![]()

Chapter 1

What is Dementia?

Key messages

We are all individuals and dementia will affect us all differently. So, while we can look at core symptoms and behaviours that might be common in dementia, each individual will be affected and react in different ways. Each sufferer will retain a large element of their individuality and it is this which we need to latch on to and focus on in our interactions. There has been much poor care, the practitioners of which have seen sufferers merely as people with dementia for whom little can be done. What we need to try and do is to look beyond the label ‘dementia’ and try to get a sense of the individual beneath.

‘Dementia’ is a term used to describe a group of brain disorders which have a profound effect upon people’s lives and which share similar symptoms. There are different types, as outlined below, but whatever its form, dementia will usually impact upon memory and orientation to time, place and person. This is frightening enough, but the ability to think and communicate can be also severely eroded. Mood and behaviour can be affected alongside a decline in the skills and abilities of everyday life. The cognitive impairment is such that someone with dementia cannot learn new information. Dementia persists over time and is irreversible. Eventually the person affected may come to need full-time nursing care.

Alzheimer’s disease

The commonest form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, accounting for about 55 per cent of all dementia cases. The disease is progressive and irreversible; it causes shrinkage of brain tissue and the death of brain cells. We do not know what causes it but we do know that changes in brain structure are linked to abnormalities with chromosome 21. Typically, the onset of Alzheimer’s occurs when the person is in the mid-50s; however, it is not usually diagnosed until later when the effects are more noticeable. In the early stages of dementia the sufferer is often aware of their declining memory and cognitive functioning, which must be very frightening. Typically this insight leads to the sufferer denying problems and confabulating (making up stories or excuses to cover up the memory loss and errors); in this way it can be hard even for close family to pick up on the early signs. Women are more prone to Alzheimer’s disease simply because they tend to live longer.

Vascular dementia

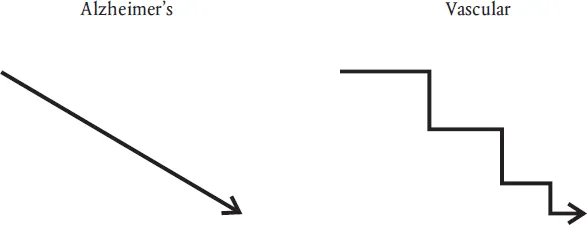

Vascular dementia is the second commonest form, caused by strokes in the brain where small blood vessels burst or become blocked. This cuts off the blood supply and therefore oxygen, causing the death of brain cells. It accounts for roughly 15 to 20 per cent of all dementia cases. The aspect of functioning that is affected depends on where the damage is in the brain, so there can be some aspects of mental functioning which are not affected. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease the onset is often sudden, and may be followed by further strokes and further deterioration. This is usually called ‘multi-infarct dementia’ and it has a step-like progression, a sudden decline being followed by a period of stability (see Figure 1.1). Usually with each further stroke there is further decline.

Figure 1.1Typical progression of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia

There may be several small unnoticed strokes which have the cumulative effect of damaging brain tissue sufficiently to cause dementia. Sufferers often have a high degree of insight in the early stages and this form of dementia is often accompanied by some physical loss of ability as a result of the stroke or strokes: typically, paralysis of limbs or loss of speech. Treatment is as for high blood pressure, which is factorial in causing strokes; thus, attention should be paid to diet and medication given to reduce blood pressure. Anti-coagulants can also be taken by sufferers to guard against the risk of a clot, and it is important that they stop smoking and reduce excessive alcohol intake, both of which are high risk factors for strokes.

Lewy body dementia

In Lewy body dementia small bodies grow in and destroy nerve cells in the brain; it accounts for around 15 to 20 per cent of all dementias. Typically, language, concentration and coordination are affected, with falls being a common occurrence. The loss of memory that is usually associated with a dementia is not so common among sufferers with Lewy body dementia and there is also some fluctuation between periods of lucidity and confusion. Auditory and visual hallucinations are common.

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

More commonly known as ‘Mad cow disease’, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, or CJD, has a rapid onset and causes rapid decline. It can occur at any age; it is especially tragic when it affects younger people. It is transmitted by eating beef infected with BSE. The symptoms occur some years after infection and the result is a full dementia. The epidemic of CJD which was at first expected failed to materialise and there are only some 200 cases worldwide; however, there may be more to come.

Pick’s disease

Pick’s disease is said to account for about five per cent of all dementias and women are twice as likely as men to suffer from it. It affects the frontal lobes of the brain and progresses slowly. It gives rise to profound personality changes which often manifest as disinhibited and inappropriate behaviour. This occurs alongside a deterioration in speech and eventual memory decline.

Depressive pseudo dementia

Often it can be very difficult to tell the early stages of dementia from depression, hence the name ‘pseudo dementia’. Both dementia and depression are characterised by poor concentration, poor memory, withdrawal and low scores on cognitive tests. In cases of dementia, however, the symptoms persist over time and do not respond to anti-depressant medication; the sufferer will often have a go at an activity and be unaware that they are doing it wrong. Sufferers from depression, on the other hand, will often undertake the activity slowly and give up due to lack of motivation.

Rarer dementias

People in the later stages of suffering the AIDS virus can also succumb to a dementia, as can some people in the latter stages of Parkinson’s disease. Sufferers of Down’s Syndrome can also develop a progressive form of dementia similar to Alzheimer’s in their middle age. Down’s Syndrome is associated with an extra chromosome 21, so this is an important area for further research. Huntington’s Chorea is a rare degenerative brain disorder which is inherited and affects half of all offspring. Tragically it is not usually noticed until the sufferer has reached their early 30s by which time most people have started a family. It is characterised by incapacitating jerking movements of the limbs and is usually accompanied by a form of dementia. Long-term misuse of alcohol can cause a dementia known as Korsakov’s Syndrome which is typified by an extremely short memory span. It is caused by a deficiency of the B vitamin thiamine.

Acute confusional state and other causes

Chest and urine infections can cause confusional states which mimic dementia but are all treatable with antibiotics. Constipation is also one of the biggest causes of confusion in older people, but is often overlooked. Other common reasons for confusion are pain, the side effects of medication, poor fluid intake, alcohol, brain tumour, grief and depression. This list is not exhaustive and it demonstrates the need for a thorough initial screening and assessment process.

Reminder

Dementia is not a part of the normal ageing process. There is some cognitive and intellectual decline which can be put down to normal ageing, but dementia is a terminal illness that has a far greater impact upon the individual. Accurate estimates that one in five people over 80 will suffer dementia can make old age seem like a depressing scenario and if we work with older people with dementia we can get a jaundiced and negative view of the future. Thus we should recognise the fact that 80 per cent of the over 80s will not suffer dementia.

Further reading and references

Cheston, R. and Bender, M. (1999) Understanding Dementia: The Man with the Worried Eyes. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Chapter 2, ‘The present formulation of dementia’, gives a good explanation of all the ways of looking at dementia and explaining it, alongside details of the variations and the possible risk factors.

Holden, U. and Stokes, G. (2002) ‘The “Dementias”.’ In G. Stokes and F. Goudie (eds), The Essential Dementia Care Handbook. Bicester: Speechmark.

This is an excellent book and this chapter (Chapter 2) gives a good overview of the various forms of dementia.

Stokes, G. and Goudie, E. (1990) Working with Dementia. Bicester: Winslow Press.

![]()

Chapter 2

History of Dementia and Dementia Care

Key message

Over 20 per cent of the over-80s will suffer some form of dementia and most dementia sufferers are being cared for in the community by their families.

The word ‘dementia’ has been around for quite some time and comes from the Latin demens which literally means ‘without mind’. The Greeks, including Plato, recognised it as an abnormal condition of old age. By the eighteenth century it was becoming medically recognised as ‘abolition of the reasoning faculty’, according to a French scientific encyclopaedia of 1765 (Berrios 1994). However, it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that dementia of early onset became recognised as a specific medical entity. It was then associated with cognitive impairment, memory decline and a decline in social functioning.

For many the workhouse was the only care option until the Victorians built the large asylums. In 1907 Dr Alois Alzheimer published a paper identifying a cluster of symptoms of dementia. These included reduced comprehension and memory, disorientation, unpredictable behaviour and difficulties with communication. Thus Alzheimer’s disease was born. There was then a period of very little research into dementia and care for sufferers was largely ignored. If not cared for at home many dementia sufferers were cared for in long-stay ‘psycho-geriatric’ wards. With the decline of NHS long-term care in the 1980s, institutional care of dementia is now largely a function of private residential and nursing homes. The issue of responsibility for long-term care and dementia care generally has long been a bone of contention between health and social services. There is still much debate as to whether caring for a dementia sufferer is a nursing or a social task. In Scotland long-term care for dementia is free, as it is seen as a nursing task. However, in the rest of the UK politicians regard the care as being primarily social in nature.

In the 1970s pre-senile dementia such as Alzheimer’s was largely regarded as untreatable and was rarely acted upon or brought to the attention of specialist services, of which there were few, and there had been very little research into the disease. Cheston and Bender (1999) point out that during the 1970s there was a realisation that increases in life expectancy would result in greater numbers of dementia sufferers. In the UK in 1930 the average life expectancies were 59 years for men and 68 for women. By 1970 these had risen to 63 and 74. This had huge implications for health and social policy and it is because of the large numbers of people involved ...