- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

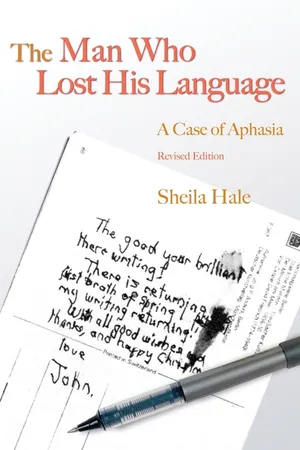

The Man who Lost His Language is a unique exploration of aphasia - losing the ability to use or comprehend words - as well as of the resilience of love.

When Sir John Hale suffered a stroke that left him unable to walk, write or speak, his wife, Shelia, followed every available medical trail seeking knowledge of his condition and how he might be restored to health. This revised edition of a classic book includes an additional chapter detailing the latest developments in science and medicine since the first edition was published.

This personal account of one couple's experience will be of interest to all those who want to know more about aphasia and related conditions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Man Who Lost his Language by Sheila Hale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Neuropsychologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

John

I confess I do not believe in time. I like to fold my magic carpet, after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another. Let visitors trip. And the highest enjoyment of timelessness – in a landscape selected at random – is when I stand among rare butterflies and their food plants. This is ecstasy and behind the ecstasy is something else, which is hard to explain. It is like a momentary vacuum into which rushes all that I love. A sense of oneness with sun and stone. A thrill of gratitude to whom it may concern – to the contrapuntal genius of human fate or to tender ghosts humouring a lucky mortal.

Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisited

I am studying a photograph of John taken in 1927 or 1928 when he was four or five. It’s one I’ve always liked and kept where I could glance at it from time to time. These days I examine it more closely, searching for clues to the way he is now. I know John at the other end of his life as well as one person can know another. But I want more. I want to know what it is like to be John.

It is high summer in an English garden. John has been persuaded to settle on a rug on the lawn with his two older sisters, Joan and Polly. Polly, the tallest child, is sitting with a large Pekinese sprawled on her lap. Joan, the eldest, has been shelling peas into a colander, which she has set aside for the photograph. The two girls are laughing for the camera. John is not laughing. He is quietly amused, inquisitive, no doubt planning some adventure; possibly already a bit of a ham? He is perched neatly on his heels, wearing shorts and a cotton shirt buttoned up to his neck, hands resting palm to palm between his bare thighs, self-contained, ready to go. He is a very pretty little boy, his thick hair dappled with patches of reflected sunlight. The hair, although you can’t see it in the black-and-white photograph, is a colour which John later described to me (not altogether ironically) as a ravishing shade of burnished copper. When it was first cut his mother wrapped a lock of it in tissue paper and preserved it in an envelope, labelled with purple ink in her flamboyant handwriting: ‘First cut of my darling John’s hair aged 1 year 8 months.’ Below this inscription there is another note, in purple ink: ‘Another cutting taken on Sept 6, aged 9. Colour hasn’t changed. Like two tongues of fire.’

John’s father was a country doctor who knew all the music-hall songs and charged his patients what they could afford to pay. Some expressed their gratitude with gifts of family heirlooms – bits of antique porcelain or cut glass; the maple-framed samplers which now hang in our kitchen. He was the kind of doctor who visited the sick at any time of day or night, and he died, possibly of overwork, when John was fifteen.

John’s mother was a nurse but she retired when John was born to devote herself to her only son. Her other interests were amateur theatricals, spiritualism and the philosophy of Rudolph Steiner. But it was John who was the centre of his mother’s mildly eccentric universe. And her unconditional adoration of the late, unexpected golden boy seems to have been shared by Polly and Joan, already eight and ten when John was born, as well as by all the aunts, uncles and family servants who peopled the stories about his childhood that John was to tell his children at bedtime and after lunch on rainy Saturday afternoons. Some of the stories were surreal, some mock-spooky; many involved elaborate practical jokes. The stories always ended happily with the family comfortably reunited over a delicious tea in the large, safe house in Kent, surrounded by cherry and apple orchards that even a charitable doctor could afford during the depression.

It was in this gentle, bourgeois environment that John developed his compulsion to write. Judging from the prodigious volume of his juvenilia, which his mother returned to him shortly before she died, John, from the age of eight, must have spent many hours of each day writing. He wrote poems, plays, stories, accounts of extraordinary and ordinary days in his life. He wrote a poem about his appendix operation; several stories about his uncle’s false nose (the real one having been shot off in the trenches), which was kept in place by an elastic band around his head. He wrote about his favourite puddings (trifle and spotted dick) and about the colours and shapes which were projected on his inner eyelids when he closed them. His letters home from school tended to be either in verse, or to be plays starring ‘our lissom, auburn-haired hero, John’. His notes about butterflies and birds, their habits, eggs and calls, are accompanied by rough, expressive sketches, with arrows pointing to those he says he wishes he could draw better.

The copy of T. A. Coward’s classic The Birds of the British Isles and their Eggs1 which John won at his school in 1934 as first prize in natural history is, with the photograph in the sunlit garden, one of the talismans I keep on my desk, as though it might act as a passport to the mind of the man I know so well but not well enough. Although T. A. Coward is admired even today by ornithologists for his scientific methods of observation, he could not refrain from anthropomorphic moral judgements, directed particularly against bullies and cowards – two classes of people John has always scorned. The golden eagle, for example, ‘in romance is fierce, terrible, and a robber of infants; in reality it is a large, powerful, magnificent bird with a cowardly vulturine character’.

The illustrations in John’s 1933 edition are sparse and feeble. You have to peer very hard at the black-and-white photograph of a tree trunk to distinguish the tiny black-and-white tree sparrow ‘at nest’ on a hole in the bark. But T. A. Coward’s descriptive power does the work that colour photographs and television have now made unnecessary. I turn to the section on the peregrine falcon, Falco peregrinus Turnstall, ‘the largest and most common of our resident falcons … commoner, especially around our rocky coasts, than is usually supposed’. The gripping description that covers the following pages is written in a prose that must have influenced John’s own mature style:

There is a dash, neatness and finish in the flight of the Peregrine which is purely its own. The wings move rapidly, beating the air for a few moments, and are then held steady in a bow whilst the bird glides forward, sometimes rolling slightly from side to side … Near the eyrie the birds have look-outs, some jutting rocks or pinnacles on the cliff face … On the cliff-top, near the eyrie, are the shambles, scattered litter of blood-stained feathers and the rejected remnants of many a victim … Immediately after giving the fatal blow with the hind claw the destroyer shoots upward, descending later to enjoy its meal. The rush of a swooping Peregrine when heard at close quarters is like the sound of a rocket … No nest is made; the two to four richly coloured orange-red or deep brown eggs are placed in a rough hollow scraped on some ledge of a steep crag or cliff.

In the summer of 1937 when John was thirteen he volunteered to take part in a Royal Air Force mission to subvert the mating activities of peregrine falcons on the cliffs of Wales where they were endangering national security by disturbing radar signals. It was John’s job to remove the eggs from their ledges and crags. He was lowered by rope down the cliff face, equipped with a soft bag in which he placed, one at a time, the richly coloured eggs so they could be transported to a safe but less intrusive hatching ground.

When John and I met twenty-seven years later, he often talked about his peregrine summer. And two months before our son JJ (John Justin) was born he took me to Wales on a walking tour of the cliffs and made love to me on the one he remembered as the site of his egg-rescuing adventures. Oddly, there is no evidence that he wrote at the time about the experience he was to remember so vividly for the rest of his life. His letters home from school that autumn are mostly about rugby, which he played as scrum half. Everything else is going ‘pretty well’, but it is rugger that makes the prose light up. Then he is in the school infirmary having hurt his knee in a rugger game.

The bruise developed into osteomyelitis, a bone-wasting infection that is still serious, even now when it can be treated with antibiotics. Doctors have told me that osteomyelitis is so painful that they are sometimes prepared to relieve it with potentially addictive amounts of morphine, which can lead to an extended period in hospital while the patient dries out. John was in a wheelchair for eighteen months. He nearly lost the leg, at least according to Polly, who believes she may have saved it with her powers as a faith healer. The school doctor gave him nothing stronger than aspirin. Perhaps his father would have been more indulgent; but he was far away, bedridden by what proved to be his last illness. Polly says that their mother, who took a flat near the school, was often hysterical – more, it seems, about John than her husband – but that everyone else, especially John, bore his suffering bravely: gritted teeth, no crying.

Many years later, when I touched the scar, in bed with John for the first time, he told me about how much he had enjoyed reading Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle in his wheelchair, and about the fun of watching the leeches suck the pus from his infected knee. He didn’t mention pain or frustration, and I didn’t think to ask. At forty-one, fifteen years older than me, his auburn hair now streaked with silver as though by a good hairdresser, he seemed to me impossibly glamorous, and impossibly invulnerable.

By 1939 John was up and walking again, well enough to take part in army drills. His attitude to war (which was to be one of his chief interests as a mature historian) was already evident. Marching in the middle of a large company of officer cadets he would occasionally swing the same arm as his leg. The RSM overlooking his body of soldiers was puzzled to see that the symmetry was broken, but could not identify the problem. The young professional schoolmasters had gone off to fight in the war. They were replaced by elderly volunteers who were only too happy to depart from the syllabus and share their particular intellectual passions with John. One introduced him to French and Spanish literature, another to the social theories of Shaw and Ruskin, a third to art history, which was not then a subject formally taught in schools or universities. His battered brown-paper editions of French and Spanish novels, plays, poetry and memoirs, pages all cut, are on the shelves of the library that lines the walls of our tall old house by the river; as is the two-volume edition of the prefaces and complete plays of George Bernard Shaw, which John won as a school essay prize. We once had the Travellers’ Edition, Ruskin’s own abridged version of The Stones of Venice. That has disappeared, perhaps worn out from too many trips to Venice or loaned to some student.

His favourite reading at sixteen was J. A. Crowe and G. B. Cavalcaselle’s History of Painting in Italy. His three-volume 1908 edition edited by Edward Hutton is still in good condition, possibly because nobody, except John in nostalgic moments, has looked at it since. I have to stretch my imagination to guess what it can have been about these formidably dreary-looking books that appealed so strongly to an adolescent boy. The closely printed pages are heavy with detailed descriptions of works of art John had never seen and closely argued attributions, qualified by footnotes, to artists whose names he could never have previously encountered. The mean little black-and-white photographs of works of art are even less inspiring than the birds in T. A. Coward. But they seem to have had a power for John, as for other art-loving members of his generation, that is lacking in the lavish colour reproductions and educational weekend breaks in ‘art cities’ that are widely available today.

Sometimes I gaze at John gazing at some work of art in a gallery or church. He can easily spend an hour or more standing absolutely still in front of a single work of art. I see a man in a state of self-transcending ecstasy that is achieved only rarely, if ever, by those of us who grew up later, force-fed with clamorous technicolor images of everything from toothpaste to high art. He is old and lame, but, at such moments, I envy him. I am overwhelmed by the recurring desire to share his ecstatic self-forgetfulness. If I interrupt him with questions about the picture that is absorbing him he points, waves his stick, blows kisses at it; and puts his finger over his mouth as though he were listening to something.

He didn’t get to see the originals of the Italian paintings in Crowe and Cavalcaselle until 1946 when he made his first pilgrimage to Florence, travelling across war-torn Europe on his motorbike, with a girl on the back. He abandoned her for ever in the Piazza del Duomo when she failed to share his rapturous enthusiasm for the Baptistery. His first major book,2 England and the Italian Renaissance, a pioneering investigation of the history of the English taste for Italy, is an attempt to explain to himself the impact Italy made on him. Its preface begins with an indirect and rather generalized apology t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Of Related Interest

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1. John

- Part I: The Stroke

- Part II: Aphasia

- Part III: John’s Aphasia

- Afterword

- Postscript to the Revised Edition

- Useful Addresses

- Notes

- Bibliography