eBook - ePub

Yoga for Speech-Language Development

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Yoga for Speech-Language Development

About this book

Combining years of experience as certified speech-language pathologists and as qualified yoga teachers, the authors of this pioneering book explain how yoga can be used to aid speech-language development in children up to age 12.

The book includes a range of yoga-based exercises for improving pre-linguistic communication, vocabulary development and motor planning for speech. The text is enriched by illustrations of children in each yoga pose, so no prior experience of yoga is necessary to help children carry out each activity. The book also provides information on using this approach with children with neurodevelopmental and intellectual disabilities, including ADHD and autism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

INTRODUCTION

Chapter 1

YOGA AND ITS RELATION TO

SPEECH-LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

SPEECH-LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

Yoga, an ancient but perfect science, deals with the evolution of humanity. This evolution includes all aspects of one’s being, from bodily health to self-realization. Yoga means union—the union of body with consciousness and consciousness with the soul. Yoga cultivates the ways of maintaining a balanced attitude in day-to-day life and endows skill in the performance of one’s actions.

B.K.S. Iyengar

Introduction to yoga

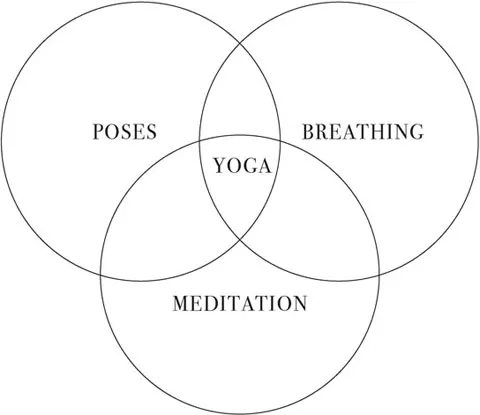

The word yoga comes from the Sanskrit word “yuj ” meaning to yoke or bind. Yoga is the union of the body, mind, and spirit. Since yoga was initially passed down from teacher to student by oral tradition, the exact origin of yoga in ancient India is unknown. Approximately 2000 years ago (Goldberg 2013), the great sage Patanjali systematized the philosophy and practice of yoga. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (Satchidananda 2011) contain insights for achieving this union of the mind, body, and spirit. This work describes the eight limbs or steps of yoga, which provide guidelines for living a full, purposeful, content life. Three of these practices—the poses, breathing exercises, and meditation—comprise the main parts of yoga, which are represented in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Three main parts of yoga: poses, breathing, and meditation

Yoga poses

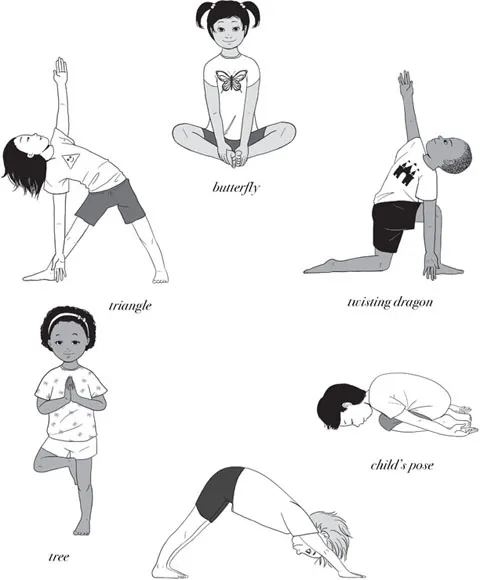

The first component of yoga, the physical poses, improves overall strength, flexibility, and balance. Yoga poses can be categorized as standing, balancing, twisting, hip opening, bending, and inverting. Figure 1.2 illustrates these six categories of poses.

Figure 1.2 Six categories of yoga poses: standing, balancing, twisting, hip opening, bending, and inverting

Standing poses, such as triangle pose, teach proper alignment of the body and feet, improving posture. Standing poses also ground and connect practitioners to the earth. Balancing poses, such as tree pose, tone muscles, elongate the spine, and improve body posture too. These poses require significant concentration, which help keep the mind focused in the present moment. Twisting poses, such as twisting dragon, release tension and lengthen the spine, increase shoulder and hip mobility, and stretch the back muscles. As the trunk of the body turns, twists activate kidney and abdominal organs to improve digestion and remove sluggishness in all the bodily systems. Hip opening poses, such as butterfly, promote proper alignment of the sacrum and pelvis so that practitioners can sit, walk, and move with greater comfort and ease. Hip opening poses alleviate stress, calm the nervous system, and combat fatigue. Hip openers are also important for practicing safe, deep forward and backward bends, as well as for sitting comfortably for meditation.

Forward bends, such as child’s pose, stretch the lower back and hamstrings, release tension in the upper body, and increase spinal flexibility. They also promote a calm, relaxed state. Backward bends, such as camel pose, open the chest and hips, strengthen the arms and shoulders, and increase the flexibility of the spine. Backward bends also stimulate the nervous system and clear the mind of extraneous thoughts. Inverted poses, such as downward facing dog, build strength and endurance in the upper body, as well as stimulate the brain. When the legs are positioned higher than the heart, the flow of blood and other fluids in the body reverses, relieving tension in the legs.

The different categories of yoga poses are not mutually exclusive as some of them can belong to more than one category. For example, “tree” is a standing, balancing, and hip opening pose. The ultimate goal of all the yoga poses is to prepare the body for stillness and meditation.

Yogic breathing

The second component of yoga, the breathing exercises, focuses on control over the breath. Certain breathing exercises calm the body, whereas others energize it. During a yoga practice it is important to synchronize the breath with the poses. For example, backward bending poses occur on inhalation, and forward bending poses occur on exhalation. Coordination of the breath with the yoga poses allows increased blood flow and oxygenation in the body (Williams 2010). A well-oxygenated body, and specifically brain, may positively impact overall learning.

In the west, hatha yoga is the most commonly known form of yoga. The word “ha” means sun, and “tha” means moon. Hatha yoga seeks to unite these opposite forces and find balance. Hatha yoga is the physical practice of the poses in conjunction with the breath. It involves safely challenging the body in poses while keeping the breath steady to find the balance between effort and ease. Proper alignment of the parts of the body opens the energy channels, especially the main energy channel in the spine. This results in a strong, flexible, balanced body, which leads to a balanced mind.

Yogic meditation

During meditation, the third component of yoga, the focus shifts from the distractions of the external world to the silence of the inner one. Concentration is the beginning of meditation. Concentration on an “object,” such as a sound, candle flame, or picture, can provide a single point of focus to begin meditation. Another path to meditation is the practice of “mindfulness,” which involves the nonjudgmental observation of thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and the surrounding environment from moment to moment (Alkalay 2001). Originally an ancient Buddhist tradition, mindfulness has become a popular contemporary subject of investigation and discussion, especially in the field of psychology. In 1979, researcher and leader in the area of mindfulness, Jon Kabat-Zinn, introduced his Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Since then, numerous studies have documented the physical and mental benefits of MBSR and mindfulness in general. The National Scientific Council of the Developing Child states that excessive stress damages children’s developing brain, which leaves them susceptible to learning, behavior, and health issues. Fortunately, evidence is building that the mindfulness practice present in yoga is an effective way to promote healthy brain development and function, as well as stress relief (Flynn 2013; Flynn and Ebert 2013). Current research also shows that teaching mindfulness in the classroom reduces aggression and other challenging behaviors while increasing calmness and concentration. Furthermore, scientific research indicates that mindfulness practice increases the density of gray matter in brain areas linked to learning, memory, emotion regulation, and empathy (Greater Good Science Center, University of California, Berkeley n.d.).

In summary, yoga strengthens the connection between the body, mind, and spirit. With a strong, flexible body and balanced mind, the practitioner connects to the inner spirit. Additionally, through a consistent yoga practice involving all three components—poses, breathwork, and meditation—the practitioner creates space for acquiring new ideas.

Yoga and speech-language development

Contemporary interest in and research on yoga has increased in recent years. The fields of medicine, education, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and psychotherapy embraced yoga, which is recognized by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) as a complementary, integrative treatment method. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) of the NIH provides a list of selected references on this topic.

The benefits of yoga for adults are documented in the scientific literature (e.g. Broad 2012; Lee 2006; McCall 2007; Yurtkuran et al. 2007). Growing evidence suggests that, like adults, children benefit from practicing yoga. The emerging evidence-base for the benefits of yoga with children consists of systematic reviews (e.g. Birdee et al. 2009; Galantino, Galbavy, and Quinn 2008; Kaley-Isley et al. 2010; Serwacki and Cook-Cottone 2012), randomized controlled trials (e.g. Jensen and Kenny 2004; White 2012), pretest-posttest efficacy studies (e.g. Eggleston 2015; Koenig, Buckley-Reen, and Garg 2012), feasibility studies (e.g. Thygeson et al. 2010), descriptive research (e.g. Harper 2010; White 2012), and anecdotal reports (Flynn and Ebert 2013). This literature suggests that yoga benefits children with respect to psycho-physiological outcomes, such as stress reduction (Eggleston 2015; White 2012), as well as increased self-regulation (Ehleringer 2010; Kenny 2002), attention (Ehleringer 2010; Jensen and Kenny 2004), and self-esteem (Eggleston 2015). Research has documented the educational and therapeutic benefits from the fields of education, physical therapy, occupational therapy, medicine, and psychotherapy. Some studies claim that children who received yoga as a rehabilitative adjunct to traditional physical (Galantino et al. 2008) and occupational (Koenig et al. 2012) therapies benefitted from the practice. However, researchers, including those who have conducted systematic reviews of the evidence, agree that additional research is needed. More rigorous research designs with larger clinical trials are required to support the use of yoga with both typically developing and disordered populations of children.

The practice of yoga in school settings has become increasingly popular over the past decade with an accumulation of the scientific evidence for this trend. When yoga is used in schools, the focus is typically on educating the whole child and includes areas such as improving test anxiety, stress resilience, concentration, well-being, and self-esteem (Butzer et al. 2015; Eggleston 2015; Flynn and Ebert 2013). Several manualized, research-based programs for elementary school children have been developed and evaluated in recent years. For example, evaluation of the Yoga 4 Schools® program (Hyde 2012) indicated that through their participation in this program, typically developing elementary school students improved their self-esteem, physical health, and academic performance. For another example, evaluation of the Get Ready to Learn program, which targeted challenging behaviors in students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Koenig et al. 2012), indicated that those students who participated in this yoga program reduced their irritability, social withdrawal, hyperactivity, and noncompliance.

In addition to yoga for the school-age years, programs have been developed for the infant-toddler and preschool populations. Baby Om and ChildLight Yoga are two examples of such programs. Children at these younger ages are in the peak speech-language learning years. It is our position that yoga practices for these age groups can support speech-language development.

As speech-language pathologists, we have noted that yogic principles and practices have been used to treat the speech disorder of stuttering (Balakrishnan 2009; Boyle 2011; Kauffman et al. 2010). It is also common practice in voice therapy to incorporate breath control (Gilman 2014) and vocal relaxation techniques, which are used in yoga. However, beyond stuttering and voice disorders, applications of yoga in the field of speech-language pathology have been limited. We acknowledge that the research to support the evidence-base for the direct use of yoga to enhance speech-language development has not been conducted. However, we firmly believe that the connections between certain yoga practices and speech-language and play development are sufficiently compelling.

This book addresses the logical relations between yoga and child speech-language development in different domains and at various stages. We propose that yoga can enhance speech, language, cognition, and play skills throughout the developmental periods. Yoga can enhance the prelinguistic communication skills of eye gaze, joint attention, and turn-taking in infants and toddlers. These skills, which reflect the children’s engagement with their caretakers, are the foundation for future communicative interactions. For example, turn-taking with vocalizations and toys during the first two years of life is the foundation for conversational turn-taking at later stages of development. The parent-child yoga classes for infants and toddlers provide many opportunities for engagement and prelinguistic communication.

The prelinguistic stage is followed by the emergence of early speech and language. Speech refers to the sounds emitted through the oral and nasal cavities and takes shape in the form of words (Hamaguchi 2010). Yoga, with its emphasis on the coordination of breath with movement, can enhance breath support for speech. Breath support involves stabilizing the body for proper airflow. Practicing the yoga poses helps stabilize the body. With the body strong in proper alignment, speech, which occurs on exhaled air, becomes more efficient.

Yoga can facilitate the motor act of speaking. The brain sends signals to the muscles that control the articulators, namely the tongue, lips, and jaw, to produce clear, connected speech. Two yoga practices, the poses and chanting (sound sequences), require motor planning, or praxis. The poses require motor planning at the level of the body while chanting involves motor planning for speech. Sequencing movements for speech is important for generating meaningful spoken language. Repetition of the poses and chants provides opportunities for children to practice and eventually master these different motor plans.

Yoga can help children build their vocabulary and linguistic concepts. By five years of age children understand at least 10,000 words and use at least 900–2000 words (Shipley and McAfee 2009). Yoga exposes children to different types of words including nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and prepositions. Many of these w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Disclaimer

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: Yoga for Different Developmental Domains

- Part III: Appendices of Yoga Resources

- References

- Index

- Join Our Mailing List

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Of Related Interest

- Endorsements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Yoga for Speech-Language Development by Susan E. Longtin, Jessica A. Fitzpatrick, Michelle Mozes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Audiology & Speech Pathology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.