![]()

Chapter 1

Neurological Damage and Models of Rehabilitation

This chapter introduces the reader to the acquired brain injury (ABI) population for whom clinical techniques described in the book are designed – patients who have acquired neurological damage through traumatic brain injury (TBI), cerebral vascular accident (CVA), or an ABI from other causes. We first preface this with an overview of the architecture of the brain – the localization of various areas of functioning in the human cortex. The causes of neurological damage and the residual impairments in functioning that may occur are then outlined. The remaining part of this chapter describes stages of recovery, models of rehabilitative music therapy treatment, and some thoughts on music therapy assessments.

The brain and areas of functioning

Before we can examine the effects of neuronal damage on human functioning, an understanding of the brain and how the nervous system operates is needed. At the same time, it would be presumptuous to believe that a comprehensive description of the organization and functioning of the human central nervous system could be accomplished in just a few pages. Included in the following pages is a basic overview of the brain and its mechanisms as a foundation for the remaining chapters of the book.

The human brain, weighing about 1.4 kilograms, is a remarkable organ that has evolved and continues to evolve with time. It is the control centre for almost every part of human existence – from the beating of our heart to a walk down the street, from our memory of the past to our thoughts of the future, and from our conversation with others to the very depths of our private emotions. Almost from the moment of conception, the brain begins to develop and learn from experience. The rate at which the brain acquires knowledge in the early years of development is so high that it is hard to comprehend.

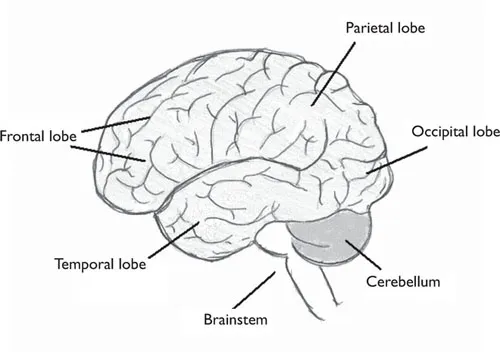

Historically, it was through the study of functional deficits that people presented with following damage to the brain that scientists first began to develop an understanding of how the brain works. Advances in the field of neuroscience were furthered with the emergence and ongoing development of brain imaging technology such as the electroencephalograph (EEG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission topography (PET), and computerized tomography (CT) scans. Every day, more scientific advances are made. So what do we know so far? First, the brain has three main structures – the cerebrum, the cerebellum and the brainstem. The cerebrum is divided into two hemispheres, left and right, each of which has four lobes – frontal, parietal, occipital and temporal. The outer layer of the cerebrum is known as the cerebral cortex or grey matter, while the inner layer of the brain is known as the white matter.

Neuroscience tells us that various regions within the brain are responsible for different aspects of human function (Figure 1.1) and injury to these regions will cause corresponding disturbances in human function.

Figure 1.1 The human brain

FRONTAL LOBES

The frontal lobes are located at the front of the brain and are the largest and most evolved of the lobes. The frontal lobes are very important in controlling aspects of cognitive, communicative, and physical functioning. The anterior (front) portion of the brain is called the prefrontal cortex and is involved in the control of higher cognitive functions such as concentration and attention, abstract thought, decision-making and judgement, personality, affect, memory, problem-solving and inhibition. The posterior (back) part of the frontal lobe consists of the premotor and motor areas which are involved in motor planning and voluntary motor execution, including the motor speech area. The right frontal lobe controls movements for the left side of the body and the left frontal lobe controls movements for the right side of the body. The left frontal lobe also contains Broca’s area, which is extremely important in language processing.

PARIETAL LOBES

The parietal lobes are located behind the frontal lobe at the top of the brain. The right parietal lobe is involved in visuo-spatial skills, such as finding one’s way around unfamiliar (or familiar) places, and awareness of space and relationship of self to surroundings. The left parietal lobe has some involvement in a person’s ability to understand spoken and/or written language. The parietal lobes also contain the primary sensory cortex which controls sensation (pressure, shape, weight and texture).

TEMPORAL LOBES

The temporal lobes are located on each side of the brain. The temporal lobes are involved in language comprehension and expression, memory for past experiences (e.g. conversations, art and music), and hearing.

OCCIPITAL LOBES

At the back of the brain are the occipital lobes. This is where visual information is processed, including visual reception and the recognition of shapes and colours.

CEREBELLUM

The cerebellum is a structure located beneath the occipital lobe and behind the brainstem. It is responsible for psychomotor function including muscle activity, coordination of movement, and balance. It coordinates the sensory input from the inner ear and the muscles to provide accurate control of body position and movement.

BRAINSTEM

The brainstem, found at the base of the brain, forms the link between the cerebral cortex, white matter and the spinal cord. It contributes to the control of consciousness and alertness, carries messages to muscles and nerves, and controls important body functions such as heart rate, blood pressure and respiration.

Other important areas within the brain include the thalamus, hypothalamus and limbic system. The thalamus is the brain’s relay station and channels impulses from the senses to the cerebral cortex. The hypothalamus controls the autonomic nervous system and thus regulates basic human functions such as hunger and thirst, body temperature, sleep and wake cycles, bone and muscle growth, and sexual hormone cycles. The limbic system is not a specific structure, rather a series of nerve pathways deep within the temporal lobes which form important connections with the cerebral cortex, white matter and brainstem. It is responsible for the control and expression of mood and emotion, and processing and storing recent memory.

Structural and functional organization of the brain

Now that we have offered an overview of the different areas in the brain and the functions they serve, it is useful to present descriptions of the events that need to take place within the brain to transform incoming sensory information into perception and behavioural responses. In particular, breaking down the brain’s structure at the neuronal level is useful. Again, note that the following descriptions are overviews of neuronal structure and functioning which are meant as an introduction the reader to basic cellular functioning, not comprehensive anatomical descriptions.

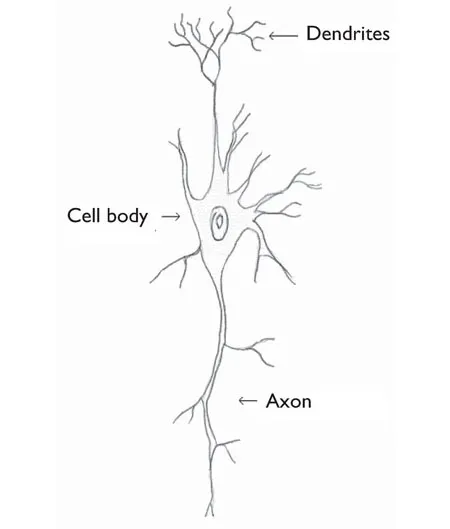

First, the brain is composed of two main types of cells, neurons and glia (Kolb and Cioe 2004). Neurons are the cells that carry out the brain’s major behavioural functions. Neurons (see Figure 1.2) consist of a cell body and two types of projections, the dendrite that receives information from adjacent neurons, and the axon that sends information to adjacent neurons. The majority of neurons are unable to undergo cell division or cell repair, so damage to neurons is irreversible. However, connections between various intact neurons can grow and be altered through brain injury.

Figure 1.2 Structure of a neuron

Second, the synapse is the key site of neuronal communication and learning. The process of sending information from one neuron to another is known as neurotransmission and occurs at the synapse. The space between the axon of one neuron (pre-synaptic cell) and the dendrite of another neuron (post-synaptic cell) is referred to as the synaptic cleft. When neurotransmission occurs, there is an electrical event which causes a chemical communication signal from one axon to cross the synaptic cleft and bind to receptors in neighbouring neurons.

Finally, glial cells play a role in neurotransmission. Glial cells are major constituents of the central nervous system and are crucial to the neurotransmission process as they maintain the signalling abilities of neurons. They have the capacity to strengthen the signal transmitted through the synapse and can play an important role in neuronal repair and recovery from brain injury. They facilitate efficient neurotransmission which, in the face of injury, becomes crucial for human functioning.

Now that we have established a basic understanding of how the normal brain operates, let us look at what happens when there is a disruption of neurological processes or injury to the brain.

Acquired brain injury

Causes

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is the collective term given to describe brain injury acquired following birth. These injuries are not hereditary, congenital or degenerative, but the result of a particular event. There are three main causes of ABI: cerebral vascular accident (CVA), traumatic brain injury (TBI) and hypoxic brain injury.

CVA may result from:

•blockage of a blood vessel(s) supplying blood to the brain (ischaemic stroke)

•intracranical haemorrhage – bleeding into the brain caused by rupture of blood vessels subsequent to high blood pressure or cerebral aneurysm (weakness in artery tissue)

•brain tumour – where the tumour presses directly on the brain tissue, or presses on blood vessels that restrict blood flow to the brain.

Some of the causes of TBI include:

•road traffic accidents

•falls

•blows to the head

•gunshot woun...