![]()

PART I

Mindfulness and the

Arts Therapies

Overview and Roots

![]()

Chapter 1

Mindfulness, Psychotherapy,

and the Arts Therapies

Laury Rappaport and Debra Kalmanowitz

Mindfulness is a practice of bringing awareness to the present moment with an attitude of acceptance and non-judgment. Often traced to the teachings of the Buddha 2500 years ago, mindfulness practices are also found in most major wisdom traditions. Ancient mindfulness practices are being adapted to secular contexts—psychotherapy, education, and work environments—in response to the numerous clinically standardized applications of mindfulness and meditation practices (Burke 2010; Chiesa and Serretti 2009, 2011; Fjorback et al. 2011; Hussain and Bhushan 2010; Keng, Smoski, and Robins 2011; Shennan, Payne, and Fenlon 2011). As Thich Nhat Hanh (2012) states, “When you have enough energy of mindfulness, you can look deeply into any emotion and discover the true nature of that emotion, If you can do that, you will be able to transform the emotion (p.89).” Mindfulness practices can be learned within spiritual and secular settings, depending on what is right for each person (client and therapist).

We begin this chapter with an introduction to mindfulness in its essence—outside of any religious or spiritual context. Next, we give a brief overview of its spiritual roots, historical influences in the field of psychology and contemporary culture that have led to the application of mindfulness approaches in psychotherapy, followed by a discussion of the relationship of mindfulness to the expressive arts therapies.

The Essence of Mindfulness

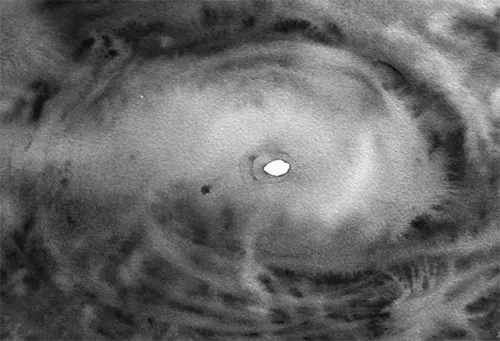

We would like to introduce the essence of mindfulness using an image and metaphor. Imagine a storm. Take a moment to notice the storm depicted in Figure 1.1.

What do you notice? There is a swirling that can include high winds, rain, and sleet. In the center there is a place in all storms that is called the “eye” of the storm. The qualities of the eye of a storm are calm, peaceful, and clear. The practice of mindful awareness involves taking time to access the “eye”—the part of us that can observe the storm—as it is. Mindfulness practices help us to find a center (eye or “I”) within ourselves to bear witness to the storm of thoughts, feelings, sensations, and all aspects of our experience, with acceptance.

Figure 1.1: Eye of the storm

Two Wings of a Bird: Experiencing and Witnessing

Mindfulness practice can also be compared to two wings of a bird (Spring Hill 1983). One wing symbolizes our experience; the other represents our ability to witness and observe our experience. If we only have our experience, we can get lost in the storm. If we are only in touch with the witness aspect of ourselves, then we can be detached and disconnected from the aliveness within our experience—whether it is joyful, scary, fun, and so forth. As birds need both wings in order to fly, so too do we. Mindfulness practices and the expressive arts teach us how to become aware of the inner witness while noticing and sensing our experience at the same time.

Spiritual Roots and Applications of Mindfulness

Although it is beyond the scope of this book to provide an in-depth review of the spiritual roots of mindfulness, we would briefly like to include a beginning overview of its roots in Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam (acknowledging there are other traditions as well). Awareness of mindfulness practices in different traditions can offer clients and therapists culturally sensitive options for those interested in learning within their cultural or religious roots.

Buddhism

As previously mentioned, the roots of mindfulness are most often attributed to the Buddha’s teachings, approximately 2500 years ago. The Buddha’s discourses describe an Eightfold Path for reducing suffering and living with greater happiness and peacefulness. The teachings, or Dharma, is “not a set of doctrines demanding belief but is a body of principles and practices that sustain human beings in their quest for happiness and spiritual freedom” (Bhikku 2011, p.20). The eight aspects include: (1) right view, (2) right intention, (3) right speech, (4) right action, (5) right livelihood, (6) right effort, (7) right mindfulness, and (8) right concentration. Thich Nhat Hanh (1975, 1976) describes the seventh aspect in the Buddha’s Sutra of Mindfulness:

When walking, the practitioner must be conscious that [s]he is walking. When sitting, the practitioner must be conscious that [s]he is sitting. When lying down the practitioner must be conscious that [s]he is lying down… No matter what position the body is in, the practitioner must be conscious of that position. Practicing thus, the practitioner lives in direct and constant mindfulness of the body… (p.7)

As can be seen from this quote, mindfulness is awareness. The Buddha describes four foundations of mindfulness—contemplation of the body, feelings, states of mind, and phenomena. Mindful breathing is a fundamental practice that serves as an anchor to notice the continuous arising and passing of thoughts, feelings, sensations, and phenomena. Mindfulness practices help to access an inner witness and a more spacious aspect of ourselves to examine the true nature of our experience; to dis-identify with feelings, thoughts, and sensations that are within our experience but not who we really are; understand that everything in life is constantly changing (impermanent); and to gain insight and compassion.

Buddhist mindfulness practices include formal practices—sitting meditation, walking meditation, body scan, eating meditation, and meditations on lovingkindness (bringing gentleness and compassion towards oneself and others)—as well as informal practices carried into daily life, such as practicing mindful breathing while doing the dishes, stopping at a red light, or in response to your cell phone ringing. Within Buddhism, mindfulness is taught through a variety of approaches, including Vipassana (Hart 1987), Insight Meditation (Goldstein 1993, 2007; Kornfield 2009; Salzberg 2011), Tibetan (Chodron 2013; Tenzin Gyatso 1995) and Zen (Hanh 1975, 1976, 1991).

Hinduism

Hinduism predates Buddhism and includes many practices for cultivating mindfulness. One basic approach to meditation consists of repeating a mantra—a sacred word, name, or sound. The practitioner silently repeats the mantra coordinating it with the in-breath and the out-breath—and notices thoughts, feelings, sensations, and occurrences in the environment—allowing them to pass by like the clouds in the sky. During this process of meditation, the steadiness and vibration of the mantra help one to access the inner witness (saksin)—who non-judgmentally notices the coming and going of inner and outer experiences. The witness helps the practitioner to observe and dis-identify with feelings, thoughts, and sensations that can lead to an experience of oneness with Consciousness, Self, or God (Anantananda 1996; Shantananda 2003).

Christianity

Mindfulness is applied in Christian traditions through contemplative prayer and meditation. Meninger, Pennington, and Keating (Keating 2009; Pennington 1982) developed the Centering Prayer that is based on practices by the Desert Fathers and Mothers from the fourth and fifth centuries and inspiration from Thomas Merton (1960, 1961). In Centering Prayer, the practitioner chooses a word, phrase, or sacred symbol that gives consent to God within, followed by closing the eyes and sitting quietly. In contrast to continuous repetition of a mantra, the sacred word or symbol is only focused on when the practitioner notices getting carried away into thoughts, feelings, and other distractions. Father Keating describes treating the thoughts and distractions with a “smile, friendliness, or jolliness” (Keating 2008). Blanton (2011) compares the Centering Prayer with mindfulness and discusses its application to psychotherapy. Symington and Symington (2012) present a Christian model of mindfulness based on three pillars—presence of mind, acceptance, and internal observation. A crucial aspect of Christian mindfulness is experiencing the presence of God.

Judaism

Although Jewish contemplative practice dates back thousands of years, meditation practices have “often been hidden in the oral tradition passed directly from teacher to student, or in Kabbalistic writings that are difficult to decipher” (Cooper 2000, p.6). Jewish meditation is understood to be the ability to master one’s thinking, or the flow of consciousness which is seen as residing in the soul, guided by kavanah (intention) (Kaplan 1995). In recent years, Jewish meditation and mindfulness practices have become more accessible and are being introduced into many synagogues and practice centers (Cooper 2000; Kaplan 1995; Roth 2009; Schacter-Shalomi 2011, 2012; Slater 2004).

Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi (2011, 2012), founder of Jewish Renewal, studied various Eastern meditation traditions and describes how some forms of Jewish meditation are similar to Buddhist mindfulness practices except that the intention—kavannah—of Jewish meditation is the awareness of God’s presence: “…when thoughts and feelings arise in your meditation, you can release them to God” (p.45). Rabbi Schacter-Shalomi (2013) describes this further:

When something arises, to also make a window, as it were, to let God in. You would do everything the same way but you would open a window and say, “God look into this consciousness with me.” It becomes a prayer.

Islam

The mystical branch of Islam is Sufism. The poet saint Rumi, born in 1207, founded the Mevlevi Order of Sufism, and is often quoted to inspire states of awareness, mindfulness, compassion, ...