![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

Home truths

I grew up in the south Wales valleys in the 1970s and, even though this was after the sexual revolution and the liberation movement of the 1960s, I was still surrounded by an odd mix of history and tradition. As I sat at my wooden desk in Brynmawr Board School in what was then known as the county of Gwent, my teacher Mr Fowler’s History lessons taught me that female activists such as Emmeline Pankhurst and Emily Davison had fought hard to gain social equality for women. Along with other members of WSPU (the Women’s Social and Political Union), they sought freedom from the restraints placed upon them by a patriarchal and reactionary society, one that was content to shackle women to the home and family, squashing their individual dreams and aspirations under piles of laundry and other household chores. My 10-year-old self was relieved to discover they had achieved success and it dawned on me that my mother’s right to vote, a benefit I would share in less than eight years’ time, and my own ability to enter the job market on an equal footing with my male classmates, was down in the first instance to the sacrifices made by women such as Davison and Pankhurst.

Tradition, on the other hand, taught me that even in the 1970s, women in Wales were often confined to the narrow sphere of the family home. Very few of my classmates had mothers who worked, especially while their children were young. Men laboured long demanding hours in heavy industry, such as in the steel works or in one of the many coal mines still operational before their gradual demise during the 1980s, but most of their wives found themselves confined to the home, forced to take satisfaction from a life of daily chores and child-rearing. Those women who were able to leave the house to work tended to have roles that conformed to the stereotypes of the time, and found part-time employment in lower-paid jobs such as hairdressers, cleaners or receptionists.

This difference between the genders was reflected further in the working men’s clubs and rugby clubs scattered throughout valley towns. Even in the very early nineties, when I was old enough to spend my weekends propping up the bars in such places, there were still rooms to which I was forbidden entrance. As a young woman I was welcome to sit in the bar and positively encouraged to part with my money, but certain side rooms remained strictly off-limits. They were as difficult to penetrate as the Pentagon, but only if you were a woman. These were shady, dingy poke holes filled with acrid smoke and the stale stench of beer. They were also the high courts of valley towns, where men repositioned the whole of the Welsh rugby team and scoffed and spat at the state of current politics. Such spaces allowed men the opportunity to indulge in the twentieth-century equivalent of a nineteenth-century phenomenon – male banter over a port and a cigar. Here was the chance to put the world to rights while enjoying an alcoholic beverage and the inhalation of nicotine confident in the knowledge that women had politely withdrawn to a more genteel room to idly gossip. Over a hundred years may have passed, but men still needed a space of their own away from the company of the women in their lives, rooms in which they felt free to swear, laugh, leer and moan.

One issue, however, continued to puzzle me. Whether playing on the rugby pitch or watching from the side-lines, men were lions. They roared, they stamped and they swore. They were the rough-cut kings of the turf and born leaders. But among the humdrum of everyday domestic life, it was the wives who not only made the rules but who also ensured they were implemented. Such women were just as likely to wave their rolling pins in the face of any miscreant husband as they were to use them to roll out pastry. While I was growing up I was left in little doubt as to which adult was really in charge in my own home or, indeed, in any of the houses of the friends I visited. Husbands may have been the ones who earned the highest weekly wage, but on pay-day it was their wives to whom many men mildly handed over the opaque packet containing a wad of five- and ten-pound notes and it was their wives who allocated the money on a needs-must basis. Payment for the rent man came first, followed by money for bills, shopping next, and if he was lucky any leftovers would be handed back to the husband as ‘drinking money’ for the weekend. This allocation of money was no easy task and debunks the perpetual myth of a ‘matriarchal Wales’ that has at times been projected through the media. Wives and mothers were strong because they needed to be, and because society and history has not always been on the side of the female. Women were often in the position of needing to prove themselves, even in the latter years of the twentieth century. And I know from personal experience and from watching my own mum completing such a creative task that juggling a weekly wage that has suddenly shrunk to a three-day wage due to factory cutbacks is never easy. Anyone who has ever had to do it deserves more credit than they will probably ever receive.

As a youngster I was often left perplexed by the odd mix of tradition and history that sat in such confusingly close proximity in most valley towns. The history I was taught at school seemed to suggest that women had freed themselves from the invisible bond of patriarchal control and had won the right to vote and seek gainful employment. Yet the tradition of the Welsh woman as I knew it suggested something different. Certainly she was a force to be reckoned with on the home front and ruled the life of her family with formidable strength, yet this in itself seemed to contradict the work of activists such as Pankhurst, Davison and other members of WSPU, who had surely envisaged for women a life beyond the home when they spoke with such passion for equality between the sexes. Without doubt the role of the typical ‘Welsh Mam’ had not been a consideration for the English suffrage movement, but it is an interesting one and certainly a role worth investigating when we consider the role of the suffrage movement in a specifically Welsh context.

However, when the early 1980s burgeoned into the late '80s, I was witness to a change in the behaviour of the women I looked up to and who I had known since childhood. As the years passed, women began to demand more and more from their lives. Valley women, my own mother included, began to expand their spheres, leave their homes and swap them for the workplace. They were no longer content with simply organising the lives of their own family members. They began to increase their confidence in their own skills and to see how easily they could adapt these to suit a career in the world of work. Little may have changed in the male-dominated rooms of the local clubs, but women were certainly finding their feet elsewhere.

I watched with pride as my mum went back to work for the first time since becoming a mother, a female cousin left the valleys for the excitement and adventure of an independent life in Sheffield, and my recently widowed grandmother found the confidence to gain employment in local government, having never worked since embarking on married life in the 1940s.

As I began to experiment with my own sense of style, my mum told me about the time she was 18 and had once shocked her neighbours by wearing a denim mini-skirt, white knee-high socks, and a t-shirt with the words ‘Virgo the Virgin’ emblazoned across the front. While some elderly gentlemen came out of their houses and shook their heads, my grandmother glowed with admiration at this seemingly small act of defiance. It gave her hope that her daughter was able to do what she herself had been forbidden when she was 18 – relishing the opportunity to be her own woman and confidently ignoring those individuals who wanted to mould every new generation of women into a model of compliance.

I was also faced with another important truth. Welsh women of my mum’s generation, those born in the 1940s and who reached the age of maturation in the 1960s, might have tended to put their families first, they might have been less-likely to be wage earners, or at least more likely to earn their income in a traditionally ‘female’ job, but that did not mean that while doing it they missed out on opportunities to remind society that they existed and that they had ambitions of their own to fulfil, even if they had to wait longer to actually go out and achieve this than their female descendants might have anticipated or hoped. While waiting for her chance to shine, my mother certainly made sure her neighbours were aware of her refusal to follow all of society’s expectations. She sent a gesture of defiance to the close-knit community of Blaenavon, a community still coming to terms with the possibility of female emancipation.

My mum Ruth wearing her over the knee socks and denim skirt. They caused quite a stir among her elderly neighbours!

These women from different generations, all of whom surrounded me when I grew up, play an important part in the wider sphere of Welsh social history. Although it is a part of local and social history that has tended to be marginalised, it is nevertheless possible to peel away fragments to reveal strands of inspiration for a generation of younger Welsh women. There is little doubt that the actions of these women are reflected by the many other women who, without applause or widespread recognition, influenced those looking for strength when trying to break away from the confines of expected behaviour. And although their names are not recognised by history, they play an important part in our understanding of the development of the suffrage movement in Wales. Without making a study of the everyday experiences of these women, it would be impossible to acknowledge how impactful the wider efforts of the suffrage movement has been on the lives of ordinary Welsh women.

One of the things I became disappointed with as a young student was the fact that, even in schools in Wales, the only Victorian and Edwardian suffragettes to appear on the History curriculum were English. No mention was ever made in my south Wales valley schools, either at primary level or comprehensive, of any Welsh women who fought for freedom from the margins of their home. No stories were ever told of a widespread and organised campaign of female suffrage. I gorged instead on the lives of the Pankhurst family, while secretly ashamed that Welsh women had apparently seemed so blasé when it came to fighting for their own right to vote. It wasn’t until many years later, when conducting my own research, that the names of such women as Elizabeth Andrews, Emily Phipps and Amy Dillwyn became familiar to me. But information about them is still lacking in a wider historical context when compared to the amount of material readily available about their English counterparts. Until relatively recently, many of them appeared to have been entirely forgotten figures with silent voices, marginalised figures apparently destined to dwell on the outer rim of mainstream political and social history. It is only because of the excellent research work of groups such as The Women’s Archive of Wales and individual writers with an interest in this topic, such as Swansea University’s Professor Kirsti Bohata, Ursula Masson and Deidre Beddoe that this issue is now being addressed.

Swansea suffragette Emily Phipps has also been confined to the footnotes of Welsh history yet, just like Elizabeth Andrews, she played a prominent role in the emancipation of women in Wales. In Swansea Municipal Secondary School, the establishment at which Phipps was headmistress, great emphasis was placed upon achievement, and encouraging students to take pride in their intellectual abilities. An anti-suffrage meeting held in Swansea, along with a desire to be a role-model for her female students, convinced Emily of the need to join the suffragettes and she became instrumental in setting up a local group. Her anger at the way suffragettes were being treated inspired her to become more militant in her actions, a belief that resulted in her participation in the 1911 Census boycott in protest at the refusal of the Liberal government, under the leadership of H.H. Asquith, to grant women the vote.

Women like the Rhondda-born campaigner Elizabeth Andrews, and Swansea suffragette Emily Phipps, have contributed far more to the act of women’s suffrage than history has so far been able to acknowledge. But in the year that marks the centenary of some women over the age of 30 being granted the right to vote, I hope that British women’s history as a whole will begin to show more awareness of the impact these individuals have had on the suffrage movement and that Welsh women can be given their rightful place in the pantheon of great female campaigners.

However, this book is intended to do more than simply resurrect forgotten names from the margins of social and political Welsh history. During the time of the suffrage movement there were women who, throughout Wales, were quietly but determinedly beginning to prove to themselves as well as to others that they could do more and be more than society had ever predicted possible. It is important that these women are remembered also, before history and time consign them to the forgotten wilderness of hearsay and legend.

During the research undertaken for this book, there were those who sighed and shrugged, believing that Welsh women had been apathetic when compared to English suffragettes in their demands for the vote. This is a travesty that history has perhaps yet to correct. The fight for equality in England was mainly led by middle-class women who had time and resources enough to fight. Many women in Wales were as eager for the vote as those in England, but the majority of working-class Welsh women from either the industrialised or often impoverished areas of both north and south Wales were also busy fighting for better conditions for their families and for their children. Furthermore, Welsh women in particular were still haunted by the treachery of the Blue Books.

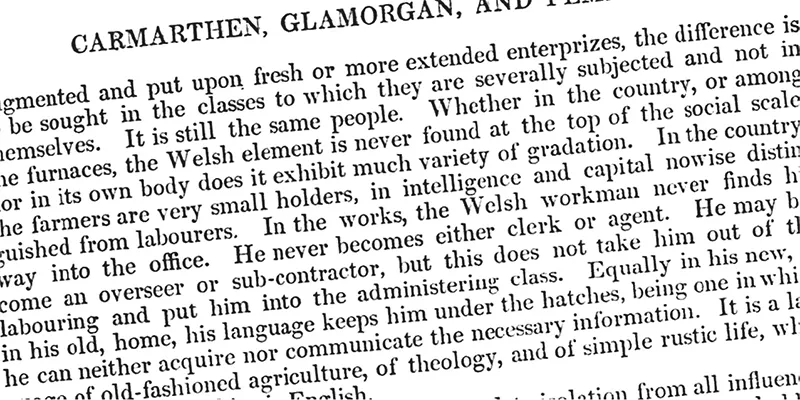

The Blue Books had been published in 1847 and were formally entitled Reports of the Commissioner of Enquiry into the State of Education in Wales. The commissioners who carried out the investigation were all English, their findings were scathing and naturally caused huge upset among the Welsh people. Their main gripe seemed to centre around the Welsh language, which they believed held children back in their education. But as the commissioners spoke no Welsh themselves, they relied upon the accounts of witnesses as part of their evidence gathering. The witnesses were mainly English speaking, Anglican members of the clergy. At the time much of north Wales in particular was non-conformist, so the ministers had their own axe to grind and were less than flattering, or truthful, in their thoughts. The report claimed that the education system was a failure because Welsh-speaking children did not understand their English-speaking teachers. But far worse was the damning critique given of the Welsh people themselves, in particular of Welsh women. Indeed, it was suggested in the report that whilst people as a whole in Wales were lazy, caring little for their spiritual welfare and general improvement, women were far worse, being generally flighty and flawed by moral turpitude.

Such an ill-informed report had a long-lasting legacy on the women of Wales, with many believing that if they behaved with aggression or violence during the fight for the vote, they would somehow prove that the lies contained in the Blue Books were true. This might go some way to explaining why the suffrage movement, with its non-violent stance, was more accepted in Wales. Women felt more comfortable fighting for the vote in a way that was unlikely to suggest they were either uncontrollable or, even worse, immoral.

An extract from the treacherous blue books.

The chapters in this book will therefore bring these local heroines to life, as well as reintroduce important names that are in danger of being forgotten. But before any of these women are brought out of the shadows, we need to begin with an understanding of what life was like for women in mid-nineteenth-century Wales.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

How black was my valley?

Everyday life for Welsh women in mid-nineteenth-century Wales

The women who lived in Wales in the 1850s were, in many ways, just like their English and Scottish counterparts. From a young age, girls were taught to see themselves as dependents, beings who could not think, interact or solve problems without the guidance of a typically patriarchal figure. This role firstly belonged to a young woman’s father and even in less well-to-do families, it was such male figures who controlled the movements of any unmarried daughters and, to a certain extent, any future plans they may have had. Although working-class women generally had more freedom to decide upon a husband than their middle- and upper-class contemporaries, there still existed the belief that the girl’s father had the ultimate decision on her choice of future husband. This could be seen no more clearly than in those Welsh communities that saw an influx of immigration, due mainly to employment opportunities in newly industrialised areas. Girls unfortunate enough to fall in love with a non-native of Wales ran the risk of ‘rhythus’, a ritual where a girl whose choice of future husband displeased the community was punished in a very specific way. Welsh men local to the area were allowed to urinate on her as a way of ‘bringing her to her senses’, and reinforcing the idea that ‘Welsh was best’.

The wealthier classes

In some ways life could be made easier if a woman was fortunate enough to belong to a certain social class. Those women born into the middle and upper classes could benefit from the advantages of money and, therefore, domestic and household support. However, this did nothing to change the way they were perceived by the family as a whole. They learned from an early age that the margins ...