both worker and soldier termites lost things they didn’t need: eyes, wings, and big, tough exoskeletons.

By the time Pangaea split up and an ocean grew in between Brazil and Africa, termites were well positioned to evolve in ever weirder ways on different continents, in a big belt stretching around Earth at the equator and extending halfway to the North and South Poles.

FROM TOMBSTONE WE drove south to Bisbee, Arizona, and then toward the border with Mexico, stopping whenever Rudi felt termites. I finally found some on my own in the Coronado National Forest, when I wandered far from the road in the higher-altitude desert there. The light was pinkish and flat and the air smelled lightly of sage. Rudi said to look for termites under rocks because they’d be orienting themselves thermally. So I threw over a flat rock and got down on the ground. To capture the termites I had an aspirator—a homemade contraption consisting of a test tube, a tiny air filter, and some tubing—that allowed me to suck up specimens without getting a mouthful of termite.

Under the first rock I saw only beetles, grubs, white spiders, millipedes, and ants. When I looked up, I saw a white Homeland Security truck with a cage on the back, roaming the land like a human aspirator. In a gully were old sneakers, flattened Mylar hydration packs, and other evidence that some person or persons had come through from the border with Mexico. I hated to think of someone hiding, dehydrated, in this no-man’s-land. My phone chuckled intermittently, delivering texts that said I’d crossed into Mexican telephonic space and different rates would apply. The scrub here was barer than in other places we’d stopped. I wondered if it was recently vacated or secretly occupied. I didn’t so much feel eyes upon me as I felt an uncanny tingle.

The landscape made me feel dumb and clumsy. If I had to be dumb, I wanted to be systematic about it. I began turning over every stick, rock, and rotten cactus in my path. Termites had chewed the underside of most sticks and left behind eerie little wooden galleries—ghost towns with tiny, sticky dust webs fluttering like tattered lace curtains.

I had almost forgotten I was searching when I lifted a rock and saw a glint of glossy exoskeleton flowing into some little tunnels. I dropped to my knees and began sucking on the aspirator, a disgusting process that stimulated saliva production and made me dizzy. Two minutes later there were no more termites on the ground and I had about twenty-five in the test tube attached to the aspirator.

After the long hunt, my pale termites were disappointing. When I separated one from the clutch, it was less substantial than a baby’s fingernail clipping. Doddering around blindly, it waved the flimsy antennae on its bulbous head. In its stubby, translucent body I could almost see its coiled guts—and presumably whatever it had eaten for lunch. Ants have snazzy bodies with three sections, highlighted by narrow waists, like pinup models’, between the segments. Termites, which are no relation to ants or bees, have round, eyeless heads, thick necks, and teardrop-shaped bodies. And they long ago lost the cockroaches’ repulsive dignity, gnarly size, and gleaming chitinous armor. I put the termite back in the test tube.

What had I just sucked up? My little gang of twenty-five was incapable of doing much of anything. Without a colony, they had nowhere to bring food to, and thus no reason to forage. Without a crowd of soldiers, they couldn’t defend themselves. Without a queen, they couldn’t reproduce. Twenty-five termites are insignificant in the scheme of life and death and reproduction. Meaningless. What’s more, they were clinging to one another, making an icky beige rope of termite heads, bodies, and legs reminiscent of the game Barrel of Monkeys. In the miniature scrum I couldn’t even see a single termite—they looked like a clot, not a group of individuals. Or perhaps I’d found a single individual who happened to have twenty-five selves.

I’d stumbled into one of the big questions termites pose, which is, roughly, what is “one” termite? Is it one individual termite? Is it one termite with its symbiotic gut microbes, an entity that can eat wood but cannot reproduce on its own? Or is it a colony, a whole living, breathing structure, occupied by a few million related individuals and a gazillion symbionts who collectively constitute “one”?

The issue of One is profound in every direction, with evolutionary, ecological, and existential implications. The word used to describe this many-in-one phenomenon these days is “supe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Part V

- Part VI

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- Copyright