![]()

———— Chapter 1 ————

Early Brain Development

and How We Learn

CHAPTER OBJECTIVE

This chapter will draw on our understanding of how young children learn and how repeated experiences, such as schematic behaviour, reinforce synapses.

Early brain development

Over recent years scientists have been finding out more and more about how the brain is formed and how it works. This is a fascinating topic and understanding how learning takes place enhances how we engage with very young children. This chapter will draw upon information about how our brains work and link it to schemas and learning.

The brain begins to develop very early in the womb at around three-and-a-half to four weeks when the unborn child develops the neural plate and the three main parts of the brain (forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain). After nine weeks, the unborn child’s brain has all its major structures in place, and can now begin to make connections between neurons, or brain cells. From this early stage, the brain controls reflexes such as the baby’s heartbeat, breathing, swallowing, sucking, and blood pressure. Although genes begin the process of brain development, it is the early environment and experiences of the child that now start to take over this process.

There has been a lot of debate about nature–nurture and whether we are born with certain dispositions and attitudes (nature) or whether we learn them as we grow and develop (nurture). We are born with certain genes that will affect us, for example, the colour of our eyes or skin. These things are inherited from our biological parents. However, our personality, attitudes and how we learn will depend largely on the things that we experience, the opportunities that we have and the environment in which we live. It is my view that both nature and nurture combine to develop us into the adults we become.

Certainly in terms of how our brain develops, it is sensory experiences that trigger the electrical activity necessary to enable the brain to develop connections and grow. These connections are called synapses.

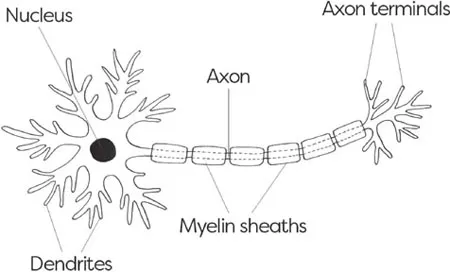

Figure 1.1 A neuron

We are born with a huge number of neurons; some estimates say well over 100 billion, which is more than the number of stars in the Milky Way. Each neuron has a long tentacle-like fibre called an axon. The neuron uses the axon to send messages to other neurons. The messages are sent as electrical signals and picked up by thousands of short, hair-like fibres called dendrites on other neurons. Each neuron has an axon and dendrites, so it can give and receive messages and is able to communicate with thousands of other neurons. Repeated experiences cause the connections to become well-worn pathways, and the repetition of an action or experience helps to etch these pathways into the brain. Once they have become strengthened sufficiently, they become permanent.

So let’s think a little bit about how neurons communicate with each other and how synapses are formed. I like to imagine that someone has walked through a grassy field that no one has walked through before. A pathway is made – we can see where the footsteps have pressed down the grass – but the pathway from A to B is not permanent. If we were to walk along that pathway through the field again and again, eventually the grass would disappear and a clear muddy path would emerge. Through repetition, this path would become permanent.

Using the term ‘connection’ for these pathways is technically a little misleading, because the neurons do not physically touch each other. There is a tiny gap that remains, across which the information can be shared through electrical impulses. This is usually referred to as a synaptic gap. Each neuron can potentially connect to thousands of other neurons, so our brains are made up of a huge network of synapses and neurons, like a dense forest of connections.

As information passes along the axon, a fatty substance called myelin builds up around the axon which acts like insulation allowing the information to transmit faster and more efficiently. The process of building up myelin is called myelination and occurs from the third trimester in the womb until adolescence, although myelin grows most rapidly within the early years. When we experience something from a very early age, myelin will grow and the more an experience is repeated, the more myelin a neuron produces. So repeated experiences not only allow the pathways in the brain to become stronger, but they also allow the brain to process information faster. Take, for example, a musician who needs to practise again and again to fine tune their skills until the process of playing a piece of music becomes internalised and they have gained mastery of their craft.1

Let’s think about what this means in terms of young children. It’s that moment when Sarah, a happy two-year-old, brings her key person the same book that she has already read many times that day and wants her key person to read it again! They groan, roll their eyes and try to direct her to a different book. But actually, reading the same book again is exactly what Sarah’s brain needs to make those connections and forge those links. She is learning through repeated experiences.

Or Charlie, the 18-month-old who drops his cup again and again and plays that game where we pick up the cup and give it back whereupon he immediately throws it to the floor again! (See Chapter 15.) This repeated behaviour, this trajectory schema (see Chapter 12), is actually all about learning. He is learning through repeated experiences.

It is also about Amiya who loves to sing and dance and requests the ‘turtle song’ again. It has been sung several times already during the session and the adults are beginning to find it tedious, but she is determined to sing it for the nth time! She is learning through repeated experiences.

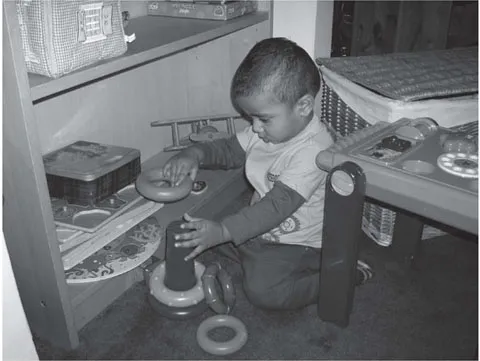

And it is also about Naresh (15 months) who is repeatedly taking rings off and putting them onto a post. He is thinking about which ring will fit next and using hand–eye coordination to manipulate the rings into the correct position to place them on the post. This play is schematic (see Chapter 8) and he is learning. He is learning through repeated experiences.

So the process of making connections is strengthened by repetition. Repetition helps the brain carry out its functions and is a foundation of learning, allowing more synapses to be formed and myelination to take place – repetition is how humans are hard-wired to learn.

Synapses are formed most rapidly within the first three years of life and it is during this stage that the brain is ready to learn many things that we take for granted. Young children learn to walk and talk in this phase and the brain has various ‘windows of opportunity’, as they are sometimes called, when it is primed to form new synapses and develop in certain ways. For example, for language it is generally accepted that the most sensitive period for learning is between the ages of one and three years old, which makes sense to me, since most children will learn to talk in this timeframe. Of course this does not mean that children (and adults) cannot learn outside of these so-called windows. Learning is a lifelong activity, with the brain potentially making connections until the day we die, although some theorists have noted that learning outside of the opportune times becomes more difficult and slower.2 3

The more we repeat an experience, practise a skill or do a particular action, the easier it becomes, until, for some experiences, we manage to complete the task automatically. If we think about our journey to work or a very familiar place, we travel this way so frequently that occasionally we can arrive and not actually remember the journey – it’s as if we were on autopilot! Then think about travelling to a new place – our brain will have to work much harder… We may need to get directions, write them down or print them and then pay extra attention to road signs or listen to our Sat Nav along the way. In this case, the neurons involved in navigating to this new destination have not shared synapses frequently before and so they communicate incompletely or inefficiently. This requires forming new connections within the brain, which results in greater conscious effort and attention on our part.

But the story of brain development does not end there. From an early age until late adolescence, the brain begins to prune away some of these connections. Those connections which are not sufficiently strong, have been neglected or are used infrequently are lost. Strong connections are exempt from this process. This is called synaptic pruning and the resulting brain has fewer synapses but becomes m...