- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The German Army at Passchendaele

About this book

This WWI military history presents a detailed account of the third Battle of Ypres, in the Belgian village of

Passchendaele

, from the German perspective.

More than a century since the epic battle, the name Passchendaele has lost none of its power to shock and dismay. Reeling from the huge losses in earlier battles, the German army was in no shape to absorb the impact of the Battle of Messines and the subsequent attritional struggle.

Throughout the fighting on the Somme the German army had always felt that it had the ability to counter Allied thrusts, but following the shock reverses of April and May 1917, they introduced new tactics of flexible defense. When these tactics proved insufficient, the German defenders' confidence was deeply shaken. Yet, despite being outnumbered, outgunned, and subjected to relentless, morale-sapping shelling and gas attacks, German soldiers in the trenches still fought extraordinarily hard.

The German army drew comfort from the realization that, although it had yielded ground and paid a huge price in casualties, its morale was essentially intact. The British were no closer to a breakthrough in Flanders at the end of the battle than they had been many weeks earlier.

More than a century since the epic battle, the name Passchendaele has lost none of its power to shock and dismay. Reeling from the huge losses in earlier battles, the German army was in no shape to absorb the impact of the Battle of Messines and the subsequent attritional struggle.

Throughout the fighting on the Somme the German army had always felt that it had the ability to counter Allied thrusts, but following the shock reverses of April and May 1917, they introduced new tactics of flexible defense. When these tactics proved insufficient, the German defenders' confidence was deeply shaken. Yet, despite being outnumbered, outgunned, and subjected to relentless, morale-sapping shelling and gas attacks, German soldiers in the trenches still fought extraordinarily hard.

The German army drew comfort from the realization that, although it had yielded ground and paid a huge price in casualties, its morale was essentially intact. The British were no closer to a breakthrough in Flanders at the end of the battle than they had been many weeks earlier.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The German Army at Passchendaele by Jack Sheldon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War I. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

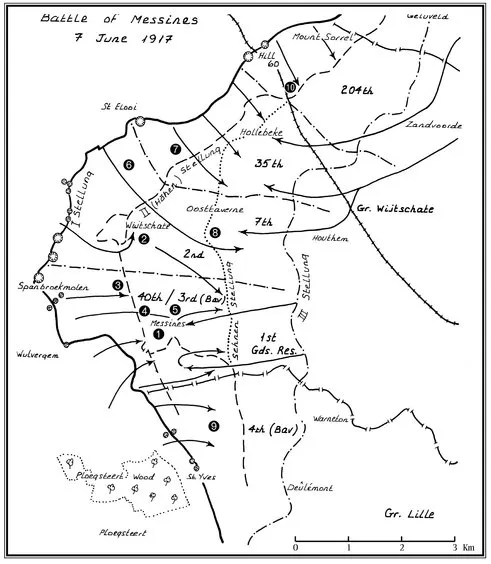

June and July 1917

The night of 6/7 June 1917 was comparatively quiet after several days of an intense bombardment, which had involved the use of over three million shells. All along the German front line in Flanders, sentries came and went, officers moved silently around their positions, checking that all duty personnel were alert and the occasional flare shot up in the sky, casting harsh and grotesque shadows on the desolate strip of territory between the lines that was No Man’s Land. The night wore on, dawn approached and tired company officers, their rounds and their paperwork complete for the night, were thinking of snatching a nap before the dawn stand-to when suddenly, at 4.10 am [3.10 am British time], the largest man-made explosion in history up until that moment was unleashed. From Hill 60 forward of Klein-Zillebeke in the north, to St Yves, east of Ploegsteert Wood in the south, nineteen massive mines, prepared in total secrecy over many months, blew up simultaneously.

The noise was heard up to two hundred kilometres away. Many thought that there had been an earthquake. Hundreds of German soldiers had no time to think anything. Killed instantly by the concussion, sent spinning into the air by the force of the blasts or vaporised by the intense heat in the centre of the explosions, they died in droves, swept away and forgotten, as the curtain rose on a battle which was to last five months, claim the lives of tens of thousands of soldiers on both sides, test men to the uttermost limit of human endurance and cast a long shadow over the lives of millions in the years to come.

The Messines ridge, known to the German Army at the Wijtschatebogen [Wijtschate Salient] had been a thorn in the side of the British army for three years. From its heights much of the Ypres salient could be overlooked and guns placed on it could bring down aimed enfilade fire on any point within it at will. For their part, the Germans were continually worried about the intrinsic vulnerability of the Wijtschatebogen. Concerns about the potential for attacks against it were a staple pre-occupation in the weekly situation reports issued by Staff Branch Ic of the Headquarters of Army Group Crown Prince Rupprecht during the early months of 1917.1 As a result, news that a preparatory bombardment had opened against it on 20 May came as no surprise to the defence.

From north to south of Group Wijtschate, commanded at the time by General der Kavallerie von Laffert, the 204th (Württemberg), 35th, 2nd and 40th (Saxon) Divisions, huddled in their dugouts, pillboxes and blockhouses, could only hold their positions and endure whatever the British artillery, directed by a large number of aerial observers, could throw at them. There are numerous accounts of the trauma of this bombardment. One of the observers of Field Artillery Regiment 32 of 40th Infantry Division, for example, has left us a graphic account of the manning of an observation post as the shells rained down around him: 1

“Until the end of May manning our observation post in Messines was still a fairly pleasant job. The British had started to engage Messines with heavy calibre shells, but they left the monastery, where we were located, alone. Day by day, this situation altered to our disadvantage. Suddenly, one day a shell landed right in front of us. It was only light calibre, so it had very little effect on our concrete pillbox. The following day a direct hit landed right on top of us. Once again it was only light calibre, thank heavens. Tiles and pieces of concrete landed on the wooden planks, but we still felt that it was a chance hit. Because of the increasing number of shells each day, it was quite possible that one had found its way accidentally in our direction. We were about to learn better.

“Gradually the light calibre rounds gave way to 280 mm shells, which crashed down with massive detonations, sending up huge pillars of earth and dust. Initially they landed beyond us, but gradually they crept closer. It dawned on us that our observation post was being deliberately targeted with super-heavy calibre rounds. As a result, for an hour at a time, two or three times a day, we were engaged with identically heavy shells. Our concrete pillbox heaved and swayed with each close impact by the shells. Thick powder smoke filled the room whenever a shell exploded really close, windows shattered, tiles and chunks of concrete rained down; the interior of our post often looked very rough indeed.

“It was noticeable that, whenever we directed a shoot against the mortars that were hammering our trenches, we in turn came under fire. It was perfectly obvious that the British had realised that there was an observation post here and were able, therefore, to bring effective fire down on it. There was not much left of Messines. What had once been an attractive village was reduced to a heap of ruins. The British, nevertheless, did not have all the luck when they engaged the village. Had they been more fortunate, they would have managed to land a direct hit on our post and snuff out all life. Try as they might, they never managed it. Not until the very last day before the attack did they manage to crush half of it with a direct hit.”2

Reserve Oberleutnant Scheele Adjutant 2nd Battalion Grenadier Regiment 4 3 2

“Our KTK (Leuthen) [(Command Post of the) Kampftruppenkommandeur = Commander of the Forward Troops]4 was nothing more than a heap of ruins. We lost all four corners in the early days of the bombardment. An extremely heavy dud landed right on the roof of the blockhouse and wedged there with its tip hanging directly above the entrance; not that that reduced the number of visitors. The Pappelhof was also badly hit but, despite that, it remained in remarkably good condition. The daily air battles were most interesting. It was far from rare to see the enemy flying in battle formations of sixty to seventy aircraft. We were not in a position to put up so many sorties but, when we did, the British tended to stay away.

“Leutnant Wellhausen was seriously wounded in the KTK. A shell landed right outside, sending showers of splinters through the small window and hitting Wellhausen. We were clustered close together round a table, because the pillbox only measured 1.5 x 2.5 metres and were almost blinded by debris, dust and flying earth. I ignored the firing and headed off out carrying my discipline files, which the regiment had sent forward to me. The British landed shells just behind me, but I escaped their effect behind the next traverse, having first thrown my case containing the files there. I rounded up some stretcherbearers for Wellhausen here.

“The British did not fire on the stretcher bearers carrying the stretcher. [After that] we stayed where we were and did not attempt to return to KTK Leuthen before it went dark. It was, of course, still engaged at night, but not with aimed fire. The air battles continued to entertain us. The aircraft made a special effort to destroy balloons. If one of the latter was shot down, the observers used to jump and descend to earth by parachute. When the aircraft fired phosphorous [incendiary] bullets, they left long trails of flame and made a most interesting sight. Those of us on the ground were frequently the targets of enemy aircraft; the boldest of these came down to twenty metres to fire at us.

“It went on like this day after day. By then we were worn down so much that, finally, careful watchfulness in the face of danger gave way to complete indifference. None of us believed any longer that we should escape this witch’s cauldron in one piece, so it was all the same to us if we met our fate a few days earlier than we otherwise might have done. Our situation was desperate, but it did draw us together. We went into our letter cases and drew out letters and photographs of our relatives to show to one another, [but] our conversation tended to be confined to speculation about when we should be hit.”

Reserve Leutnant Wolk, 3rd Battalion Field Artillery Regiment 1 5

“Swarms of enemy aircraft enhanced the efficiency of the artillery. They interdicted the rear areas by day and night, attacking all manner of live targets with bombs and machine gun fire. It was clear to us all what lay before us and everyone held his breath, waiting for the infantry assault which just had to come. In order to counter what was going on, our artillery counter-battery fire also increased in intensity. Despite high losses of men and materiel in the batteries, we plastered enemy batteries and mortar positions industriously. Our Green Cross gas shells [filled with phosgene, or chloropicrin, or a combination of the two] certainly silenced many a ‘Tommy’ battery.”

The 40th Division had returned to its sector of the Wijtschate front on 21 April after a brief rest and, between that date and 3rd June, had lost 1,300 men to various causes. Those who remained were tired out and overdue for replacement. In consequence, the 3rd Bavarian Infantry Division was moved forward to relieve it.

The relief was due to be completed by the morning of 7 June, but the final stages of the process were overtaken by events.

Leutnant Dickes Bavarian Infantry Regiment 23 6 3

“During the night 5/6 June 1917 the 3rd Bavarian Infantry Division relieved the 40th infantry Division in the Wijtschate area. Once more Bavarian Infantry Regiment 23 was heading for the trenches … The 1st Battalion was stationed forward, the 2nd Battalion was in reserve and the 3rd Battalion was on stand-by and was not involved in the relief until the night 6/7 June … At midnight on 5/6 June [the regimental staff] set off for the regimental command post southeast of Wijtschate. Already, on the far side of Tenbrielen (eight kilometres east of Wijtschate), heavy shells droned overhead and red, yellow and greens flares could be seen up ahead. In single file we pressed on past innumerable shell holes – the going seemed to be far worse than anything experienced on the Somme or at Arras – through gas-filled hollows as far as the command post, which was housed in two concrete blockhouses. The party finally arrived for the relief, dog-tired and soaked with sweat. Everyone could see that this was a real hot spot, but nobody realised just how bad things would turn out …

“At 4.15 am [sic] on 7 June,7 the earth suddenly shook violently, which made everything tremble … thinking that it had been caused by heavy shells landing nearby, Hauptmann Klahr, having shouted in vain to his batman, leapt outside. The sky was full of smoke and dust and thousands of British gun barrels were pouring out death and destruction. It suddenly dawned on everyone that the British, having mined forward over a long period, had blown up the entire front and launched the anticipated attack. What could our men outside possibly do? They had hardly arrived. They did not yet know the ins and outs of the position. Utterly overwhelmed by such explosions, what could be expected of them? Simultaneously, down came the British artillery fire, which further damaged the shattered remnants of the trench garrison lucky enough to have survived the explosions. Split into small nests of resistance, they held out forward. No support could get forward through it. The defensive artillery batteries had been neutralised and the battalions at readiness could not get to the front.

“About 5.00 am, the first report arrived from the front line. It stated that the British had blown up the positions held by 1st, 2nd and 3rd Companies Bavarian Infantry Regiment 23, had overrun them and that the Kaiserschanze (1,500 metres southwest of Wijtschate and located between the First and Second Positions), which was being defended by 4th Company Bavarian Infantry Regiment 23, had also been taken. In other words, the forward battalion had ceased to exist. At that point Reserve Leutnant Kliegel, commander of 9th Company, who, despite the fire, had managed to get forward, reported in. He was ordered to occupy the crest line to our front and the remaining reserve companies under Major Koch (Infantry Regiment 104) received the same order. To have delayed longer would have been dangerous.

“The two concrete blockhouses which housed regimental headquarters were visibly shaking from the impact of exploding shells. It appeared that the British rolling barrage had reached this line and was about to move on. The sound of small arms fire could be heard clearly in the blockhouses. Reserve Leutnant Heerget went forward to the crest and spotted that the British were only fifty metres away. There was no sign of support; some of our men had already pulled back. Reserve Leutnant Diehl was still up on the crest line, firing a machine gun for all he was worth and could not be persuaded to withdraw. ‘I have never seen targets like it,’ he said. But what could he and his machine gun achieve alone? He stayed where he was and was captured.

“The decision was now made to evacuate the command post. To have stayed any longer would have been tantamount to committing suicide. As we left the command post the British poured small arms fire at our small group at virtually point-blank range but, amazingly, nobody was hit. After racing away in bounds of hundred metres and fifty metres, the withdrawal continued at a walk; the wall of dirt and dust cutting out all visibility … The British rolling barrage was quite distinct, but our artillery was completely silent. We passed battery positions where the guns were still there and ammunition lay ready. Only the crews were missing. As we made our way to the rear, we did not hear our artillery fire a single round. Our airmen were also completely absent, whilst those of the British circled above and fired at us from close range. Finally, at 7.17 am, we arrived at Villa Kugelheim (a farm two kilometres to the east of Wambeke), which was the headquarters of 88 Infantry Brigade. Here we reported what had happened …

“Next morning, the 8th June, the regiment assembled near to Korentje (six kilometres east of Messines). There were about 600 altogether. Apart from one officer (Reserve Leutnant Seeburger), three men and the mortar platoon, the 1st Battalion was destroyed. Only a few remnants remained of the 3rd Battalion, which had been surprised on the march forward. The 2nd Battalion suffered the least … Within perhaps half an hour the regiment had lost twenty nine officers and more than 1,000 men. The great majority fell victim to British weaponry; a few ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- CHAPTER ONE - June and July 1917

- CHAPTER TWO - 31st July 1917

- CHAPTER THREE - August 1917

- CHAPTER FOUR - September 1917

- CHAPTER FIVE - 1 – 15 October 1917

- CHAPTER SIX - 16 – 31 October 1917

- CHAPTER SEVEN - November and December 1917

- APPENDIX - German – British Comparison of Ranks

- Bibliography

- Index