![]()

Chapter 1

“If You Turned into a Monster”

“Draw a picture of what you would look like if you turned into a monster,” I tell the seven-year-old sitting stiffly before me. It is our first session together so we are both feeling a bit awkward. She looks wide-eyed with disbelief at my request. Her parents have most likely told her that she is coming to talk to me about her problems. I try again. “Imagine you have drunk a magic potion and your body is changing into that of a monster. Really try and imagine that it’s happening to you. Then draw what you look like.” She realizes I am quite serious and with that the little girl smiles and proceeds to draw a spectacular beast with bulging eyes, an enormous mouth and two huge fangs dripping with blood. When she finishes she is obviously quite pleased with the outcome. “Does it have a name?” I inquire. Without any hesitation she christens it “Mouth.” “And what does your monster do that makes it so monstrous?” I ask. Again, without hesitation and even with a touch of confidence she exclaims, “It eats everyone.”

When I first meet a child with whom I am going to be working therapeutically, I usually ask the child to draw himself or herself as a monster. I do so for a variety of reasons. Monsters are after all our first creative acts as humans. From early on we dream them and imagine them. They dwell under our beds or behind our bedroom doors. They peek in through our windows. They are often right on the edge of our developing consciousness, part instinctual urge and part deity. We wake our parents in the middle of the night because of them, and our parents try ineffectually to dispel them by saying things like “There’s no such thing as monsters” or “It was just a dream.” But all their reassurances and dismissals are to no avail, for as young children we know that these first creative acts of ours, no matter how much we dislike them, do exist and are “ours.” They belong to us and somehow they are us. If only our parents would express an interest in these beasts, as well as trying to comfort us. If only they asked “What did it look like tonight?” their children would not feel so alone with the power that these monsters personify. But we as parents have lost direct access to our own monsters. We too fear these beasts. We doubt the truth of our dreams.

These first creative acts of ours are a mixture of instincts, emotion and also an early experience of deity. They are the child’s efforts at negotiating the bigness of life, both within themselves and around them, in all its ramifications. Children almost always respond to my request with disbelief and then relief. Even the more timid of children such as the above child are eager to speak through this monstrous form. They know this, more than they consciously know themselves.

Children come to therapy with monstrous feelings – monstrous grief, monstrous rage, monstrous longing – to name a few. These feelings are unacceptable, unfaceable, and unmanageable to themselves, as well as to the world around them. The invitation to draw themselves as a monster is an immediate acknowledgment of these feelings as fact, and an acceptance of their existence and legitimacy. Children receive this communication on an intuitive level, the primary level on which deep communication takes place with children. I also, in a sense, form a potential allegiance with this monster, symbol and composite of so much. By giving it permission to exist as a part of our relationship, I immediately dissipate some of the negative power that it possesses.

Many things begin to happen as a result of this allegiance. The drawing itself, what it actually expresses and, even more important, how the child experiences it, can point the way towards health. The above child’s monster, with its overemphasized fanged mouth, could be seen to indicate a need and a desire to sink one’s teeth into life. It would suggest that a great deal of anger would be released along the way. The ease with which she drew it tells me that beneath her shy exterior she is a real dynamo. Perhaps it is this very thwarted dynamism that has turned into the list of symptoms she has come to therapy with. The act of expressing this thwarted energy via such a drawing is a significant step in the process of redirecting it. Part of the child’s self, which has been repressed or never developed, can begin to emerge and evolve simply by making the statement which the drawing makes, that is, “This is me,” or “This is how I feel.”

The variety of monster drawings presented to me is astounding, from the ridiculous to the sublime, but almost all with an edge of humor. Even the most violent “self” monster drawings have a humorous twist. I think this says much about our potential as humans, that this paradoxical ability to embrace all aspects of the human experience in one form is still present in young children. When do we lose this I wonder?

One of the first children I ever worked with over 30 years ago brought me a book of Eskimo tales as a gift. The first story in the book was called “The Giant Bear.” The book has long since disappeared from my collection and I have been unable to find the story reprinted elsewhere. Yet it is quite vivid in my mind.

Once a giant bear was ravaging the countryside, eating everyone it came upon. The people of the area were terrified, but one young boy set out to find the bear. Everywhere he went in his search for the giant bear people told him, “Are you crazy? Run for your life!” Yet he continued on his way and eventually came upon the bear. He rushed up to it and allowed himself to be eaten. The monster swallowed him in one gulp. Once inside the bear’s belly, the boy took out his knife. He carved a door in the bear’s stomach and leapt out, killing the bear, of course. Then he freed all those who had been eaten and called everyone together to help him butcher the bear. And there was bear meat for many months to come. That’s the way it goes; monster one minute and food the next.

Our basic response to a story such as this is on a gut level. We feel what it means. And it is precisely on this gut, feeling level that psychotherapy with children takes place. It is from here that the child speaks and it’s from the same place in ourselves that we must listen. We rarely need to analyze or interpret. In fact, to do so often interferes with the process that is taking place.

It is the use of metaphor and allegory that makes stories such as this so profound, and it is this same metaphoric language which children speak in every play configuration they make, be it drawings, clay figures, sandplay or stories. Our task is not to translate but to accept it as it is. Its richness exists in its allusion to, its insinuation.

The huge mouth monster created by the seven-year-old of herself is experienced as “of her self.” Thereby the regenerative power the monster possesses is also experienced as “of the self.”

Literature abounds with examples of transformation involving monsters. In Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, the child Max, after being punished by his mother for being too wild, travels in his imagination to a land of monsters where he is king. He roars and gnashes his teeth with them until he has vented his frustration. Then he sails back home, his integrity intact (Sendak 1963).

In C.S. Lewis’s Voyage of the Dawntreader, there is a selfish, unloved, and unlovable child named Eustace, who at one point puts on a magic bracelet and is transformed into a dragon. In this monstrous state he experiences how much like a monster he really is. Eventually he is healed, the dragon skin and the armor of his defenses peeled off, layer by layer. In the end he appears in his original state, vulnerable but human (Lewis 1988).

In the classic French fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast” a prince has been enchanted and changed into a hideous beast. The character Beauty eventually breaks the spell by loving him despite his beastliness, by recognizing the deeper beauty within him. The beast is transformed only by a total acceptance of it (Perrault 1961). The main characters in all of these stories are transformed too by their encounters with the beasts. They become more mature and more human.

These stories, and many others like them, move us because they describe a transformation in which what is vital in the person is affirmed, freed or reborn. We also relate to them, especially the child or the child in us, because somehow we know that transformation only happens by accepting the monster.

In working with children we must help provoke this type of transformation in what is a paradoxical manner. The therapist hands out the magic bracelet and then helps peel off the skin. He shows the child where the Giant Bear is and then helps with the butchering. He accompanies the monsters dancing in the land of the wild things and then pushes the child’s boat off for home. He makes the realm of the Beast less terrifying, so that the child can make peace with the part of himself or herself that dwells there. Through a combination of humor and great seriousness he plays the role of guide and assistant, yet steps out of the way quickly so as not to interfere with the forces of play.

For the most part, the monsters that children draw in therapy have nothing in common with the monsters with which television and movies bombard us. Adults whose aim, aside from making money, is to horrify us, create these monsters. That these monsters are compelling to children has to do with the feelings of horror they evoke. In a lecture by Alexander Lowen entitled “Horror: The Face of Unreality” he asserts:

I have often wondered why children are fascinated by horror movies. … I have thought that it represented their need to overcome the sense of horror enough to be able to function in a world that contained much horror. But the introduction of horror via movies does not help us cope with horror. It blinds us to horror by making us assume that it is a natural part of life. We learn to accept the horror, not reject it, and we become victims of horror. (Lowen 1972, p.1)

The media uses monstrous images to create numbness and disassociation. It hooks us with its horrific images that serve no therapeutic value, in fact quite the opposite. This aspect is not usually present in the monsters that children draw for me. The media, by bombarding children with adult-generated images of horror, does real damage to the child’s developing psyche. I find that nowadays I sometimes have to help children reach into themselves through a layer of mechanized and horror-induced numbness. But rather quickly in most cases the real monsters emerge, the ancient ones! These ancient ones arise from deep within and far from disconnecting us from ourselves they open doors or keep a pathway open to a deeper connection.

With most children, the spontaneous monsters which they create literally out of themselves are life affirming. Their grotesqueness, and any violence they describe, has potentially a healing function. The point is not to horrify but to rectify, to change a situation that is negatively energized, and that threatens the child’s integrity. We may begin to understand this transformative process better by looking at one child’s monsters in particular.

The key to the heart

Eli was a six-year-old brought for therapy with a long list of symptoms. These included thumb sucking, wetting and soiling his pants, self-stimulation and social withdrawal. Due to this latter, Eli had no friends. He got along well with adults and possessed a rather adult vocabulary, despite all the infantile symptoms. This dichotomy between his adult-like demeanor and his infant-like symptoms was significant.

Some of the symptoms from infancy had only partially disappeared, at which point they were normal behaviors. Still others were part of an overall regression, triggered by the hospitalization of Eli’s father for severe alcoholism. His father had been battling alcoholism unsuccessfully for years, and had entered rehabilitation programs periodically only to fail each time. Eli’s father was like a child himself, perhaps explaining Eli’s need to act grown-up.

Eli’s mother, though a more stable and mature individual, felt overwhelmed by the responsibility of being the sole breadwinner and parent. She also felt a sense of guilt and hopelessness about her weak husband, rather than anger, which would have been more appropriate and empowering, but “not nice.” Eli, for both his parents’ sakes and with them as role models, was overly obedient and helpful. Yet his body was expressing his deeper feelings and his level of functioning was deteriorating rapidly.

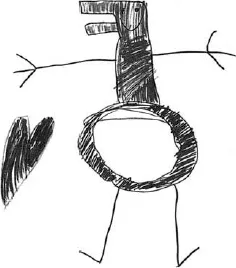

At our first meeting Eli entered the play space eager to please me, yet also eager to play. His body was very small for his age and his head was disproportionately large. He looked very sad and worried, with the weight of the world on his tiny shoulders. Eli sat down and drew a monster at my request. The monster he drew was actually a large key with human features. It had no name and no attributes. After exploring, with satisfaction, the other possibilities in the play setting, he came back to the drawing and added a small heart next to the key. “It’s the key to the heart,” he said simply. “Take care of it!” (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The “key to the heart” monster

After handing me the heart-key monster drawing, Eli used my office bathroom. This was the first time he had used a toilet rather than his pants in many weeks. As is often the case, there was a direct body connection in his imaginal play. Eli was saying something so important in handing me his monster, yet neither of us needed to know exactly what was being said. What was important is that it was.

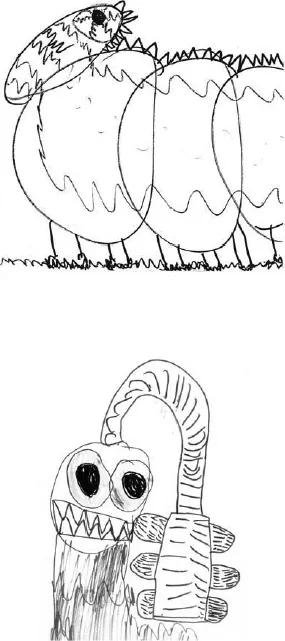

In subsequent sessions, Eli began each time with a monster drawing, or sometimes he leapt up in the middle of his play and spontaneously began to draw a monster. These monsters were all very alive. Huge, slithering, coiling snake-like creatures, they covered the paper and eventually my walls. Some had several heads and all were exploding with energy. They all had elaborate names. Many of them evolved or metamorphosed while he was drawing them, and the best way to describe the series was “matter transforming itself.” This changing, volatile energy was actually palpable in the room as Eli worked on his drawings (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Eli’s drawings: matter transforming itself

The remainder of each session entailed his embodying and using this newly formed energy in a variety of ways. Fighting with me with foam “encounter bats” was a means of experiencing and directing his emerging aggression at someone who could accept it and yet give it limits. Building huge towers out of blocks and smashing them down gave vent to both the creative and destructive aspects of this aggression. As is often the case with children like Eli, he began by being concerned with making these towers correctly. This evolved into his destroying them and then eventually he came back to creating them for their own sake. These later block assemblages were much more interesting and dynamic.

Most of Eli’s symptoms disappeared very quickly as the raw energy, expressed by his monsters, went through its various representation...