eBook - ePub

Natural History of the Farm

A Guide to the Practical Study of the Sources of Our Living in Wild Nature

- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Natural History of the Farm

A Guide to the Practical Study of the Sources of Our Living in Wild Nature

About this book

This is a guide to the practical study of the sources in wild nature of our living. It contains a series of study outlines for the entire year, and deals with both the plants and animals of the farm-the things that men have chosen to deal with as a means of livelihood and of personal satisfaction in all ages.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Natural History of the Farm by James G. Needham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Natural History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I. MOTHER EARTH

“Brother, listen to what we say. There was a time when our forefathers owned this great land. Their seats extended from the rising to the setting sun. The Great Spirit had made it for the use of the Indians. He had created the buffalo and the deer and other animals for food. He had made the bear and the beaver. Their skins served us for clothing. He had scattered them over the country and had taught us how to take them. He had caused the earth to produce corn for bread. All this he had done for his red children because he loved them.”

—From the great oration of “Red Jacket,” the Seneca Indian, on The Religion of the White Man and the Red.

If you ever read the letters of the pioneers who first settled in your locality when it was all a wilderness (and how recent was the time!), you will find them filled with discussion of the possibilities of getting a living and establishing a home there. Were there springs of good water there? Was there native pasturage for the animals? Was there fruit? Was there fish? Was there game? Was there timber of good quality for building? Was the soil fertile? Was the climate healthful? Was the outlook good? Has it ever occurred to you how, in absence of real-estate and immigration agencies, they found out about all these things?

They sought this information at its source. They followed up the streams. They foraged: they fished: they hunted. They measured the boles of the trees with eyes experienced in woodcraft. They judged of what nature would do with their sowings by what they saw her doing with her own native crops. And having found a sheltered place with a pleasant outlook and with springs and grass and forage near at hand, they built a dwelling and planted a garden. Thus, a new era of agriculture was ushered in.

Your ancestors were white men who came from another continent and brought with them tools and products and traditions of another civilization. Their tools, though simple, were efficient. Their axes and spades and needles and shears were of steel. Their chief dependence for food was placed in cereals and vegetables whose seeds they brought with them from across the seas. Their social habits were those of a people that had long known the arts of tillage and husbandry: their civilization was based on settled homes. But they brought with them into the wilderness only a few weapons, a few tools, a few seeds and a few animals, and for the balance and continuance of their living they relied upon the bounty of the woods, the waters and the soil.

A little earlier there lived in your locality a race of red men whose cruder tools and weapons were made of flint, of bone and of copper; who planted native seeds (among them the maize, the squash, and the potato), and whose traditions were mainly of war and of the chase. These were indeed children of nature, dependent upon their own hands for obtaining from mother earth all their sustenance. There was little division of labor among them. Each must know (at least, each family must know) how to gather and how to prepare as well as how to use.

Today you live largely on the products of the labors of others. You get your food, not with sickle and flail and spear, but with a can-opener, and you eat it without even an inkling of where it grew. So many hands have intervened between the getting and the using of all things needful, that some factory is thought of as the source of them instead of mother earth. Suppose that in order to realize how you have lost connection, you step out into the wildwood empty-handed, and look about you. Choose and say what you will have of all you see before you for your next meal? Where will you find your next suit of clothes and what will it be like? Ah, could you even improvise a wrapping, and a string with which to tie it, from what wild nature offers you?

These are degenerate days. One had to know things in order to live in the days of the pioneer and the Indian. But now one may live without knowing anything useful, if he only possess a few coins of the realm and have access to a department store.

“Back to nature” has therefore become the popular cry, and vacations are devoted to camping out, and to “foraging off to the country” as a means of restoration. But fortunately it is not necessary to go to the mountains or to the frontier in order to get back to nature; for nature is ever with us at home. She raises our crops with her sunshine and soil and air and rain, and turns not aside the while from raising her own. While we are engrossed with “developing” our clearings and are planting farms and cities and shops, she goes on serenely raising her ancient products in the bits of land left over: in swamp and bog, in gulch and dune, on the rocky hillside, by the stream and in the fence row. There she plants and tends her cereals and fruits and roots, and there she feeds her flocks. Wherever we leave her an opening, she slips in a few seeds of her own choosing, and when we abandon a field, she quickly populates it again with wild things. They begin again the same old lusty struggle for place and food, and of our feeble and transient interference, soon there is hardly a sign.

As for the wild things, therefore,—the things that so largely made up the environment of the pioneer and the red man—we need but step out to the borders of our clearing to find most of them. If any one would share in the experience of primeval times, he must work at these things with his own hands. To gain an acquaintance he must apply first his senses and then his wits. He must test them to find out what they are good for, and try them to find out what they are like: he must sense the qualities that have made them factors in the struggle for a place in the world of life. Thus, one may get back to nature. Thus, one may re-acquire some of that ancient fund of real knowledge that was once necessary to our race, and that is still fundamental to a good education, and that contributes largely to one’s enjoyment of his own environment.

FIG. 1. Metric and English linear measure.

The best place to begin is near home. Any large farm will furnish opportunities. It is the object of the lessons that follow to help you find the wild things of the farm that are most nearly related to your permanent interests, and to get on speaking terms with them. You will be helped by these studies in proportion as your own eyes see and your own hands handle these wild things. The records you make will be of value to you only as you write into them your own experience: write nothing else.

Suggestions to students: The regular field work contemplated in this course makes certain demands with which indoor laboratory students may be unfamiliar. A few suggestions may therefore be helpful:

1. As to weather: All weather is good weather to a naturalist. It is all on nature’s program. Each kind has its use in her eternal processes, and each kind brings its own peculiar opportunities for learning her ways. Nothing is more futile than complaint of the weather, for it is ever with us. It were far better, therefore, to enter into the spirit of it, to make the most of it and to enjoy it.

2. As to clothes: Wear such as are strong, plain and comfortable. There are thorns in nature’s garden that will tear thin stuffs and reach out after anything detachable; and there are burs, that will cling persistently to loose-woven fabrics. Kid gloves in cold weather and high heels at all times are an utter abomination. Clothing suited to the weather will have very much to do with your enjoyment of it and with the efficiency of your work.

3. As to tools: A pocket lens and a pocket knife you should own, and have always with you. A rule for linear measurements is printed herewith (fig. 1). Farm tools, furnished for common use, will supply all other needs.

4. As to the use of the blanks provided: Blanks, such as appear in the studies outlined on subsequent pages, are provided for use in this course. Take rough copies of them with you for use in the field, where writing and sketching in a notebook held in one’s hand is difficult; then make permanent copies at home. When out in the rain, write with soft pencil and not with ink.

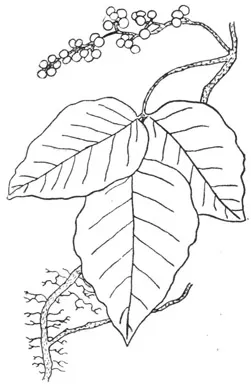

FIG. 2. Poison Ivy.

5. As to poison ivy (fig. 2): Unless you are immune, look out for it: a vine climbing by aerial roots on trees and fences, or creeping over the ground. Its compound leaves resemble those of the woodbine, but there are five leaflets in the woodbine, and but three in poison ivy. Lead acetate (sugar of lead) is a specific antidote for the poison; a saturated solution in 50% alcohol should be kept available in the laboratory. It is rubbed on the affected parts—not taken internally, for it also is a poison. If used as soon as infection is discoverable, little injury results to the skin of even those most sensitive to ivy poison. After lesions of the skin have occurred, through neglect to use it promptly, it is an unsafe and ineffective remedy; a physician should then be consulted.

6. As to pockets: Some people don’t have any. But containers of some sort for the lesser things, such as twigs and seeds, studied in the field, will be very desirable. You will want to take another look at them after you get back; so prepare to take them home, where you can sit at a table and work with them. A bag or a basket will hold, besides tools, a lot of stout envelopes, for keeping things apart, with labels and necessary data written on the outside.

7. As to reference books: “Study nature, not books”, said the great naturalist and teacher, Louis Agassiz. By all means, get the answers to the questions involved in your records of these studies direct from nature and not from books. But while you are in the field, you will meet with many things about which you will wish to know. Ask your instructors freely. Get acquainted, also, with some of the standard reference books, which will help you when instructors fail. Only a few of the more generally useful can be mentioned here.

There are three classical manuals for use in the eastern United States and Canada, that have helped the naturalists of several generations. These are Gray’s Manual of Botany, Jordan’s Manual of the ...

Table of contents

- Preface

- Contents

- PART I. STUDIES FOR THE FALL TERM: October–January

- PART II. STUDIES FOR THE SPRING TERM: February–May.

- PART III. STUDIES FOR THE SUMMER TERM: June–October.

- Outdoor Equipment

- Index