- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

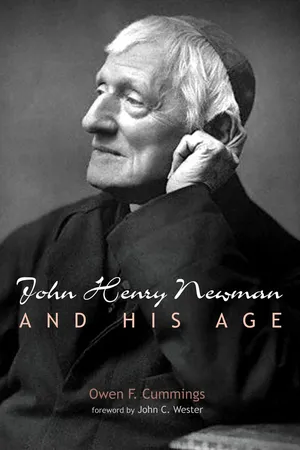

John Henry Newman and His Age

About this book

Many books exist devoted to the life, thought, and writings of Blessed John Henry Newman, the premier Catholic theologian in nineteenth-century England. His influence has been enormous, perhaps especially on Vatican II (1962-65). This book is a Newman primer, and not only a primer about Newman himself, but also about his time and place in church history. It attends to the papacy during his lifetime, his companions and friends, some of his peers at Oxford University, the First Vatican Council (1869-70), as well as some of his writing and theology. It should be especially helpful to an interested reader who has no particular background in nineteenth-century church history or in Newman himself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access John Henry Newman and His Age by Owen F. Cummings in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Newman’s Pope

Pope Pius IX (1846–78)

Pius was the first pope to identify himself wholeheartedly with ultramontanism, i.e., the tendency to centralize authority in church government and doctrine and the Holy See.

John Norman Davidson Kelly1

The pontificate of Pius IX . . . witnessed the victory of Ultramontanism over Gallicanism.

Ciaran O’Carroll2

From Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferreti to Pope Pius IX

For the first half of his life John Henry Newman was an Anglican, and for the second half a Roman Catholic. The nineteenth-century Catholicism to which he was drawn was marked by an increasing centralization on the papacy. This papal-centric emphasis is known as “ultramontanism,” a movement to which Newman found himself increasingly opposed. Pope Pius IX, who was pope during most of Newman’s life, and who was born in 1792, nine years before Newman, identified himself with ultramontanism, both consciously and unconsciously, and that identification spelled the end of Gallicanism—a kind of independence movement in the French Catholic Church—not only in its French form but in any kind of thinking that might be considered critical of the papacy. Pope Pius IX with his ultramontane perspective shaped the excessive papal-centrism of modern times, not only in respect of church governance but also in terms of ecclesiology. His predecessor, Pope Gregory XVI, a known strict conservative in virtually everything, viewed Cardinal Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti as something of an ecclesiastical liberal and said that even Mastai-Ferretti’s cats were liberals. Mastai-Ferretti was elected pope as Gregory’s successor in 1846, taking the name of Pius IX, and he served the church as pope until his death in 1878. It would be fair to say that he moved from a moderate liberalism to an extreme ultramontanism.

Although concerns were raised about his suspected epileptic seizures, he was ordained to the priesthood in 1819, and was sent by Pope Pius VII to Chile and Peru, accompanying Msgr. Giovanni Muzi, the apostolic delegate to those countries from 1823 until 1825. He was the first pope ever to have an experience of South America, although this was his only prolonged trip outside Italy, and arguably his informed awareness of social and political issues was too closely identified throughout his career with Italy and Europe, particularly Catholic Europe. The South American experience, however, stimulated his interest in the missions.3 After he returned from this extended visit to South America, he showed no particular interest in pursuing a papal diplomatic career.

He became Archbishop of Spoleto in 1827, was transferred to Imola in 1832, and was made a cardinal in 1840. While in Imola, Mastai-Ferretti was very popular with the poor, and his charitable activity constantly reduced him to straitened financial circumstances. “Far from courting an easy popularity amongst the propertied classes, or the higher clergy, he continued to show, even after he had received the red hat, an independence and liberality of outlook which often cost him the friendship of the larger landholders in his diocese as well as that of the senior government officials.”4 With this sense of commitment to the poor it is not difficult to understand his attitude to the reformers and progressives of his day, an attitude much less suspicious than many of his peers. He sided with the progressive cohort in the church and was an advocate for political reform. His views had been influenced by the work of the priest-philosopher and politician Vincenzo Gioberti (1801–52), and he was sympathetic to Gioberti’s liberalizing ideas, but E. E. Y. Hales is right to issue this caution: “It would be difficult to imagine anything more erroneous than the supposition that Pius was sailing with the wind in adopting liberal policies. He was not a great political thinker . . . but he was certainly not so foolish as to suppose that a liberal policy was going to be easy.”5 Pius was a moderate liberal, not an extremist reformer politically. And theologically? He would have had a basic awareness of theology—what Owen Chadwick calls “[theology] in outline,” but also a theology “without subtleties.”6

Pope Pius IX

In 1846, the somewhat liberalizing Mastai-Ferretti was elected Pope as Pope Pius IX. “The election of Count Giuseppe Mastai Ferretti as Pope Pius IX in the spring of 1846, after the draconian years of Gregory XVI’s rule, raised the sorts of hopes and expectations aroused in 1978 by the election of Karol Wojtyla after the fraught and depressing final years of Paul VI.”7 One of the first things he did as pope was to issue an amnesty for political refugees/revolutionaries from the Papal States—that section of Italy that fell under the jurisdiction of the popes—who had been living outside of Italy. They returned in their hundreds. This generous political gesture would create a climate expectant of rapid social and political change in the direction of a unified Italy. The dream of Italian unification had begun to grow towards the end of the eighteenth century, in part stimulated by the French Revolution and the Italian conquests of Napoleon Bonaparte.8 Italian unification was everywhere in the air, not only in political circles, so that, for example, it had become the passion of the immensely popular dramatist and poet Vittori Alfieri (1749–1803). Allied to these Italian nationalist aspirations were the constant criticisms of political commentators in Europe. “They grumbled that the clock of Europe had stopped in Rome, which was seen to combine feudal pretensions with Renaissance extravagance and whose rigidity and isolation led to stagnation, lamenting that while the world had changed, the church and its leaders had not. The papacy, and their perspective, represented a relic of the past, finding its persistence to the present ironic and unacceptable.”9 When it comes to the social and economic circumstances of the citizens of the Papal States, it has been pointed out that they were certainly no worse off than the working classes of European democracies, and in some respects were better off. There was no parallel in the Papal States, for example, to the Great Famine in Ireland (1845–52), largely mismanaged by the “enlightened” British government. However, Anti-papal sentiment at the time would never have acknowledged anything but what they took to be egregious mismanagement in papal government. “The Papal State was a benevolent theocracy. There was no longer a place in the Europe of 1864 for benevolent theocracies, and it may have been in the nature of things that the rising tide of the Risorgimento [the movement to unite Italy] should sweep this State away. But that is not a reason for stigmatizing Pio Nono’s [i.e., Pius IX’s] government as oppressive, or corrupt, or economically backward . . . . ”10 The overly negative opinions of the Papal States were, of course, well known to Pius IX. He could not have been unaware of them. However, there never was a time when Pius considered relinquishing the Papal States. He regarded their political independence as essential, indeed willed by God, ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Newman’s Pope

- Chapter 2: The Oxford Movement

- Chapter 3: John Henry Newman (1801–90)

- Chapter 4: In Newman’s Circle from Oxford

- Chapter 5: In Newman’s Circle from the Oratory

- Chapter 6: Newman’s Women!

- Chapter 7: Vatican I, 1869–70

- Chapter 8: Newman the Poet

- Chapter 9: Newman the Preacher

- Chapter 10: Looking Back

- Appendix: Going Further

- Bibliography