![]()

PART I

Autism

THE BASICS

For many people, being diagnosed with autism is a life-changing event. However, it can take a long time to process this new information and accept the diagnosis, particularly when you don’t have enough information about autism to know how to react or even what it is you are reacting to. There is often a period of adjustment during which you question everything you thought you knew, which can leave you feeling confused and insecure. It is common to doubt the diagnosis or deny it altogether, and you might be unsure who you should tell, who to go to for help, or even what help you might need.

This part of the book is written to help you during this time. In particular, it explains what autism is, how it affects you, and where to find out more. It dispels some of the unhelpful myths that exist about autism, offers advice for discussing your condition with others, and provides explanatory models that can help illustrate different aspects of autism. It also gives details on the services and therapies that can assist you both during this time and moving into the future.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

What Is Autism?

This chapter tells you everything you need to know – everything important, at least – about autism. In particular, it gives you an overview of the condition, explains the jargon that is used within the autism community – that is, people with a diagnosis, their families and friends, carers and healthcare professionals – and helps dispel some of the unhelpful myths that surround this subject.

What is the autism spectrum?

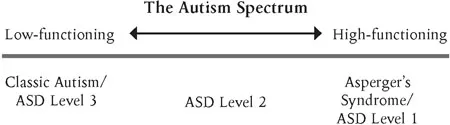

The current thinking about autism is that it is a developmental disorder encompassing a range of symptoms, particularly difficulties with communicating, socializing and understanding emotions. People with autism are placed on a sliding scale of severity known as the autism spectrum (see Figure 1.1). Traditionally, at one end of the spectrum is classic autism, roughly equivalent to Autism Spectrum Disorder Level 3, a condition typified by mental disability and severe learning difficulties. Asperger’s Syndrome and ASD Level 1 are towards the other end of the spectrum, and we are often of normal to high intelligence and require far less support in order to function.

Since the term ‘autism’ historically carries with it the sense of the non-talking, low-functioning end of the spectrum, many people like to stress how close to ‘normal’ they are by describing themselves as high-functioning. Confusingly, in the past high-functioning autism was a diagnosis in its own right. When someone says they have ‘high-functioning autism’, it can therefore mean they are at the upper end of the spectrum and have either Asperger’s Syndrome or ASD Level 1, or that they have a specific diagnosis of high-functioning autism. While it is important to be aware of this distinction, you don’t need to get hung up on it as high-functioning autism, Asperger’s Syndrome and ASD Level 1 are very similar conditions and often spoken of interchangeably.

Figure 1.1 The autism spectrum

What causes autism?

Nobody knows for sure. Some argue that it’s genetic and passed on from parents, and certainly most of the people I know with autism think that at least one of their parents has the condition but hasn’t been diagnosed. Others claim it comes from influences in the womb, certain conditions of the mother or even some postnatal incidents, but these ideas are still in their infancy. What is categorically certain is that it is not caused by the MMR vaccine, regardless of what certain celebrities and some of your relatives might say.

Is it Asperger Syndrome or Asperger’s Syndrome? ASD Level 1 or autism?

Really, it’s entirely up to you what you call your condition. There is not yet a consensus on terminology for the ASD diagnosis. Asperger’s Syndrome, on the other hand, is variably referred to as Asperger Syndrome, Asperger’s Syndrome, Asperger Disorder or just Asperger’s, often shortened to simply AS. Sometimes people pronounce it with a soft ‘g’, sometimes with a hard ‘g’. More important is to understand how the autism community talks about it. Many with the condition call themselves ‘Aspies’, and refer to people without autism as ‘neurotypicals’ or ‘NTs’, that is, people with ‘normal’ or ‘typical’ neurological functioning. It remains to be seen whether people diagnosed with ASD Level 1 will adopt the term ‘Aspie’ for themselves or come up with something new. This makes it an exciting, though confusing, time to be autistic.

What is the Triad of Impairments?

People with autism are said to experience difficulties in three key areas, known as the Triad of Impairments. These are:

•social communication – interpreting spoken and unspoken language

•social interaction – the unwritten rules of social relationships

•social imagination – understanding how other people think.

While treated as distinct categories, these three areas overlap significantly, and it might be simpler to think of the Triad of Impairments as ‘difficulties with socializing’.

How does autism affect social communication?

Most people with autism have difficulties interpreting the non-verbal language that makes up much of our social communication – that is, posture, hand gestures, facial expressions, tone of voice. The severity of this problem ranges from those who cannot differentiate a smile from a frown or a hostile tone from a friendly one, to those who have a general understanding of these areas in theory, but in practice get it wrong from time to time. We can also struggle with regulating our own body language and voices, finding it difficult to express ourselves in a way that other people can sufficiently understand. In particular, many people with autism struggle to make eye contact.

These problems are compounded by the fact that people with autism often have a literal interpretation of language, and can be rather pedantic about grammar and meanings. For example, a neurotypical person might say, ‘Chuck me that hammer,’ or, ‘Can you run and get me a coffee,’ causing an Aspie to literally throw a hammer at them or run to the coffee machine, when what they actually mean is, ‘Pass me that hammer,’ and, ‘Can you walk and get me a coffee.’ In order to minimize this confusion, some people with autism use very formal, precise language, leading to a monotonous tone of voice and sentences that don’t flow naturally, no matter how grammatically correct they might be.

Another key difficulty in social communication is that, given the literal interpretation of language and problems interpreting non-verbal communication, many people with autism can struggle to tell when someone is being sarcastic or joking. When somebody says, ‘Oh well done, that was really clever,’ when they really mean, ‘You idiot,’ it can confuse a person with autism. Once again, the severity of this problem differs from person to person, and I know numerous people with autism who have a finely developed sense of humour and a hearty appreciation of sarcasm.

How does autism affect social interaction?

People with autism often do not understand the unwritten social rules that govern modern life, and may have to consciously process and learn things that people without the disorder learn intuitively while growing up. These are such skills as knowing how to have conversations, forming and maintaining social relationships, and dressing or behaving appropriately for the given situation. Someone with autism may tell the truth – ‘Yes, you do look fat’ – when by social convention they’re expected to tell a white lie; talk when they’re supposed to be quiet; or raise inappropriate topics of conversation, such as trying to discuss advanced electrical engineering with the postman, or describing your recent bowel operation at a dinner party.

While most with high-functioning autism desire social relationships, we often don’t understand how to make friends or how to keep them. Since we might struggle to grasp what is considered ‘normal’ behaviour, we can sometimes be considered a little ‘weird’. For example, while it might be acceptable to swear when having informal conversations in a bar, the same is not true in a job interview. Similarly, we can encounter difficulties when crossing the boundary between friendships and romantic relationships, since the latter are covered by completely different social rules. These difficulties with social interaction can make the social world a demanding and stressful place for those on the autism spectrum.

How does autism affect social imagination?

The third aspect of the Triad of Impairments is social imagination. This is entirely different from conventional imagination, and indeed many on the spectrum are creatively talented. Social imagination is often referred to as Theory of Mind, and this is perhaps an easier way of thinking of it. Those on the spectrum are said to find it difficult to imagine what is going on in the minds of others. This inevitably impacts on a person’s ability to see things from another’s point of view, an essential skill in social relationships, and can lead to us being seen as opinionated, stubborn, dogmatic and confrontational. We may also struggle to understand another’s emotional needs, another key characteristic of forming and maintaining relationships, and can come across as unsupportive and insensitive. Given that we can have difficulties understanding what other people are thinking or feeling and why, many people with autism find it hard to adapt our behaviour relative to the situation or appreciate the effects that our own behaviour causes.

Are there any other characteristics of autism?

Many people on the spectrum have very rigid thought processes, thinking of the world in absolutes of black and white. We can therefore often have a love of routines, coupled with difficulties coping with change. People with autism will often structure their entire week to a rigid timetable in order to minimize the interference of unexpected occurrences, and can become agitated when this timetable changes. From experience, if I suddenly have to get something fixed on my car, somebody unexpectedly pops round for coffee, or the meeting I was intending to go to gets cancelled, it can throw my entire week into disorder. Of course, while many neurotypical people plan their weeks, it is the difficulty coping with the unexpected and unknown that makes routines significant for many of those with autism.

A large proportion of people with autism also have special interests or obsessions, normally involving facts and figures that can be memorized, common ones being animals and the natural world, or vehicles such as planes and trains. For example, as a child I could name every naval capital ship of World War II, the size and range of its armament, tonnage, thickness of armour, top speed, cruising speed, operational range, date of commission, and so on. However, a common feature of people with autism is that while we have excellent rote memory, we often have little genuine understanding, thus while I could list off reams of facts about naval ships, I could not tell you what they actually did during the war or what happened to them. I have met a man with autism who can list the architectural dimensions of every cathedral in Europe, but ask him about the purpose of cathedrals – religion – and he has no idea. The obsession can also focus on parts of larger wholes, such as the windows of buses rather than buses themselves, or lightbulbs rather than lighting fixtures.

Furthermore, many with autism have sensory issues, and so bright lights, sudden loud noises, certain tastes, colours, smells and textures can be intolerable to them. I detest the feel and flavours of many different foodstuffs so stick to a very small core of staple foods that I can eat without fuss. I have met many with autism who, like me, can hear like a bat and are highly resistant to pain. Many with autism can be claustrophobic in crowded places, and I am yet to meet someone on the spectrum who likes nightclubs. Furthermore, many of us suffer from clumsiness, finding it difficult to play sports or perform fine motor tasks such as tying shoelaces, and we can have a tendency to trip up or walk into things. If there were an award for tripping up kerbs, falling up stairs, banging your head on cupboard doors and walking into doorframes, I am sure that I would win it!

Does autism affect all people the same way?

It is common for people to generalize about autism, thinking one person on the spectrum is the same as all the others and treating all of us as having the same needs, strengths and weaknesses. Indeed, I have met many people who make assumptions about what I am like, my tastes and interests, and what I am capable of, based purely on the fact that I have autism – they normally think I’m great at mathematics or love doing Sudoku puzzles, for example. The truth, however, is that while we share a common condition, we did not cease to be individuals when we were diagnosed. When I first met a group of people on the spectrum, I was shocked by how different we all were. Some of us with autism are confident and outgoing while others are shy and withdrawn, some are friendly and welcoming while others are rude and antisocial, some playful and childlike, others serious and unemotional. How your autism affects you, how you adapt to it and cope with it, is individual to you.

Do all people with autism have special skills?

No! This is perhaps the most pernicious myth about autism – that we all have a miraculous, highly developed ability that compensates for our deficiencies, be it brilliance at mathematics, playing the piano or memorizing telephone books from a single glance. In reality, savant skills exist in approximately 1 out of every 200 people with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. These could be mathematical, artistic, musical or memory skills. I have met a couple of people who, upon being given a date anywhere in the last century, are able to say what day of the week it was without even thinking. These are, however, exceptions to the rule. While the vast majority of people with Asperger’s Syndrome or ASD Level 1 have intelligence that falls within the aver...