![]()

PART 1

GENERAL ISSUES

Why would you buy a book like this?

A diagnosis of ASD can come as a logical conclusion of growing recognition that someone is different; it can come as part of defining evidence-based practice.

Defining evidence-based practice

A logical place to start, central to much of what follows, is: ‘What do we mean by evidence-based practice (EBP)?’

It seems a ‘no-brainer’ that we should base what we do on what is known to work best. Surprisingly, this is a recent idea. It comes from the work of a Scottish physician called Archie Cochrane.1 He saw that the growing numbers of studies on medications and surgical treatments often came to different conclusions, were difficult to interpret, took more and more time to wade through and were confusing rather than helpful. We needed ways to combine research results. He developed a means of combining results to arrive at a consensus. The Cochrane Collaboration has continued to develop his general approach (see www.cochrane.org).

EBP is a clear approach with a specific meaning and agreed methods. It remains a method of combining research findings to guide practice:

the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.2

It is now used in many health-related areas from medicine to clinical psychology,3 speech and language therapy4 and occupational therapy.5 Outside health, it is found in education,6 social work7 and government administration.8

EBP relies on evidence gathered with appropriate, well-researched measures. The more complete that information, the stronger the conclusions you can draw, but findings can be biased by gaps in data.9

In the UK, three groups review evidence-based practices in ASD:

•SIGN (the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network) (www.sign.ac.uk), which provides cross-disciplinary guidance for Scotland.

•NICE (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) (www.nice.org.uk), which provides best-practice guidance for England and Wales.

•The Cochrane Collaboration (www.cochrane.org).

SIGN makes its recommendations irrespective of any resource implications; NICE makes recommendations that are explicitly resource constrained. The Cochrane Collaboration does not make explicit recommendations but systematically reviews the evidence.

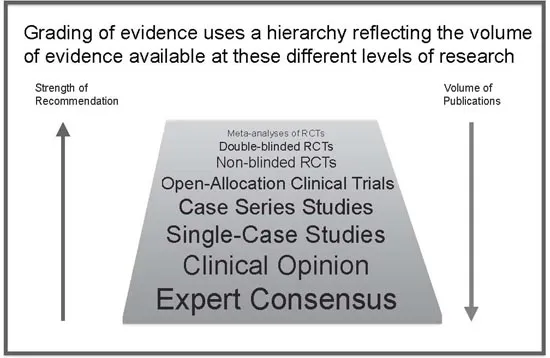

These groups use similar methods. They map studies onto a broad ‘hierarchy of evidence’ (Figure Part 1.1) using the study size, design and whether assessments and subjects are blinded. The results of meta-analyses on randomised controlled trials are given most weight, while reports on cases or small series are given little weight. This is how the EBP model is supposed to be applied. It works well for larger drug trials but can be unhelpful in areas like ASD where the literature seldom fits this model.

Figure Part 1.1 Hierarchy of evidence

All groups start by reviewing the literature and applying their criteria to the evidence. Evidence is graded for each piece of relevant research and then combined, taking into account things like the numbers studied, the assessments, length of follow-up, statistical analysis and outcomes. All the systems are very similar and you would think that they would reach similar conclusions.

Do they differ? SIGN and Cochrane rely on the above process exclusively, irrespective of its financial and practical implications. In contrast, NICE operates within explicit financial resource constraints, and most of its recommendations apply only to direct costs. With all three, the approach and limitations are clearly stated.

To date, these groups have given little consideration of indirect costs from things like increased staffing, additional training, or the capacity-building implications of novel evidenced approaches.

Reviews of the literature should tell you how studies were selected and rated; how research was identified; why some studies were rejected (‘exclusion criteria’) and why the others were accepted (‘inclusion criteria’); how each study was rated and reviewed; and how the information was pulled together to draw conclusions and make recommendations.

The basis for each conclusion should be clear (‘Why did you say to do that?’). If you are not convinced, double-check the information (‘What was their evidence? – I want to be sure they got it right – how do I check?’). This is important where recommendations are controversial, involve major expense or require significant changes.

Until recently, a lot of research has been missed by the search algorithms used for the SIGN and NICE reviews. The autism research in online science journals like the SCIELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online) network, largely from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Mexico, Portugal, South Africa, Spain and Venezuela, has only been easily accessible outside South and Central America since 2012. Much mainland Chinese research only became accessible in 2008 with the linking in of the Chinese Science Citation Database (CSCD) to Western search engines. Neither SCIELO nor CSCD were used in the reviews conducted for the current SIGN update, and most were excluded from recent NICE guidance as the initial language for publication was not English.

A clear and transparent process for reaching specific recommendations allows anyone who questions the conclusions to check them out for themselves.

Why this emphasis on making practice ‘evidence based’?

This is to ensure that practice is altered based on the evidence and that changes are measured against this. The adoption of this approach is partly due to resource limitations, and partly to a more research-oriented model being accepted by central government.

Tighter budgets make justification of practice changes increasingly important, particularly if they involve additional short-term expense for longer-term gain. Changes need to be based on information on what should work, not just the whims of a political administration.

A different path – comparative effectiveness research (CER)

A slightly different approach to applying research evidence arose from changes to healthcare access in the US during Barack Obama’s presidency. Novel ways were developed to establish clinical effectiveness and best value for money when different approaches were available. This was achieved using a head-to-head approach now called CER or comparative effectiveness research.10–13

The Patient Centered Outcome Research Institute (PCORI) was set up under the US Affordable Care Act in March 2010. PCORI funds targeted research and commissions CER literature reviews. The aim is to ensure that the most effective mix of treatments is endorsed and the ‘relative health outcomes, clinical effectiveness, and appropriateness’ of different approaches to any problem are investigated. It has ongoing Federal funding, but according to the Affordable Care Act, PCORI is an independent non-profit organisation that assists in informing the health decisions of ‘patients, clinicians, purchasers, [and] policy-makers’.

PCORI, in the medium term at least, is having a major influence through funding CER and its new approach to evaluating evidence. It is having an impact on how a large body of new research is being structured, evaluated and carried out, and is appearing in the clinical literature. One advance is that different approaches to the same problems are being compared on the same outcome measures. The ethos is to compare different available approaches against each other to assess their relative costs and benefits.

Conclusion: EBP and CER provide means to assess current practice. So far they have helped to identify the methods and gaps in knowledge but provided little evidence on best practice.

What if there’s no good evidence?

Pulling together the available research to inform practice works well where there is a reasonable body of...