![]()

PART 1

THEORY, RESEARCH AND RESOURCES

![]()

1

WHY RHYTHM?

Despite all the many wonders that modern science has endowed us with, we still battle, in our Western societies, a rising tide of psychological distress and social isolation. Here the dominant treatment is to prescribe drugs and talk-based therapies, a response that contrasts markedly with the approach of many other cultures that utilise mindful, non-verbal, rhythmic activities, such as dance and drumming as core parts of their healing traditions.

My first experiences of integrating rhythmic music into my practice were primarily inspired by the motivating and connecting power of music. Where days before, individuals had to be followed up to attend my sessions, now they were waiting at the classroom or office door or sometimes in the car-park wanting to help me unload! The presence of the drums changed the nature of our engagement from formal to fun and allowed us to find a fast, non-verbal connection to each other. As well, the drumming noticeably impacted the way that individuals worked together in the groups I ran, often allowing them to form a supportive team in a short period of time and giving them a sense of belonging and place. Response to rhythm is an almost irresistible impulse that has been utilised across human history as a means to connect people in community, promote collaboration and cooperation, and develop social cohesion – fundamental principles of group survival as well as core elements of therapeutic recovery.

Rhythm is the element of music associated with timing and repetition. Of all musical elements, rhythm is the one that binds people most closely, synchronising elements of the brain, and our emotions. When people talk about being ‘in tune with each other’ or ‘in time with each other’, this is what they mean. Rhythm extends well beyond music to encompass all elements of life, from the vibrations of the smallest atom to the cyclical rotations of the universe. Rhythm in this broader sense is denoted as ‘any predictable pattern over the course of time’. As practitioners or educators we can use the theme of rhythm to explore many facets of human behaviour and how these synchronise with the rhythms (patterns) of life that contextualise them.

Our earliest experiences of rhythm go back to the womb and the dominant presence of our mother’s heartbeat. Studies have shown the foetus at 15 weeks responding to changes in rhythm and, in the third trimester, being able to differentiate rhythmic intonations of the mother’s voice (DeCasper et al., 1994). The heartbeat rhythm is used across the Rhythm2Recovery model at tempos aligned to a relaxed body state (60–100 beats per minute). For most of us the womb was a secure place and the heartbeat remains a comforting rhythm that can reduce stress and aid relaxation. Leading trauma advocates hypothesise that the influence of the rhythmic vibrations of the heartbeat on the brainstem and midbrain regions during the time of their formation and organisation in the womb, and across the first years of life, makes a case for the use of similar somatosensory rhythmic interventions for people whose homeostatic systems require realignment (Perry and Hambrick, 2008). Patterned, repetitive rhythmic activities can be found in the healing and mourning rituals – dancing, drumming, swaying and chanting – of all cultures around the world.

With the advent of neuro-imaging technology in the 1980s the use of rhythmic music and exercise in health practice has received increasing support from the scientific establishment. Rhythmic music has been shown to impact areas of the brain closely connected to movement, emotional memory and impulse control. Brainstem neurones have been shown to fire synchronously with tempo, leading to theories that music may modulate a range of brainstem-mediated areas, such as our heartbeat rate and blood pressure levels; and in so doing, may be utilised to assist in the regulation of stress and arousal (Chanda and Levitin, 2013). With stress now at unprecedented levels, and music widely recognised as a common alleviator of the condition, this additional research is not before time.

Leading trauma authorities have now incorporated rhythmic exercises, including music and movement, into their recommendations for effective treatment in response to evidence linking rhythm to the realignment of homeostatic states disrupted through ongoing activation of the brain’s stress response (Perry and Hambrick, 2008; Van Der Kolk, 2014). Musical rhythm and tempo likely affect central neurotransmissions that maintain cardiovascular and respiratory control, motor function and potentially even higher order cognitive functions (Chanda and Levitin, 2013). Impacting these primal areas of the brain allows rhythmic music to heal beyond the reach of words.

1.1 Rhythm, Repetition and Learning

Since the beginning of recorded human history, repetition, a core element of rhythm, has been at the heart of learning. In ancient Greece, Aristotle highlighted the role of repetition in learning by saying ‘it is frequent repetition that produces a natural tendency’. In all areas of learning, repetition and practice are central to levels of attainment and skill (Campitelli and Gobet, 2011). Learning through repetition works because of the way it impacts the brain, strengthening neural connectivity through a process called myelination, which coincides with the development of specific cognitive functions, including memory (Mabbot et al., 2006). The importance of repetition extends to learning new behaviours, through repeated observations and practice, and enhanced by self-corrective adjustment based on feedback of performance.

In the Rhythm2Recovery model the use of rhythmic music and movement provides reinforcement for higher order cognitive learning. The repetitive stimuli of drumming elicits increased levels of focus and attention and, when paired with a learning objective such as social awareness, can improve the level of response (comprehension). We see advertisers taking advantage of this principle every day to maintain customer focus. Exercises in the Rhythm2Recovery program, in which vocal affirmations of self-worth, or behaviour change, are made on top of a regular rhythm, utilise this function. The pairing of rhythmic music and movement to reflective discussions on social and emotional learning develops a reinforcing association between the pleasure, focus and motivation that music engenders and important psycho-social learning concepts that might otherwise be challenging and lead to individuals withdrawing from therapy.

1.2 Rhythm as a Metaphor for Life

Rhythm permeates every aspect of life; we are rhythmic beings living in a rhythmic universe.

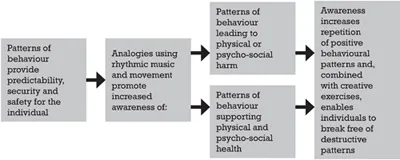

As such, rhythm provides the perfect metaphor for describing life and the way it interacts in all its complexity. Rhythms are patterns, and patterns (including habits and routines) dominate human behaviour. Metaphors are used to enhance the therapeutic encounter and can assist in both containing and extending emotional awareness. The use of metaphors is also an avenue for increasing the safety an individual feels when discussing sensitive issues, by substituting and reframing personal experiences and helping individuals tolerate aversive feelings that they may experience on their journey of self-understanding. Using metaphor allows us to create a safe space where the individual/s can explore their own story, test their intuition, their ideas and their judgment, and from there, safely and sensitively explore topics that later can be discussed more openly, outside of the privileged world of storytelling (Lou, 2008).

In the Rhythm2Recovery model this metaphor can be explored in dimensions limited only by the facilitator’s imagination and its relevance to the needs of the individual/s they are working with, including:

•rhythms/patterns that are healthy

•rhythms/patterns that are dangerous

•rhythms/patterns of strength

•rhythms/patterns of deceit

•rhythms/patterns that conflict

•rhythms/patterns of stress and anxiety

•rhythms/patterns that are in balance with each other

•rhythms/patterns in nature

•rhythms/patterns of comfort and security

•rhythms/patterns of fear and distress

•rhythms/patterns in our communication

•rhythms/patterns in our parenting

•rhythms/patterns in leadership

•rhythms/patterns of conformity

•rhythms/patterns of rebellion.

The list goes on…

See Section 15.2: A Life in Rhythm for more detail on the use of these analogies.

![]()

2

THE RHYTHM2RECOVERY MODEL

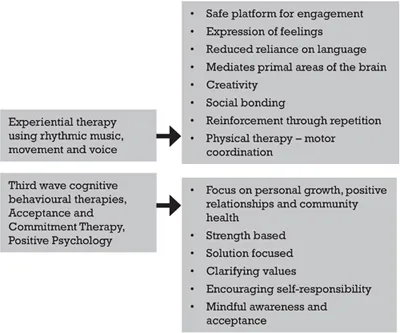

The Rhythm2Recovery format is an integrative model of practice combining experiential therapy techniques with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) influenced by the third-wave approaches of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Positive Psychology (PP). These newer cognitive approaches are strength based and focus less on exploring problems and more on finding solutions. Although the Rhythm2Recovery model owes much to the influence of these new cognitive approaches, it differs critically in the weight it gives to the role of thoughts in influencing behaviour. Developmental and neuro-imaging studies show that for many people who enter therapy, highly active primal brain areas (limbic system, brainstem) are driving behaviour, while the thinking, rational part of our brains (frontal lobes) are less active (Van Der Kolk, 2014).

The use of rhythmic music (drums and percussion), rhythmic movement and song make up the experiential elements of a Rhythm2Recovery program, with exercises designed to deliver physical and psycho-social benefits whilst concurrently exploring universal life-skill themes. These experiential exercises are then combined with reflective discussions utilising a cognitive-behavioural framework. This combination increases awareness and focus, expanding perspective and understanding and empowering personal growth. The program materials offer a large degree of flexibility for the practitioner to adapt the content of any specific session to the needs of a wide range of individuals or groups.

The Rhythm2Recovery approach is predominantly psycho-social, exploring the interaction of individual psychology with the social environment. The strength-based, solution-orientated focus of the Rhythm2Recovery model avoids the powerlessness often associated with diagnosis and the defensiveness triggered by examining too closely the personal challenges faced by an individual. A strength-based approach also reduces the likelihood of re-traumatisation that may occur when the focus turns to an individual’s problems or pathology. The focus on strengths and solutions also allows the program to be utilised in both clinical and educational contexts. Psycho-social education, often termed social and emotional learning (SEL), is now a key element of school-based education and a mandatory curriculum unit in many school districts – it is closely associated with improved school climate, reduced levels ...