![]()

1

What is the Professional Therapeutic Relationship?

A woman walks through a field, a garden, a park. She’s in a hurry on her way to work, she’s distracted by a message on her phone, she’s weeping because her lover has left, she’s running to collect her child, she’s running away from her past. She walks and sees nothing.

A woman walks slowly though a field, a garden, a park. The air is sharp and tinged with leaves burning, the air is warm and rose scented, the air is moist and smells of earth after rain. The grass is neatly mowed, the grass is long and yellowing and waves in the breeze, the grass is fresh green dotted with daisies. The woman names the flowers to herself: buttercup, cow parsley, ragged robin, begonia, petunia, busy lizzie. She walks and is mindful.

A woman walks through a field, a garden, a park. Every leaf, blade of grass and petal is vibrating with life, colours intensely vivid, the air dancing with spirits and singing. Energy streams through her and around her, the woman and the plants and the earth, connected in a living, pulsing web. For a moment, the woman walks and the veil between the worlds is lifted.

There are many ways of being in the world. There are many ways of relating to our fellow human beings. The more we can be present and mindful and aware, the more richness and potential there is to touch another’s soul and to let ourselves be touched. If you’ve ever been involved in an intense group activity you might have come across that sense of really meeting the others who were on the journey with you. We are introduced to someone at a party, we chat for five minutes and then say ‘Nice to meet you’. But we didn’t, not really, meet that person, or let ourselves be met, not our raw, strange, wonderful and quite unique selves. We let others see the version that’s been modified for public consumption. In the descriptions above, the woman’s awareness of her surroundings ranged from nearly oblivious to totally interactional. In a similar way, we, as complementary health professionals, can be ignorant of or attentive to the framework within which we relate to the people we work with.

Maybe it helps to define the purpose of this book if we consider the different types of relationship that can exist between two people, relationships that we might define as therapeutic. Let’s begin by thinking about the professional and the therapeutic aspects. At its most basic, the professional relationship is one in which one person is qualified to offer particular services to another, and is remunerated for this in some way. There is a clear contractual element, and the relationship takes place within a specific context such as an office, a treatment room, a website or wherever the professional works. It is time limited, so when the services are no longer required, the professional relationship ends. This description applies to lawyers, homeopaths, doctors, plumbers, architects, garage mechanics and many others.

The therapeutic relationship exists when one person offers help, support or caring to another person in need. At its most informal level, a therapeutic relationship exists when a mother washes and puts a plaster on her child’s grazed knee, or when someone offers a shoulder massage to a stressed friend, or an elderly person who’s fallen in the street is helped by a passer by. The helper may or may not be qualified to do so, the relationship may be a familial one or between two strangers, and the services offered may not be reciprocated. There is no contract.

A professional therapeutic relationship exists whenever two (or more, if the one who needs healing is a child or an adult needing an advocate or interpreter) people meet, and one has skills and expertise which the other wants to alleviate suffering, or, for many people who consult CAM practitioners, to maintain levels of health and well being. The relationship is contractual, governed by legal, professional and ethical guidelines and the practitioner is remunerated for her services. The professional therapeutic relationship takes place within a particular setting such as a treatment room, a clinic, a hospital, a health centre or the client’s own home. The professional therapeutic relationship ends when the services are no longer required, but there may be exceptions to this, which we’ll consider later.

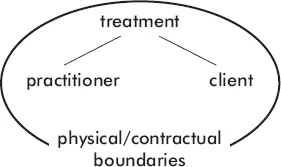

Therapeutic relationship as treatment only

What happens within the professional therapeutic relationship? At its most basic, there’s the setting, an exchange of money, a professional, a client and the treatment. In some contexts the focus is entirely on the treatment. If you have been to Turkey you may, like me, have been to a Turkish bath or hammam and had the wonderful experience of lying on a marble slab, covered with rose-scented lather, pummelled and rinsed down. For me, this was definitely a therapeutic experience and I felt great afterwards, and it was also a professional one (I asked – the masseur was qualified) but the interaction between us was minimal, limited to gestures on his part – come here, lie down, turn over, we’re finished. I wouldn’t have recognised him if I’d passed him in the street an hour later. Another therapeutic experience I’ve had which focused entirely on the treatment was using flotation tanks. There was a person involved, who asked if I was pregnant, had high blood pressure or was taking medication, showed me what to do, and waited somewhere outside to let me out if I pushed the panic button and who turned off the music and turned on the lights when my session was over. My body felt soft and relaxed, as if I’d had a massage without being touched. The therapeutic relationship was minimal but I had had a therapeutic treatment.

An image of this level of professional therapeutic relationship would look like this:

Figure 1.1 Therapeutic relationship as treatment only

Therapeutic relationship with interpersonal skills

To move on to the next level of complexity, we have the sort of relationship that is professional and therapeutic, and there is a treatment involving the skills and expertise of the practitioner, and there is something more that has a definite effect on the outcome. This additional factor is the relationship between the practitioner and client. When I taught professional massage training, there was an exercise I used to demonstrate the importance of the practitioner’s attitude and behaviour during an initial consultation. I’d role-play with a willing accomplice how not to do a good consultation. It would go something like this:

And then, when the laughing stopped, we’d all work out where this ‘practitioner’ was going wrong and, from this, identify elements of good practice in establishing a working relationship with a client. The list would look like this:

•clear boundaries between personal and professional

•being able to make a clear contract with the client

•being prepared

•good listening skills

•communicating clearly and simply

•empathy

•focusing on the client

•and, in the case of the ‘practitioner’ above, being polite.

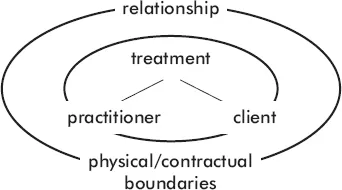

So now we have a professional therapeutic relationship where the treatment and the relationship both have an impact on the eventual outcome. A visual image would look like this:

Figure 1.2 Therapeutic relationship as treatment influenced by practitioner – client relationship contained within professional boundaries

Some people are very good at relating to others, and others struggle. Some can talk with ease, others are pretty inarticulate. Some are confident, others are shy. For some, good listening is second nature while others can’t recall what someone said two minutes ago. Some attune to others’ emotional states without even knowing that they are doing it, while others do anything to avoid feelings. But whatever a person’s strengths and weaknesses in this area, interpersonal skills can be improved. We can learn to communicate simply, or to listen well, or to keep good boundaries. The skills involved in establishing and maintaining good practitioner-client relationships are relevant to practitioners of all kinds of complementary therapies, from Reiki to Rolfing, homeopathy to herbalism, iridology to Indian head massage. And if interpersonal skills are as important as the treatment, why not do everything we can to use them consciously and improve our weaknesses?

Self awareness is another factor that helps us to relate smoothly to others. For example, it helps to be aware of our beliefs and accompanying feelings about people who are different from us. It helps to have explored the reasons why we came into a helping profession, so that we are clear about our hidden as well as our conscious motivation for being a complementary therapist. Our families are our first teachers when it comes to interpersonal relating and, however hard they tried, there were bound to have been mistakes. It helps to have explored the rules you internalised as a child and to have an awareness of problematic relationships and how that affected you.

And for most practitioners, most of the time, with most clients, good interpersonal skills and self awareness are sufficient. But there are occasions when difficulties arise, we feel out of our depth, are puzzled by client’s reactions, are puzzled by our own feelings and just can’t make out what is going on. Have you ever looked at your client list for the day and felt dread at seeing someone’s name, even though you know he is a perfectly pleasant person? Or felt unaccountably hungry after seeing another client even though you just had lunch? Or experienced fuzziness and found it hard to think clearly when talking to another? This brings us to yet another level of the professional therapeutic relationship, one that the psychotherapists understand.

The therapeutic aspect of the relationship itself

There are many different schools of psychotherapy and counselling, just as there are many different kinds of complementary therapies. On the whole, and unlike complementary therapies, practitioners of most schools tend to emphasise the relationship rather than the treatment aspect of the work. The psychoanalytic schools of psychotherapy work entirely with the relationship between therapist and client – this is the treatment. There are also types that don’t worry much at all about the relationship, notably the cognitive and behavioural therapies, which focus on the treatment, setting clear objective goals and planning strategies to achieve them. With the relationship foreground in the healing, the treatment, which in psychotherapy terms means the theoretical models about the mind and any tools that the therapists might use, takes on far less importance. Tools, for a psychotherapist, might be making what are called interpretations, which means saying just the right thing at the right moment to create a shift in the client’s understanding or awareness. Another tool is dream interpretation. Tools used by both psychotherapists and some CAM practitioners are visualisation, breath work or writing or drawing exercises.

In this sort of professional therapeutic relationship, we still have the boundaries, the practitioner and his or her use of interpersonal skills and self awareness, the treatment and the client. But we also have everything else that both parties are bringing to the relationship, some of which is conscious and spoken (Client to acupuncturist: ‘I’m a bit anxious about the needles. Will they hurt?’) and some of which is conscious but not spoken (reflexologist thinking about client: ‘You do look just like my horrible aunty Janet’). And then there is all the material that isn’t particularly conscious at all, such as our history as a CAM practitioner, and the client’s history as a client. And all our personal history and all of the client’s. Values, attitudes, prejudices, cultural background, gender and sexual orientation, religious and spiritual beliefs and the stuff that some people call our ‘baggage’, the unhealed wounds from the past, it’s as if all of this material is floating around inside the therapeutic relationship. The client’s relationship with her moth...