![]() 1 – INTRODUCTION

1 – INTRODUCTION ![]()

CHAPTER 1.1

Contextualising the Model

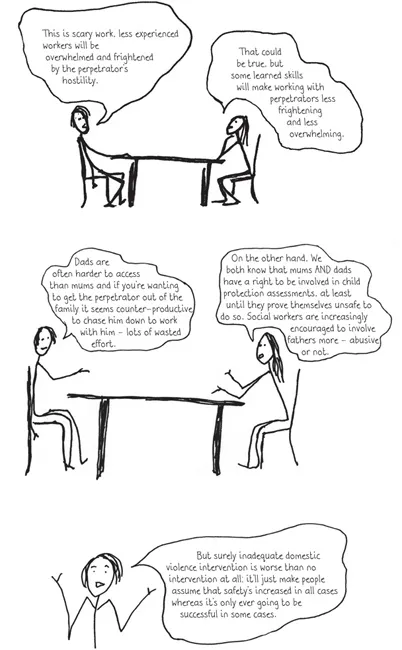

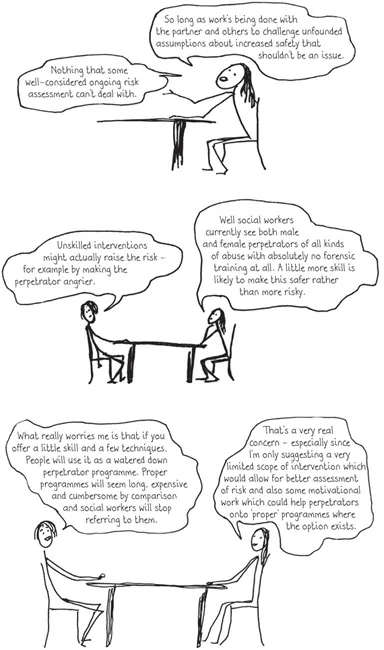

Child protection social workers and family support workers can today complete their training without learning a single thing about how to work with domestic violence perpetrators. Yet in case after case they are expected to do just that. This peculiar situation has arisen in part due to a controversy in the domestic violence (DV) field surrounding skilling up frontline professionals to work with perpetrators. The arguments on each side look something like this:

Despite all this, the benefits of skilling frontline workers to do this work remain compelling: in the absence of any work with the perpetrator, the onus falls upon the woman to undergo assessment and ultimately to change. She is the one that social workers and other professionals feel frustrated with and sometimes accusatory towards. She becomes the problem and is seen as ‘failing to protect’. Working with the perpetrator places the emphasis to change back on the person causing the problem.

But perhaps most importantly, a well-timed and well-placed intervention might genuinely make some people less risky and their children and (ex-)partners safer.

This book is primarily aimed at frontline practitioners like child protection social workers who want to engage with someone they suspect has been abusing an intimate partner. The exercises and techniques this handbook offers are aimed at helping them make the most of their limited client contact.

This handbook is not going to provide practitioners with a whole DV perpetrator programme. Accredited perpetrator programmes are long (24 weeks and upwards) and the research suggests that the resultant changes are deeper and more sustainable. There are lots of excellent perpetrator programmes out there – at the back of this book we provide the details of Respect, a UK-based organisation whose role it is to signpost practitioners and abusers to what’s on offer, both in terms of models and UK services. We are aware that recent changes to the England and Wales child protection system have set a strict 26-week deadline for care proceedings to finish. This is because delays to decision-making can have an adverse effect on outcomes for children. This change to the system also creates implicit pressure for ‘quick fix’ interventions. Of course, pressure for shorter (and cheaper) interventions is not limited to England and Wales. Whilst it would be wonderful if we could find a brief intervention which reliably produced sustainable reductions in abuse and violence in the home, there is no evidence that such an intervention exists at the present time, and the exercises in this book are certainly not designed to serve that function though they can be used more positively, for ‘treatment’ to be tested out before proceedings start.

The other thing this book is not is a guide to anger management, though it includes a couple of anger management techniques. This book is firmly directed at work with abuse in intimate relationships – abuse that’s usually about all sorts of expectations that people have of one another because they’re in an intimate relationship. Additionally, this book is not about anger per se – which is just an emotion, and one the authors have no issue with – it’s about abusive behaviour, which is a whole different ball game.

We very much hope that the techniques we are suggesting here will be delivered alongside some separate work with the victim of the abuse. That part of the intervention is probably going to be the best way to increase family safety. What’s more, there’s always a danger that work with the perpetrator can mean that the victim feels relieved and reassured, but this may be unwarranted. A lot of women get back with partners or cancel plans to leave for a refuge when their abuser promises to get help. It could be that the abuser being worked with will prove impervious to these techniques and so it’s important to make sure that the victim is really clear that there’s no guarantee of change. While somebody works with the abuser, somebody else (ideally not the same person – that can get complicated) has to be encouraging the victim to continue assessing and planning for the safety of herself and the children.

We’re not going to say any more about this, nor try to explain how to do safety planning work and all the other techniques that might help victims of domestic abuse. That’s another book altogether.

We came across a ‘brief guide’ the other day which was 260 pages long, and we weren’t happy. We’re assuming that those who bought this book were attracted to its brevity. This brevity has been achieved by being very clear as to what it will and won’t include.

So let’s just summarise that. This book will not:

•teach how to work more effectively with the victim of the abuse

•explain how to assess or work with children living with family violence

•provide a full perpetrator programme

•teach group work with perpetrators

•prepare workers for undertaking a risk assessment for care proceedings

•help significantly with any research or theory papers – it’s not an ‘academic’ text.

What this book will include – and in fact all it offers – are a few key techniques for those who end up with just a few sessions with a DV perpetrator (between one and ten meetings) and want to learn to:

•briefly assess them

•prepare them to do a full perpetrator programme

•make the most effective possible interventions to decrease the risk in the meantime.

The authors of this book have a combined total of 40 years’ experience of working with DV perpetrators. We’ve been training people to make frontline interventions for about half of that time, and now train around 500 practitioners a year. We’ve developed a sense of what’s most effective, easiest to learn and realistically applicable for frontline practitioners who aren’t specialist perpetrator workers. We haven’t reinvented any wheels here – we’ve just picked out the most commonly used and effective ways of working, including approaches from motivational work, anger management, cognitive behaviour therapy and feminist models. These are:

•building a working alliance whilst tackling denial and minimisation

•assessment and risk

•signals, time outs and safety plans

•extending the definition of violence and abuse

emotional abuse and intimidation

abusing cultural privilege

•analysing incidents of abuse

•working on the impacts of abuse

•conflict resolution

•referring out.

We hope it helps.

Kate Iwi and Chris Newman have been working with domestic abusers in the UK for 20 years. To find out more about the training and consultancy they can provide go to

www.fsa.me.uk, or contact them at

[email protected] or

[email protected]