![]()

1

: How the City of Man Understands its Past

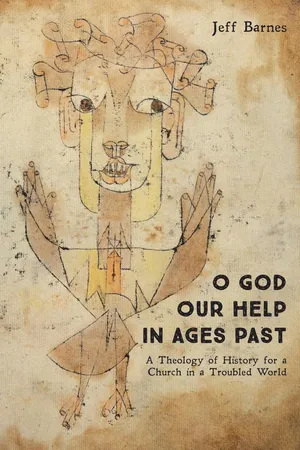

“A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

“Pilate said to him, ‘What is truth?’” (John 18:38)

Augustine, the great thinker of the early church, conceived of two powers vying for domination in the world. He termed the two forces, which coexist in the temporal span of human history, “the city of man” and “the city of God.” The former represents the kingdoms of this world as they rise and fall, never achieving the lasting glory for which they pine. The latter speaks of the heavenly city, the New Jerusalem, the culmination of the outworking of God’s deliverance of his elect. Both cities compete for our loyalty, and both demand our worship. As believers, we must learn to order our lives as residents of the heavenly city while we, at least for a time, inhabit the city of man: our hearts can only belong to one or the other.

Augustine’s bifurcated vision of the world can be seen in how human beings seek to uncover and understand their past. On the one hand, there is the city of man, which offers up understandings of history devoid of the divine. This is the angel of history imagined by social theorist Walter Benjamin, belayed as it were by the chaos laid at its feet as it pursues its vain resistance to the forces that would propel it into an equally chaotic future. The city of man’s understanding of the past posits a nameless, impersonal storm mistakenly called progress as the author tasked with writing the human story. On the other hand, there is a Christian theology of history that reads the events of the past through the lens of God’s sovereignty and his revelation of himself to mankind. In this vision, it is not the angel of history passively observing the human story unfold but rather a divine author who himself is committed to writing the story and revealing himself within it.

These two visions of the past are irreconcilable and are diametrically opposed to one another. The city of man’s understanding of the past posits history as an unordered chaos, an accidental lurching forward of humanity as it is beset by circumstances that are not only beyond its control, but beyond any control. Here, history is a tragedy and when, as Benjamin conceives it, we misscategorize the march of time as progress, also an irony. In contrast, a Christian theology of history looks at the past and, through the apparent chaos, discerns, even if it cannot fully comprehend, a force guiding the pattern of human existence. What appears to be storms preventing the angel of history from gaining a sense of its own meaning is in fact a divine hand scripting the events of history as they unfold throughout the ages. What seems on the surface to be chaos is actually order.

In this chapter, we will explore the dominant analytical framework employed by the city of man to understand its past. This paradigm, which has come to dominate the professional study of history (though it still has its passionate detractors), is termed “postmodernism.” It is this approach that dominates the history that most students encounter when taking courses at the university level. Further, the postmodern paradigm of history, like many other worldviews, has trickled from highbrow debates in academia into popular culture, becoming in the dominant way through which Americans perceive the world. Therefore, any meaningful discussion of a Christian theology of history, and of what Christians stand to gain through studying history, must begin by dissecting the opposite: a postmodern vision of the past, as represented by Benjamin’s angel.

Postmodernism and the Subjectivity of Truth

In order to define postmodernism as it relates to historical inquiry, we first must establish what the term is not. Postmodernism has become a buzzword in the academy and in popular discourse, which has led to some confusion about its meaning. Many within the church remain wary of the word and, in their attempt to denounce its implications for Christians, have misscategorized it. Further, the label postmodernism has been applied in other disciplines in ways that do not explicitly relate to the ideas we are going to be discussing here. As an example, postmodern art describes a particular style and epoch of artistic production and does not, for the most part, relate to the postmodern theory that is relevant for our discussion.

Categorizing postmodernism is problematic. Postmodernism is not a religion. Indeed, there are Christian postmodernists (although, as will be seen when we discuss the central philosophies of postmodernism, it will hopefully be apparent that this term is something of a contradiction), Muslim postmodernists, Jewish postmodernists, atheist postmodernists, and so on. Postmodernism is also not by definition an ideology. One can derive an ideology from postmodernism, but studying the past through a postmodern lens does not automatically assume such an ideology. At its heart, postmodernism is not even a philosophy, although there is such a thing as postmodern philosophy.

What, then, is postmodernism? For the purposes of our discussion, we will focus on postmodernism as an analytical schema that historians employ to understand the past. Other disciplines—including (but not limited to) literary studies, philosophy, and other members of the humanities—also make use of the analytical framework of postmodernism in their work. Think of postmodernism as a set of tools, any one of which can be pulled out when a historian is conducting research. The tool is used to provide a framework through which to make sense of the world. As we saw in the introduction, historians define history as change over time, yet they fervidly argue as to how that change occurred. Postmodernism provides a set of answers for historians seeking to address how change happens. Noted British historian Callum Brown has summarized this well: “By not being an ideology, postmodernism is a way of understanding knowledge. It is a way of understanding how humans gain knowledge from the world.” Postmodernism is one among many analytic frameworks employed by historians, but over the last several decades has become ascendant.

The fundamental axiom of postmodernism is that all truth is subjective and therefore the product of human construction. Nineteenth-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, considered by many to have laid the foundations of postmodern theory, summarized this belief, proffering that, “There are no facts in themselves. It is always necessary to begin by introducing a meaning in order that there can be a fact.” For postmodernism, the “fact” itself is of no consequence and indeed does not exist independently. Facts are products of a process of “meaning-making,” i.e., they come about as humans seek to articulate the world around them. This can be illustrated with an example. A postmodernist would make the claim that the floor beneath you does not exist. The designation “floor” is a product of human language and not a reality in and of itself. The “fact” of the floor, therefore, does not exist until we describe it with human vocabulary. Since the nuances of idioms vary from language to language, the floor exists differently as it is described by different persons in different languages in different historical situations. The designation “floor” exists only as we allow it to have semiotic meaning.

This approach is often incorrectly conflated with relativism, and the difference between relativism and postmodernism can be helpful in understanding how postmodernists conceive of the world. Relativism accepts different truths as equally valid. A relativist theology, for example, would maintain that there are multiple paths to God; no one religion can claim to be an absolute truth, and indeed multiple religions could simultaneously be true. Postmodernism avoids assessing the validity of truth altogether. Postmodernism posits that all that which we call “truth” is in fact only true because we have designated it as such. There is no one truth that is “true,” nor are multiple truths simultaneously “true.” Truth is in the eye of the beholder as defined by his or her specific location in time and space.

At this point, before we have even gotten into the weeds of postmodern theory or applied it to our understanding of the past, we can begin to see the contradictions between a postmodern worldview and a Christian one. Christianity posits the existence of an immutable truth that can be located in the divine. This truth, contrary to the postmodern assumption, exists; it is unchanging, unchallenged, and unconditioned by human interpretation. This truth finds its fullest expression in the person of Jesus Christ, God’s ultimate revelation of truth to the world. For the Christian, what constitutes truth is not up for debate. For the postmodernist, the very category of truth itself is fictive.

Postmodernism, Power, and the Historical Process

The whole of postmodern theory flows from the axiom that truth exists only to the extent that we create it and give it meaning. To understand the assumptions that flow from this, and then to see how these assumptions apply specifically to the historical discipline, we can begin by tracing the historical forces that shaped the development of postmodern theory. Postmodernism emerged as a challenge to the modernist worldview that preached a teleological view of history as an unmitigated march of progress. Modernists saw the advancements in science and industry in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the triumph of human intellect over the forces of nature and believed that humanity was on a permanent upward trajectory that would result in universal peace and prosperity. Within the church, modernist theologians saw the start of the twentieth century as the dawning of the prophesied millennium in which human achievement would bring the perfection of Christ’s kingdom to earth.

These idealistic views were shattered with the twin catastrophes of the world wars, which saw technology and nationalism—the idols of the modernist worldview—bring about the death of tens of millions for seemingly no cause. In the philosophical void that followed the world wars, intellectuals began to challenge the tenets of modernism together with traditional sources of power within society, such as religious and state institutions, and sought a new paradigm of knowledge. Simultaneously, the first half of the twentieth century saw the rise of social movements, such as the first wave of the feminist movement, which began to subvert the existing power structures cherished by modernism. Cultural works, such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, a compelling novel that belied the myth of Belgium’s supposedly “benevolent” colonialism in the Congo, brought these critiques to popular culture. With these challenges to the mechanisms of authority that modernists held dear and the devastation brought about by the world wars, postmodern theory came into being, though it would not be until the last two decades of the century that it would be embraced by historians.

This brief sketch outlines a fundamental aspect of postmodern theory. In addition to the axiomatic assumption that truth is subjective and that reality, as a result, is fundamentally unknowable, postmodern theory emphasizes the interplay between truth and power. French philosopher Michel Foucault (1926–1984), a towering figure in postmodern thought, articulated a theory of knowledge-power in which truth is created primarily as a mechanism of power. Foucault posited that societies joined different “facts” together to create what is termed a discourse, and that discourse, in turn, empowered certain groups within society. Foucault maintained that discourse is productive. Categories such as “homosexual,” he argued, were figments of the human imagination, a tool in a quest to establish a patriarchal regime. He stressed that prior to the late-nineteenth century, when much of the understandings we have today about sexuality began to be codified, homosexuals did not “exist.” He acknowledged that certainly there were men who had sexual relations with men, and women who had sexual relations with women, but that it was...