![]()

PART I

THEORY

![]()

1

OUR UNDERSTANDING

OF AUTISM

Based on our working experience with people with autism and a lot of research, we have developed a comprehensive framework for understanding autism and the differences between people with autism and people who are not autistic. As a result, we often hear our clients say that they ‘finally feel understood and are able to be themselves’ during our conversations.

We may want to take it for granted that clients feel understood within a therapeutic context, but for people with autism this is frequently not the case. Therapists, counsellors and other professions may reach out to them with the best of intentions, but they rely on a set of standards that do not fit for people with autism. In other words, because professionals depend on a (non-autistic) worldview and on (non-autistic) ideas about the needs of people, they often intervene in a way that is not adapted to the specific needs of people with autism. We have learned that this way of working is not effective. If you want to work successfully with people with autism, it is crucial to understand how these people live, think and respond to experience.

For example, we noticed that social workers, parents or partners of people with autism are often concerned that people with autism may be socially isolated because they appear to have so few friends. If, however, somebody with autism feels perfectly happy with just one close friend and a few contacts on social media, who are we to judge that this cannot be sufficient for a good and meaningful life?

Furthermore, studies indicate that people tend to find more and better help in therapy or assistance when they feel understood, and it goes without saying that this applies to people with autism as well. This is why we find it necessary to share our understanding of autism, how we relate to our clients and their contexts to this particular framework, and how we work with them accordingly. We believe this is very important because our experience has revealed that autistic as well as non-autistic people find it difficult to comprehend what autism really means, what makes people with autism different and what this entails for their daily life and relations.

THE ESSENCE OF ‘BEING DIFFERENT’: THINKING IN DETAIL

The core manner in which people with autism differ from others is in how they think and perceive the world. Their way of taking in information, of using their senses as well as a specific way of processing these stimuli (by thinking), is different. People with autism see, hear, feel, smell, taste and use their senses in a manner that focuses a tremendous amount of detail, and their thinking is based on these details. The consequences of this should not be underestimated: imagine seeing your whole world in details, feeling and experiencing nothing but detailed information, and thinking accordingly!

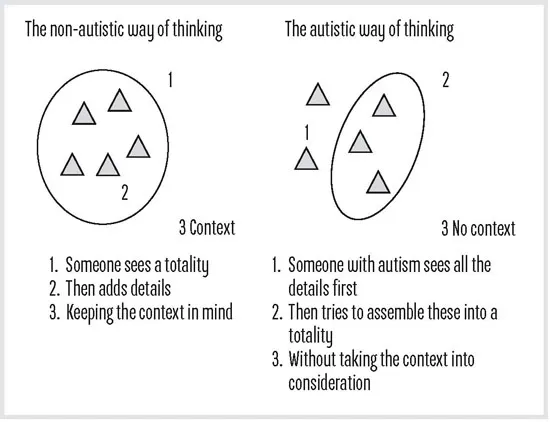

In an attempt to explain to our clients with autism and the people close to them how this detailed thinking works, we like to use the schematic drawing in Figure 1.1. Although it simplifies reality, it can help to get the picture of what it is that makes people with autism different.

Figure 1.1 Non-autistic/Autistic

Compared to those of us without autism, people with autism perceive things in a very fragmented way. They tend to focus mostly on details, and sometimes fail to see the bigger picture. If they do succeed in discerning a totality, it is because they see the sum of added-up details. Furthermore, it proves extremely difficult for them to take the context into consideration.

We believe this autistic way of thinking – experiencing their world in detail – is the base of everything that makes people with autism different from others. As a consequence, we notice it in the way they act, think, socialise, communicate and relate to others. We like to use the iceberg analogy. The biggest part, which is hidden under water and cannot be seen, represents the autistic way of thinking. Everything above the water in plain sight represents their utterances and is the result of this way of thinking – everything in the behaviour and thinking of autistic people that we tend to think of as different from what we regard as ‘normal’.

Because of the fact that this focus on detail is so basic to people with autism and so fundamentally different from the way non-autistic people perceive reality, we believe it to be crucial to see people with autism as being different.

In addition to this, we find it very important, and essential in our way of working, that we do not approach their problems by treating them as deficient or as having shortcomings. Their autism does leave them with certain limitations, but on the other hand it provides strengths and opportunities. What matters is that we discern these qualities.

Despite this vision, we are not blind to the limitations and problems people with autism struggle with in our society. It is absolutely important for a professional worker to have a clear idea of the exact nature of these limitations. This is what Part II is about.

AUTISTIC THINKING AS ANOTHER CULTURE

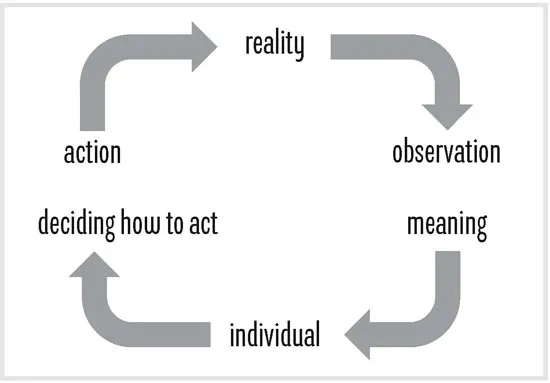

Because people with autism perceive the world in a completely different way, they give other meanings to what they see and experience. As a result, they will behave in ways that might seem ‘weird’ or strange to us. The connection between perception of reality, giving meaning and following behaviour can be pictured as in Figure 1.2.1

Figure 1.2 Coherence

People perceive reality with all of their senses. While ob-serving reality, the brain processes sensory stimuli. This process results in the giving of a meaning. Depending on our personality, history, context, previous experiences, values, ideas, etc. we give a certain meaning to certain stimuli or events. Based on our own thoughts, habits, experiences, etc., we assign meaning, and consequently opt for a specific action. Finally, we perform this action. This implies that meaning results in a certain choice of action, and thus in effective behaviour.

The reaction to these actions and their effect has in its turn an influence on the meaning we assign. It is a circular process in which thinking and acting have a never-ending mutual effect on each other. We see now that this process does not work in the same way with people with autism, but has a particular fashion of its own.

First of all, they experience and process sensory stimuli in a different way.2 In addition to the five external senses, there are two internal senses: a sense of equilibrium and proprioception (sense of position). The organs of balance detect rotating movements of the body in every direction. Because of that, they have a significant effect on our sense of balance and movement. The sensory cells responsible for our sense of position inform us about our posture and the movements every part of our body makes. Scientists have discovered that people with autism tend to react either over-sensitively or under-sensitively to some of these sensory stimuli.

J. always wears a backpack in which she keeps her sunglasses and her earplugs. She struggles with sunlight: it gives her headaches. Fluorescent light is unbearable to her. In places with a lot of noise, she feels compelled to use her earplugs. If she doesn’t, she gets overstimulated very quickly, and this results in physical pain. This overstimulation makes it necessary for her to leave. On the other hand, she fails to notice when she’s hungry (proprioception). She has learned to eat at fixed times. She doesn’t recognise the feeling of ‘hunger’.

C. is a 45-year-old woman. She knows how to drive a car and visits our therapeutic centre on her own. The road leads by a canal, which is lined with trees. Sunlight flashes through these trees when she passes them. That makes it very hard for her to drive that road. The sudden flashes are so intense for her that she has to stop halfway to calm herself down.

During training courses I like to use a projector for my presentations. Whenever M. accompanies me to speak from his experience, he cannot begin talking as long as the projector is working. That is because the machine produces a monotonous buzz, and M. is not able to ignore that noise.

J. is a very gifted man with autism. He cannot feel warmth, nor cold. As a result, he goes out on his bike in the middle of winter with nothing but a t-shirt on.

E. is an intelligent woman with autism, a teacher. She complains about headaches, especially in the evenings. After an exploratory conversation, it turns out that E. does not feel thirst. She forgets to drink during the day, and that causes her headaches. She concludes that she should drink a glass of water every time she takes a break. It turns out her headaches are as good as gone after that. But she now notices that she gets bad-tempered every Sunday, around eleven o’clock. She has no clue whatsoever why. Experience had taught me that people with autism often don’t feel hunger. She ponders this for a while, and decides to grab a bite halfway through the morning. It makes her mood a lot better on Sundays.

Olga Bogdashina states that there are many indications that autistic persons often have trouble dissociating sensory stimuli in the foreground from those in the background.3 They take them all in with the same amount of detail. Moreover, they experience each separate piece of information as a unit in itself. For them, a scene consists of a whole lot of separate particles that add up into that one scene. When one of those particles changes, the whole scene will be different.

A boy with autism goes on a school trip for the first time, and cannot use the toilet. It turns out that the toilet seats in the place they stay are old-fashioned black ones. But the boy only knows toilets with white seats. If it has a black seat, it is not a toilet to him…

Moreover, it became apparent that if there is too much information that needs to be processed simultaneously, people with autism are unable to divide that information into small meaningful pieces.

K. tells me that as a child he found it very difficult to recognise his class with his classmates each time somebody switched places. The classroom he knew consisted of that very room, with these same people on their fixed spots on the room. If places were traded, he considered it another class.

This example illustrates that people with autism give a different meaning to experiences, a meaning that people without autism often cannot understand. Therefore, people with autism respond to these experiences in a way that is likely to be found ‘weird’ or unusual by other people. But if you take the time to learn how people with autism give meaning to experiences, it turns out that their actions aren’t illogical at all.

They are just different.

We can compare this to people from different cultures. For example, if Greek people throw their heads backwards and simultaneously click their tongues very subtly, that means ‘no’. They move their heads sideways to indicate a ‘yes’. If you don’t know this when talking to a Greek person, there could definitely be a lot of confusion and misunderstanding.

If we have a conversation with somebody from a different culture, we are very much aware that they give different meanings to things. We ask for explan-ations, we make issues concrete to understand them better, and we adapt our own behaviour.

In the same way, if one wants to cooperate with somebody with autism, it is of the utmost importance that one gives enough thought to possible meanings they might attribute to experiences, stimuli and events.

AUTISTIC PEOPLE AND THE SOLUTION-FOCUSED APPROACH: A PERFECT MATCH

We try to maintain this basic attitude at all times, and with all of our clients. We approach our clients with an attitude of ‘not knowing’: we, the professionals, are not the ones who know what is best for them. Of course, we can make suggestions, but in...