![]()

PART I

THE FIRST

FORTY-NINE DAYS

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE PHYSICALITY OF ZEN PRACTICE

Meditation’s a mental business, right? That’s what I originally thought.

When I first came to Zen practice, more than 25 years ago, I had recently run a marathon and thought I was pretty fit. I arrived at the Soto Zen monastery and was duly instructed to fold myself into the cross-legged position and face a wall.

‘Just sit there,’ they said. ‘Relax. Don’t try to think or do anything.’

I was amazed. I had no idea how uncomfortable sitting still could be! My legs, my back, my shoulders – everywhere was tight. The whole experience was dominated by pain.

Somehow I stayed with it. I was taught some Zen yoga moves that helped my body to begin adapting.

In meditation, I did my best to stay present with these tight sensations. Over time the knots began to shift. My body adapted, and gradually I found my hips could open up, my shoulders could drop a little, my legs could release.

But as these areas opened, all kinds of memories, painful feelings and emotions came up. This physical and emotional release raged in my system for several years, and still continues somewhat.

Allowing this opening can, especially in the early stages, be a fearful thing to do. You really don’t know what you are going to meet, but you’re pretty sure it is not going to be pleasant. Is it worth going through this spiritual detox? Emphatically yes!

You may wonder if you have the courage to do this, but I can assure you that, if you really want to do this work, you can. Also, to a great degree, you can set the pace. If it’s all feeling too much, just scale back your practice by shortening your sitting period.

And all of this opening up comes simply from doing your best to sit upright, relaxed and grounded in your position.

In Soto Zen they have a saying: ‘Correct deportment is the Buddha dharma.’ Your physicality is considered that important.

The more you can transfer the elements of your sitting alignment into your daily life, from walking to the bus, to washing up, to lying in bed, the more rapidly this process of release can go on. Consequently, the more unburdened and free your life becomes.

We’ll come back to this detox process shortly, but first, let’s look at the practical aspects. How do you align your body for zazen, sitting Zen meditation practice?

ALIGNING YOUR BODY FOR ZEN PRACTICE

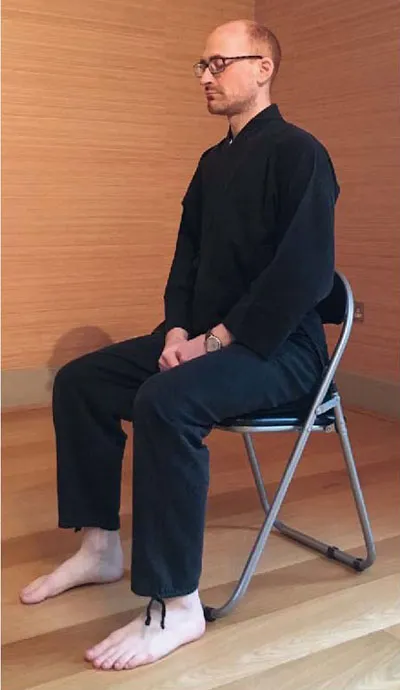

Even if you’re very flexible, start by sitting on an upright chair with a flat base, as shown in Figure 1.1. This allows you to concentrate on developing the relaxed uprightness of the upper body. What happens with your legs is secondary. We’ll look at other positions once we’ve got the essentials right.

Figure 1.1: Sitting on a chair

Don’t think that a chair is for inferior practitioners! The first Japanese Zen master resident in the USA, Sokei-an (1882–1945), had his students sit in chairs throughout his teaching career.

Settle the body. Ideally the hips are a little higher than the knees and the feet separated and flat on the floor. You may find it helpful to sit on a cushion to create something of a wedge shape beneath you. Your seat and your feet together give you the stability of a triangular base.

Just for a moment, sit on your hands and feel your ischia (sitting bones) – two projections that will press downwards. It is through these that your weight transfers downwards most efficiently. Now, move your hands to your lap, lengthen your spine and the back of your neck, and sway your body a little in all directions, gradually settling into the sweet spot where your body lifts up out of your ischia with minimal effort.

As you find this balance point, allow your body to become still. Relax your shoulders. Keep your neck long and your head balanced weightlessly. Find your chin placement by imagining you are holding a soft ball to your chest underneath your chin – your chin is tucked slightly but your throat remains open.

Look down the length of your nose with a soft gaze towards the floor in front of you. You can lower your eyelids to the half-open position, or you can allow them to softly close. Some Zen teachers are very insistent that the eyes must be open. Shinzan Rōshi never was. In my own experience I’d say there are certain areas in meditation that you’ll only ever explore with the eyes closed and certain areas that you’ll only ever explore with the eyes open. Over time it’s helpful to experience both.

Keep your mouth closed if you can, with the tongue broad and resting at the most comfortable place on the roof of your mouth. Allow your whole body to relax. Become aware of the rising and sinking of the natural breath, but maintain a gentle quality of muscle tone in your lower abdomen.

You are physically in the right place when you combine a sense of relaxation with balance and poise. Don’t worry if it takes some time to achieve this, just do your best. As long as you have a human body and mind, there will always be some physical niggles. If you have any physical disabilities, just do what you can to find ease and openness in your posture.

Initially you may find that you need to lean on the back of the chair, but don’t let this take you out of line and, if possible, gradually train yourself to sit upright without any support.

If you find it helpful to work with an audio commentary explaining what you’ve just read, you’ll find one online at www.zenways.org/practical-zen-online (the password is ‘insight’).

Some Zen practitioners claim that the whole of Zen is in the posture. For example, Suzuki Rōshi writes: ‘Enlightenment is not some good feeling or some particular state of mind. The state of mind that exists when you sit in the right posture is, itself, enlightenment.’

I’m sure that Suzuki Rōshi wasn’t a physical perfectionist, however. We work with where we are. I knew a fine Zen master who was born with a severe curvature of the spine. Daito (1235–1308), one of the greatest of the early Japanese Zen masters, had a crippled leg and could only assume a full cross-legged position on his deathbed. Many of us, too, are likely to do our most profound meditation on our deathbeds. At that point, I doubt our posture will be anything special. Nevertheless, considering zazen (Zen meditation practice) as a profoundly physical activity has some important ramifications.

I started planning this book at the beginning of the Chinese year of the dragon. The dragon is an interesting symbol shared by the Eastern and Western worlds, but we have a significant and important difference across our cultures in how we relate to it.

In England we think of Saint George going out to fight, conquer and ultimately kill the dragon. By contrast, a common image in East Asia is of sages or Zen masters actually riding on dragons. So what is going on here, and what does this difference tell us?

One way of understanding these images is to consider that they represent a difference in our attitude towards nature, and particularly the body. In the Eastern interpretation, the dragon represents the body’s life energy – a fierce and powerful force capable of exerting power over us. Here, in the Western world, particularly through the influence of Plato and the Greek schools of philosophy, the body is typically viewed as an animal or lesser thing that needs taming, and from which the spirit needs to find release. It is completely in accord with this view of physicality that a hero would go out and slay the dragon to bring about freedom.

But in Zen we don’t kill the dragon. We don’t kill anything. We learn how to come face-to-face with the dragon and with every part of our humanity. Sometimes this means looking into the dark.

You probably have areas within your history and your sense of self that are hard to face; perhaps there are regrets and shame. When we turn towards Zen practice and allow the consequent opening up to start, we begin to shine a light into all these dark corners. ‘Turning the light around’ was one of the ancient terms used for Zen practice.

Most of us have a long history of closing down or hiding these areas because life can then carry on in its regular routine with the illusion of safety. But if we just lock ourselves down, nothing is ever resolved. We become stuck.

It is true that what we find in the darkness may have a fearsome face, an evil dragon’s face; there are aspects of your being that are profoundly antisocial. You may find aggression and powerful hatred. You may find urges that would repel normal, polite society. But in your practice, you simply provide a safe space for these feelings to arise.

Of course, it’s important that you don’t act on these feelings and emotions. An important safeguard is the ethical framework of the Zen precepts. So what do we do when negativity arises?

This is easy to explain but not necessarily easy to do. The Zen term nari kiru, which can be translated as ‘become one with’, is helpful here. It means we utterly accept the reality of the present moment – all of it. Your awareness provides the safe place where these feelings can arise. You don’t hold on to them. You let the feelings come; you let them stay as long as they wish; you let them go. Let them come; let them go. When you’re doing this correctly, even very strong feelings might arise and nobody around you would necessarily know what was going on. Although these feelings and emotions aren’t suppressed, you aren’t investing in them or acting them out. You simply provide the space where they can release.

In doing this, you begin to realise just how much effort and energy it takes to hold all these tensions inside. And, as the feelings liberate, all their bound-up energy becomes available for use in your life.

As a Zen practitioner, your job is to allow this physical softening and release of feelings to happen continuously; but even while this is happening, you still deal with the responsibilities in your life. Whatever you need to do, whether it’s a business meeting with colleagues or playing with your children in the park, all this old stuff from the past just floats on through you. You let it all come – you let it go – let it come – let it go. That’s it.

In the Zen monastery, life is set up so you have to do this. There is no choice. For the first seven years of my own practice I, like everyone else, had six foot by three of living, sleeping and meditation space on a platform in the meditation hall, and was almost never alone. We each had to deal with anger, frustration, sorrow or whatever else arose, without it spilling out onto others. T...